Words: Nick Pigott

As the most powerful single-engine diesel locomotive in the world at the time, Kestrel promised a motive power revolution… but it turned out to be ‘too good for its own good’!

Shunned by BR despite its 125mph speed potential, it vanished behind the Iron Curtain where it became the rail equivalent of the Holy Grail, sparking ‘does it still exist?’ debates wherever railfans met. In the first of a two-part article to mark the 50th anniversary of its construction, The RM tells the extraordinary story of Brush prototype No. HS4000 Kestrel.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

It has been described by its admirers as the best-looking diesel locomotive to grace the railways of Britain… and even today it still holds the record as the mightiest in terms of brake horsepower.

But as has so often happened over the course of history, the most gifted don’t always enjoy the longest or happiest of lives and that was certainly the case with the 4,000hp prototype known as Kestrel. This great bird was capable of flying at 125mph and could soar to unprecedented heights as a heavy freight machine too, but its wings were clipped after just three years and it was packed off to the secretive Soviet Union, never to return.

What happened to it behind the Iron Curtain and the circumstances of its demise became one of the greatest ‘whodunnit’ mysteries of railway history and in the second part of this feature next month, we will be looking at the intriguing story of the Russian defector and its derivatives, using little-known information obtained from the former USSR. This month’s article sets the scene by examining the equally intriguing story of Kestrel’s time in the UK.

By 1965, BR was nearing the end of its steam cull and busily introducing the 3,000-strong fleet of main line diesel and electric locomotives it had ordered as a result of the 1955 Modernisation Plan. The largest main line class was the Brush Type 4 (later Class 47), designed by Brush Traction of Loughborough, with construction of its 512 members shared between that builder’s plant and BR’s Crewe Works.

Expansion

Most of the Brush 4s were fitted with Sulzer 12-cylinder in-line engines of 2,750 brake horsepower – a figure exceeded at the time only by English Electric’s 3,300bhp Type 5 ‘Deltics’ – and were ideal for mixed-traffic duties, so much so that BR in the early 1960s saw no reason for anything more powerful.

But rapid expansion of the UK motorway network coupled with a need to avoid inefficient double-heading for the increasing number of bulk freight trains caused attitudes to change and, in 1965, BR let manufacturers know that it would be interested in a mixed-traffic diesel-electric of between 4,000 and 5,000hp.

Within a year, English Electric had produced plans for a ‘Super Deltic’, rated at 4,400bhp. Housed in a bodyshell that would later be used for the Class 50s, it would have had a Co-Co wheel arrangement and two Napier T18-27K engines of 2,200hp each, yet weigh only 114 tons for an axle-loading of 19 tons. An alternative version with twin Sulzer engines would have been even more powerful, at 4,600bhp.

But in the true spirit of industrial competition, Brush Traction was also keen to win such a potentially lucrative order and had held a meeting with BR executives on July 21, 1965, at which it had gained the distinct impression that a twin-engine machine was unlikely to find favour, owing partly to high operating and maintenance costs.

The way was thus open for Brush engineers to steal a march on their EE rivals by offering BR a single-engine alternative, but in order to do so, they had to work with Swiss-based company Sulzer, which at the time was the only firm in the world capable of supplying a single power unit of that rating. Fortunately, Brush and Sulzer had a good professional relationship thanks to the Type 4 project and so it was agreed with BR that the Hawker Siddeley subsidiary would design and build a 4,000hp prototype weighing a maximum of 126 tons. Not only that, but the Loughborough-based firm – hopeful of winning British and foreign fleet orders – took the bold decision to bear the main financial risk as a private venture.

In return, BR undertook to collaborate closely on design and engineering, make technical and testing resources available, provide the loco with access to the national network and not stand in the way of overseas orders should any materialise.

In most magazines and books in the past, the credit for the design of Kestrel has been attributed almost exclusively to Brush and Sulzer, but official government documents kept secret under the 30-year rule and made available to the public by the National Archives for the first time in the year 2000 showed that BR was far more heavily involved in the specification of the loco than had been realised.

In fact, in a letter written to British Railways Board press officer, Eric Merrill, on August 9, 1965, BR chief traction and rolling stock engineer Mr J Harrison went as far as to state: “The design of this locomotive is virtually being controlled by us.”

Tradition

He added that it would “incorporate all the various features that we have found necessary in developing our own present-day diesel locomotives”, but he was careful to add that it would officially be known as a Brush product.

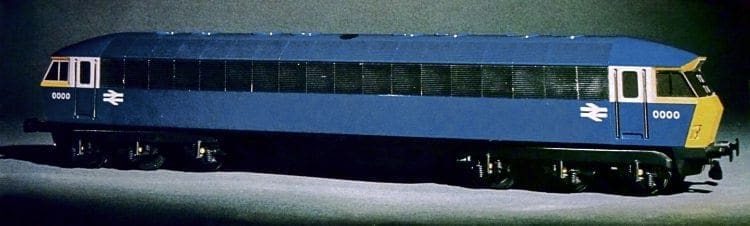

In keeping with its tradition of naming prototypes after birds of prey (Hawk, Falcon and a proposed Peregrine having been earlier examples), Brush decided to christen the project Kestrel and chose the running number HS4000, which was based on its nominal power rating and the initials of its parent company, Hawker Siddeley.

The experimental Sulzer 16-cylinder 16LVA24 V-type engine was actually rated at a maximum of only 3,946hp (at 1,050 revolutions per minute), but the company was able to justify the figure as 4,000 was the metric horsepower equivalent.

The all-welded bodyshell was an immensely strong stressed-steel monocoque design atop a Co-Co wheel arrangement, and the marriage of DC traction motors with an AC alternator for generation drew on experience the company had gained with Hawk (which it had rebuilt from ex-BR Bo-Bo No. 10800). The fitting to HS4000 of other AC components wherever possible and the use of a single power unit contributed to weight-saving over a twin-engined or 1Co-Co1 machine, of which BR already owned more than 390 examples, the heaviest weighing almost 140 tons.

Other differences between Kestrel and the Brush 4 design included semi-streamlined front-ends with swept-back windows and shrouded buffer shanks, giving an excitingly rakish and less functional appearance. To obtain such aerodynamic efficiency, Brush co-operated closely with the BR Design Panel and consultants Wilkes & Ashmore, culminating in a series of wind-tunnel tests made with the help of Malcolm Sayer, designer of the famous Jaguar E-Type car.

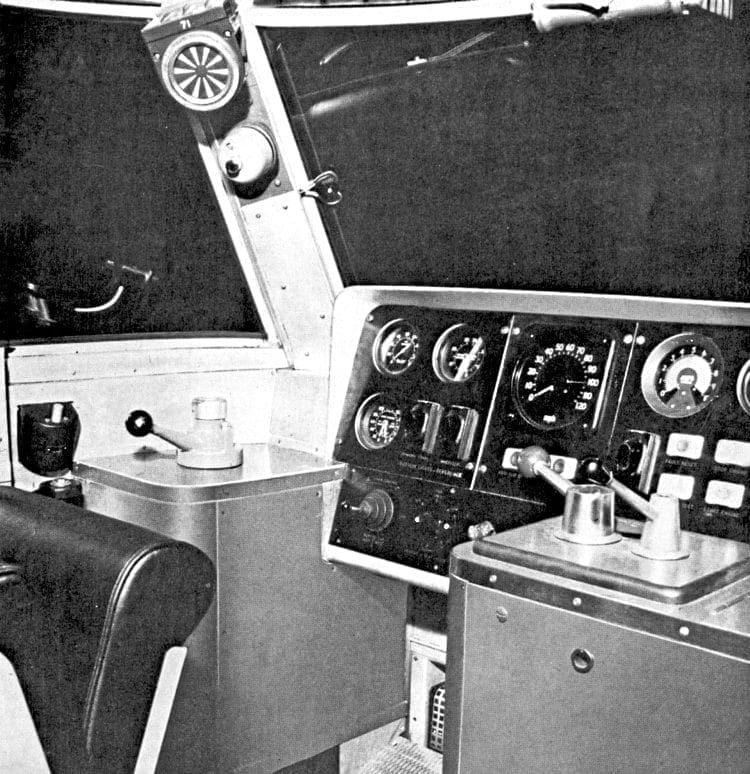

As a result, it was originally proposed to fit a futuristic bullet-shaped cab with a single driver’s position, but the fact that the loco was to be used for hauling freights as well as expresses led to a re-think and a more conventional twin-seat cab was selected. Crew comforts included a grill and small boiler in each cab plus a urinal and wash basin within the main part of the body.

Benefit

Preliminary preparations for the loco’s construction began at Brush’s Falcon Works in summer 1966 just as the Type 4 production line was beginning to wind down; in fact, final fitting-out took place in 1967 alongside that of the last two Loughborough-built Brush Type 4s, D1960 and D1961, both of which also benefited from AC generators. A few months earlier, five other non-standard Brush 4s (Nos. D1702-06) had been built with 2,650hp 12-cylinder versions of the LVA24 engine the prototype was to receive and those locos had been performing well in BR service.

In addition, the 16-cylinder version had successfully undergone 840 hours of static endurance testing before being installed in Kestrel.

The locomotive’s length over buffers was 66ft 6in with a bogie wheelbase of 14ft 11in and a total wheelbase of 51ft 8½in. Large cast-steel Commonwealth-style bogies contained wheels of 3ft 7in diameter, giving a maximum tractive effort of 70,000lbs and a continuous rating of 41,200lbs at 28mph (although in traffic, a rating as high as 85,900lbs was later to be recorded). The loco was designed so that a bogie exchange could easily adapt it for use on foreign railways of different track gauges. Automatic wheelslip-detection equipment was installed along with four types of braking system – vacuum, air, hydraulic and dynamic, the latter relatively new to British practice.

Construction of HS4000 (works number 711) was completed half a century ago in 1967 and it was tested within the Brush plant before being formally unveiled there on January 20, 1968, resplendent in a handsome and strikingly different livery of golden yellow and chocolate brown with a thin white waistline. The name was painted centrally on the bodysides and the number, plus the Hawker Siddeley name and logo, appeared in all four corners. This eye-catching colour scheme did much to accentuate the semi-streamlined profile and would do exactly what the company wanted it to… draw public attention and national media publicity to its new product.

Confident

Although Kestrel was not quite everything BR management had wished for in 1965, it was the most powerful single-engined unit in the world and arguably the most scientifically advanced that could be achieved with existing engine and electronic technology.

Brush’s management was confident in BR’s enthusiasm for such locos to speed up passenger services in the face of increasing competition from domestic airlines and to accelerate heavy freights to improve line capacity. Orders from Europe, North America and Australia were also anticipated, although not from developing countries, for whom such machines would be an expensive and unneeded luxury.

On January 22, 1968, Kestrel left Loughborough and ran light to Derby Works for weighing. This revealed a major problem that was to haunt the loco throughout its life despite the weight-saving measures mentioned earlier – for BR had stipulated a maximum tonnage of 126 but when the 1,000-gallon fuel tank was full, the total rose to 133 tons 6cwt. That was less than the Class 45 and 46 ‘Peaks’, but on two fewer axles, thus giving an average all-up axle-load of just over 22 tons.

Part of the reason for this was that a lot of prototype equipment of previously uncertain weight had been fitted, but despite misgivings, BR’s civil engineers gave limited permission for the locomotive to run to London via Cricklewood and Willesden depots and to make a loaded test trip from Marylebone station to Princes Risborough and return on January 27.

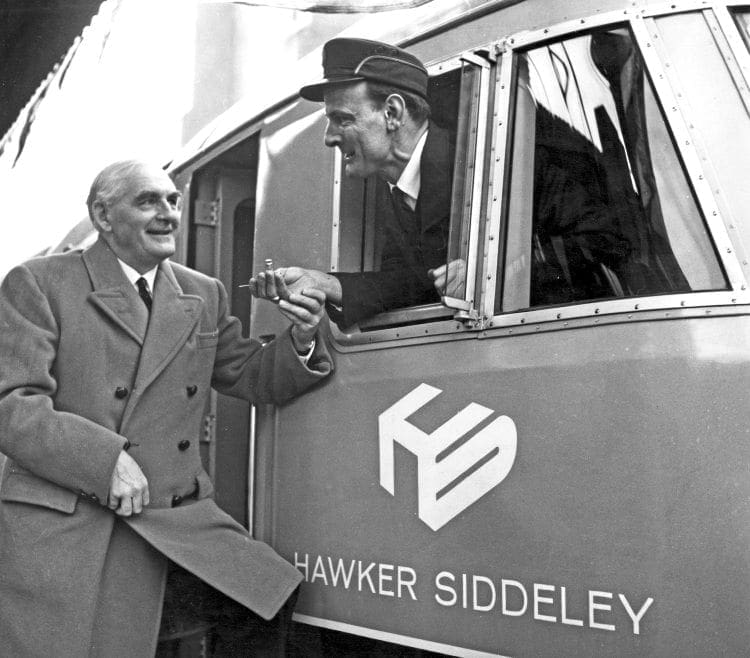

The official handing-over ceremony took place at Marylebone two days later when British Railways Board chairman, Sir Henry Johnson, formally accepted the loco on loan from Hawker Siddeley chairman, Sir Arnold Hall, and Brush Electrical Engineering Company chairman, Mr F H Wood, in front of BBC, ITN and Pathe News cameras. Among the VIP guests were the Australian High Commissioner, the director generals of the Spanish and Belgian State Railways, and representatives of Chinese, Indian, South African, Hungarian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Yugoslavian (and Russian!) state railways.

After ceremonially handing the master key to Derby-based driver Sid Gadsby, Sir Henry boarded the six-coach special and travelled to Princes Risborough and back with the guests and members of the media, who were presented with a 12-page colour brochure and a press release describing Kestrel as “the first AC/DC locomotive to work on BR”.

Among the many grand plans lined up for it was a high-profile event in early May to commemorate the 40th anniversary of nonstop running between King’s Cross and Edinburgh. These were to be in connection with the upcoming re-creation of that historic run on May 1 by LNER ‘A3’ No. 4472 Flying Scotsman and would have seen HS4000 haul the return leg south from Edinburgh to St Pancras via the scenic Waverley and Settle & Carlisle routes. In the event, the Gresley Pacific was left alone to enjoy the good publicity, for the prototype – which had returned to Falcon Works for modifications after its Marylebone launch – didn’t leave Loughborough again until May 6.

It had been expected to go to the Eastern Region for evaluation trials but instead was sent to the London Midland Region and ran light to Crewe Works. Although little had been done to lower the overall weight appreciably, it was allowed to travel light the next day along the North Wales Coast Line to Llandudno Junction on dynamic brake trials – but the day after that was the one on which it really showed what it was capable of.

Astonishing

A 670-ton Crewe-Carlisle test train comprising 20 Mk1 coaches was hauled almost effortlessly up the famous Shap bank and taken over the summit at no less than 46mph after losing just 14mph on the climb – an astonishing feat for a diesel. On a repeat run, the huge train was deliberately stopped on the incline and the immense power of the prototype succeeded in restarting it with no hint of wheelslip.

It should have been plain sailing for the project from that point, but in a cruel twist of fate, the loco’s introduction to traffic came at almost exactly the same time as BR imposed a 20-ton/100mph limit for all its expresses in a bid to protect tracks from the bruising effects of unsprung axle-hung traction motors – a decision taken partly in response to a tragedy at Hither Green in late-1967 in which 49 people had died as a result of a broken rail. Ordering Kestrel’s permitted maximum speed to be reduced from 90mph to 75, BR traction & rolling stock chief engineer, A E Robson, cited, “the effect of uneven and excess axle-load on switches and crossings”.

All of a sudden, it seemed, the British Rail enthusiasm that had encouraged Brush to build such a fast and powerful loco had evaporated for reasons beyond the manufacturer’s control.

However, even before that crash on the Southern Region, there had been indications at senior management level that BR’s zest for the project might be cooling. In a letter to Sir Arnold Hall as far back as autumn 1967, BRB chairman, Sir Stanley Raymond, had agreed to help Hawker Siddeley promote Kestrel overseas… but had pointedly refused to commit to any domestic orders.

“My difficulty,” he wrote, “will be in making clear that BR, although very interested in developments of this nature, is not in a position to indicate whether it will in future

be concerned with this particular locomotive. We are taking a hard look at our future locomotive requirements and the design specifications that may be involved.”

In diplomatic language terms, Sir Stanley was as close as he could get to washing his hands of Kestrel… and that was before the locomotive had even entered service.

This hard-nosed attitude was even more brusquely confirmed on December 7 that year when press officer Merrill wrote an internal memo stating: “It has been agreed that we will assist with publicity but that it must be made absolutely clear that we are not in any way committed to this particular locomotive.”

Blessing

A reason for this memo can be traced to a report Robson had presented to the Institution of Locomotive Engineers three months earlier when he’d revealed that mixed-traffic locos would no longer feature in BR’s future traction programme. Instead, it would be seeking a machine designed purely for heavy freight plus an express passenger version of up to 6,000hp.

Having given the Kestrel project its blessing at the outset, the nationalised company did, however, realise that it had a moral duty to Brush and despite the 1968 speed/weight imposition, agreed to honour its pledge to continue giving HS4000 access to the network. Until further notice, though, it would have to be restricted to non-passenger work only.

One proposal was to try it out on heavy oil trains from Fawley, in Hampshire, to the Birmingham suburb of Bromford Bridge, which were double-headed at that time. However, BR’s Eastern Region, to which HS4000 had been promised after its LMR trials, protested to the operations department at headquarters, pointing out that a programme of driver training on the Southern and Western Regions would be necessary.

There seems to have been a hint of possessiveness in the Eastern’s attitude (it had already tried to get Kestrel’s unveiling ceremony switched from Marylebone to King’s Cross), but BR’s chief operating officer agreed with its view on this occasion and the sophisticated new machine was consequently sent into the coalfields of central England to flex its muscles on heavy-haulage diagrams.

Allocated officially to the ER’s Tinsley depot in Sheffield but operating out of Shirebrook West shed, a few miles further south, it ran to the latter from Crewe on May 13, and after a brief period of driver training on the Shirebrook-Lincoln road, began hauling services between Nottinghamshire pits and Whitemoor marshalling yard, Cambridgeshire.

The average weight of those trains was 1,600 tons loaded – well within the loco’s capability as it was to prove during a major trial on August 7 when it hauled 52 loaded MGR hoppers of 2,028 tons gross between Mansfield and Lincoln – a train described by BR as the heaviest to be worked on its system by a single locomotive. (A similar claim had been made by the GWR for a Churchward 2-8-0 in 1906).

Apart from generating good publicity, the main purpose of that run was to test the loco’s ability to restart such a massive load on rising gradients, especially the 1-in-150 Boughton bank and the 1½ miles of 1-in-120 near High Marnham. From a standing start on the former in wet-rail conditions, the wheelslip-detection equipment worked perfectly and on the latter bank, Kestrel accelerated to 20mph in 6½ minutes and then maintained that speed until reaching easier gradients. Not only that, but the driver had to keep the controls in a low power notch in order to prevent the loco from breaking the 45mph speed limit for the wagons and route.

He would have been closely observed in that respect, for almost all the revolutionary machine’s trips in the early days had a Sulzer or Brush technical representative on the footplate in case of problems and part of their job was to keep a record of engine hours and mileage (something that continued to be logged until the very last days of the loco’s life in the UK).

On August 9, HS4000 was moved to BR’s research and development centre in Derby and while there made a number of 75mph trips in the Nuneaton area with West Coast AC electric loco No. E3132 coupled at the rear for test purposes.

By this time, the prototype had clocked up a remarkable 14,000 miles on coal trains despite being limited to a maximum of just 35mph, its workaday existence being relieved by exhibition appearances at Ratcliffe power station and Derby Loco Works, by 100mph trials in the Wilmslow area on July 21 and by test runs using an ex-LMS dynamometer car on a circular route from Derby and back via Stoke, Crewe, Nuneaton and Leicester, which continued into the late autumn.

Plodding

For those trials, BR relented temporarily on its speed restriction and the big bird managed at last to spread its wings, hitting 102mph – although that was still well within its design limit, of course. After a period of attention at Falcon Works, it returned to Shirebrook on November 22 to resume its humdrum life in colliery sidings and on the GN & GE Joint Line.

While it was plodding up and down this route twice a day, its colourful livery becoming increasingly grimy, Brush’s engineers were seeking ways in which BR could accept it into regular passenger service. The loco had already successfully come through bogie rotational tests on calibrated equipment at Darlington on May 23, 1968, but it was the excess weight that was the problem and so they decided to replace the big Commonwealth bogies with lighter ones of a type similar to those used on the Brush 4s, modified to incorporate hydraulic parking brakes. The two new components had a reduced wheelbase of 14ft 6in and were fitted between April and June 1969.

They had the effect of slightly reducing the locomotive’s power rating to 3,775bhp thanks to the use of Class 47-style traction motors but, more importantly, they brought the overall weight down to 124 tons 13cwt with a full fuel tank to give an axle-loading of 20.8 tons.

Although much reduced, that was still above the new 20-ton limit, but the difference was small enough for BR’s mechanical and civil engineering departments to make an exception and allow it to undergo driver-training on the East Coast Main Line in June and haul a six-coach test train from Doncaster to Peterborough and back on July 20, followed by a pledge to let it operate regular passenger services out of King’s Cross later in the year.

In the meantime, the loco continued its tedious freight existence, punctuated by open days at Crewe Works, Cricklewood and Barrow Hill that summer. At those, it was clear that its long period in the relative backwaters had not affected its star status as a darling of the enthusiast world and it was easily the most photographed modern traction exhibit on display. The railway press too was captivated by it and had featured it on the front covers of several magazines.

Superb

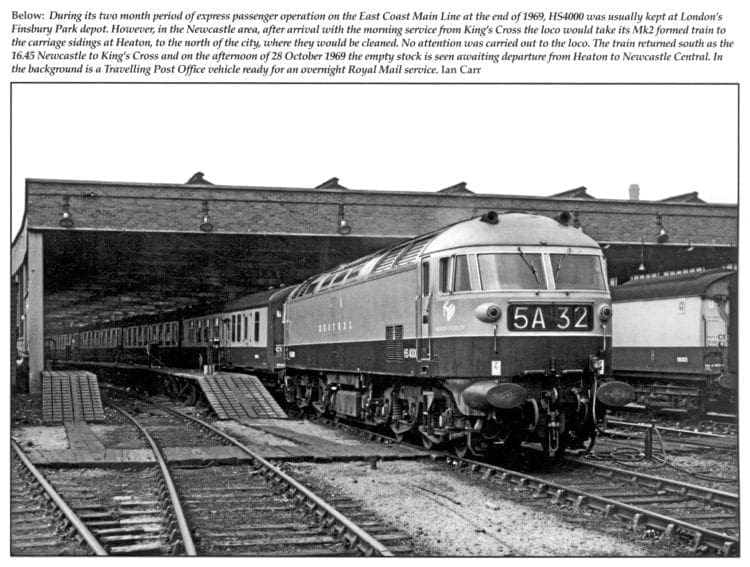

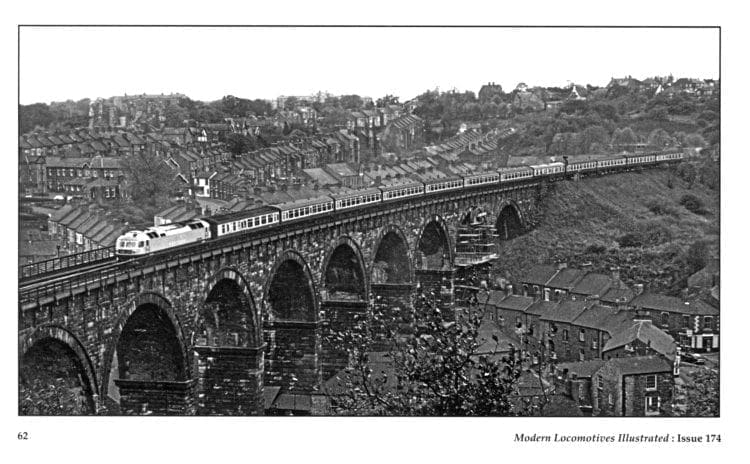

October proved to be the month the BR executives came good on their passenger train promise. On the 6th, Kestrel, which by then had accumulated a mileage of 67,615, was sent light engine from Tinsley to Finsbury Park depot – London home of the ‘Deltics’ – and after test and driver training runs to Peterborough and two brief visits to Stratford Works for the replacement of failed components, it was put in charge of the 07.55 King’s Cross-Newcastle inter-city service on October 20 and hauled it as far as York.

Performance on this first revenue-earning passenger service was superb with speeds of 100mph recorded on more than one occasion. The next day it worked a train back to the capital and again ran so well that on the 22nd, it was allowed to continue with the Down service all the way to Newcastle, returning in the afternoon on the 16.45 departure. So successful were those runs that on at least one occasion HS4000 reportedly knocked almost a quarter-of-an-hour off the normal ‘Deltic’ schedule.

It was also noted hauling Pullman expresses during that three-week period, but one of its most amazing recorded feats took place on November 10. On that day it was in charge of the 16.20 stopping train from King’s Cross to York with a load of 334½ tons. Technical difficulties meant that departure was 7½ minutes late, but all that lost time had been regained by the time the train left Huntingdon. Then, at Little Bytham on the ascent of the long and gruelling Stoke bank, south of Grantham, Kestrel managed to attain an astounding speed of 99mph! At that point, it was eased back, dropping to 93 at Corby Glen, but when full power was applied again, it once again began to accelerate up the incline and breasted that notorious summit at no less than 95mph.

Such a staggering feat would not be seen again, though, for despite its new bogies, this Hercules of a locomotive still weighed 13 tons more than the lightest version of Class 47 and a substantial 24 tons more than a ‘Deltic’ and the detrimental effect this was having on the track caused the BR civil engineers to reimpose a 75mph limit on it later that month. That caused Kestrel to be banned from the Newcastle and York diagrams and although some reports state that it continued on intermittent passenger duties until the new year, it was noted at Shirebrook again on November 25, once again eking out an existence on ponderous coal trains.

However, one of the conditions of the original trial-running agreement with British Rail was that the prototype could be demonstrated to potential overseas customers if necessary. Back in 1968, the German Federal Railway is understood to have expressed an interest and on March 6, 1969, members of a British/Soviet diesel delegation visiting Falcon Works had been shown the loco, which happened to be on site at the time.

That encounter had apparently come to nothing despite overtures to the Russians by Brush (see next month), but in December the same year, Brush arranged to entertain a group of visiting Australian engineers aboard the 08.40 York-King’s Cross passenger service on Monday the 22nd and BR lifted the speed restriction for just one day to allow Kestrel to haul it. The loco ran light to York on December 20 and the journey with the 12-coach, 396-ton train appears to have passed without incident, although nothing more was heard of the Antipodean interest.

Despair

By now, mileage had reached 86,472 with a high availability record of almost 90%, indicating excellent reliability, but the loco was due for works attention and so visited BR’s Doncaster Plant in January/February 1970 for engine removal and overhaul. It was duly returned to Shirebrook and resumed the old routine of running from Mansfield Concentration Sidings to Whitemoor with coal from collieries such as Clipstone, Thoresby, Mansfield, Rufford, Ollerton and Shirebrook.

The position at Brush was now one of despair. With its executives increasingly frustrated by the various restrictions and with the loco starting to become a drain on the firm’s finances, top-level talks with BR officials finally resulted in a change of heart. On March 9, Kestrel was taken off coal duties and sent to Hull for working Freightliner container trains between there and Stratford, east London.

Those faster freight services enabled it to stretch its legs considerably more, although photographs of it doing so are scarce, for the runs mainly took place at night, departing Hull at 19.35 and returning at 02.30. During the day, the loco usually received fuel and daily exams at Hull Dairycoates stabling point, only returning to Tinsley at weekends or whenever maintenance was required, although it was noted on Stratford shed on March 17.

An appearance as the star attraction at Crewe Electric Depot open day on April 19 again showed what a popular (and still relatively novel) attraction it was among Britain’s huge army of rail enthusiasts… the vast majority of whom had never seen it working in their neck of the woods, of course.

Sadly, the Freightliner duties were to be fairly short-lived, for power unit problems resulted in HS4000 being dispatched by Brush in late May and then to Vickers engineering works at Barrow-in-Furness, where it was to remain until early September. Even its journey there (hauled by Class 20 No. 8313) was fraught with problems, for it was reported that the London Midland Region refused to accept it beyond Mirfield because of its axle-weight and that it had to be turned back and sent to the coast of Furness via a different route.

Once the engine overhaul had been effected at Vickers under Sulzer engineers’ supervision, there was to be no more fresh scenery apart from another open day appearance at Barrow Hill and it was back to its old coal duties for the next seven months, meaning that the only depots this unique diesel ever spent any lengths of time at were Shirebrook, Tinsley and March, the latter being the maintenance depot serving Whitemoor yard.

It was while it was out of the public eye at Vickers that its fate in Britain was effectively sealed. For in 1970, BR chief engineer, Terry Miller, revealed in a presentation to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers that a fleet based on HS4000 was no longer the way forward and his view was confirmed in a document written by senior colleague Graham Calder. In that, he refers to the prototype still being “grossly overweight” despite its Class 47-pattern bogies and describes it as “overly sophisticated” owing to Brush having had to squeeze requirements for freight and passenger into one package.

“In my view, neither requirement has been adequately met,” wrote Mr Calder, adding that the over-crowding of equipment had also resulted in access problems for fitting staff, thereby making maintenance “difficult and expensive”. Bespoke new locos, he felt, could be designed and built at a greatly reduced overall cost.

Kestrel continued in coal train traffic until late-March/early-April 1971 and although its formal withdrawal from service does not appear to have been officially recorded, it is known to have been stored at Shirebrook for two or three weeks before being moved to Crewe Works on April 22. Its total mileage at withdrawal is usually quoted at 136,646 but there is some uncertainty concerning this as Brush engineers had ceased to log the exact mileage after January 29 with the figure at 122,756 and it is thought unlikely to have clocked up an additional 13,900 miles of unrecorded operation in a little over two months of weekday-only working.

At Crewe, it spent six weeks undergoing export modifications and then on June 7, with all its windows boarded up for safety, it was towed by Class 24 No. D5027 to Cardiff docks on Class 47 accommodation bogies, its 1968 Commonwealth originals having been regauged to 5ft (see Part 2 next month).

So how can the British life of Kestrel be summed up? The great bird was at least 10 years ahead of its time in terms of technology and ability, but Brush’s engineers were never able to see it working to its maximum potential, either at 125mph or in haulage terms, the latter partly because the gargantuan trains it was capable of handling (perhaps as heavy as 3,000 tons)

would have strained couplings and been too long for most of the UK’s goods loops. As for Sulzer’s engineers, they were disappointed that only five of their superb 16LVA24 engines

were ever built despite French State Railways showing interest at one stage. Three of those power units never even saw rail use, being installed as standby generators in continental power stations.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, HS4000 became the last diesel prototype to be built ‘on spec’ by a private firm for evaluation on BR with a view to winning fleet orders (although Brush did

risk collaborating with British Rail Engineering Ltd on the construction of the unique high-speed electric loco No. 89001 in the mid-1980s). Nevertheless, Kestrel was a magnificent example of engineering excellence and several aspects of its state-of-the-art technology were later incorporated in BR’s Class 56s, the contract for which was awarded to Brush in the early 1970s. The 56s even had an Iron Curtain link of their own insofar as assembly of the first 30 was sub-contracted to Electroputere, of Romania.

The Loughborough firm, which remained extremely proud of its 4,000hp protégé and even used it in publicity literature in the late-1980s, managed to recoup a further chunk of the Kestrel project costs by supplying traction equipment for the BR-built Class 58s and through worldwide electrical component sales until the time came for Falcon Works to begin producing complete diesel locos again with the Class 60s from 1989.

As with any prototype, HS4000 suffered from various snags, teething troubles and component failures during its career, but most of those were successfully rectified and even the weight problem could have been resolved with the removal of passenger-only equipment it didn’t eventually need, such as electric train-heating. The problem that proved insurmountable was a fundamental change of policy within British Rail itself.

For some time, partly as a result of the Hither Green broken rail tragedy in 1967, BR’s philosophy had been moving away from heavy machines with unsprung masses and towards what became the HST. This – coupled with the view that Kestrel was too sophisticated – eventually resulted in virtual abandonment of mixed-traffic development in favour of purpose-built freight locos and lightweight passenger sets featuring power cars at each end. The Advanced Passenger Train (APT) concept was also underway by then and BR’s national traction plan was gravitating towards greater homogenisation with the withdrawal of several non-standard diesel classes. Basically, the prototype fell foul of the fickle hands of fate and fashion.

However, as mentioned earlier, a Soviet delegation had visited Loughborough in 1969 and that event was to have far-reaching implications.

The striking appearance and stunning performance (potentially at least!) of Kestrel had made a big impression on the Russian visitors, especially the delegation’s leader, Dr N A Fufrianskii, a senior associate of the USSR’s Ministry of Communications. With Brush’s owners having given up on further progress with BR, the stage was set for an extraordinary new episode in the life of HS4000.

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 122 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter