Rail enthusiast or not, it would take a lot to miss all of the coverage in recent news about the celebratory anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon.

Fifty years on, the programme to take the first humans to the moon is arguably our single greatest achievement. At this time, half a century ago, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins would have been nearing the end of their journey back to Earth, landing in the North Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969.

Here are five things you perhaps didn’t know about the return leg of the Apollo 11 mission…

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Not everything came back

Not everything that went up to the moon was brought back. Items left on the lunar surface included equipment which had been carried up, stowed in the sample return containers and which were redundant after the moonwalk was over.

These included unused sample bags, two core tube bits, packing material and a spring scale for gaining some idea as to the weight of the samples, which were placed in the containers for return to Earth.

Other items included an armrest, lunar over-boots, a removable stowage compartment, plus some hand tools including scoop, tongs, an extension handle, a hammer and a gnomon (the part of a sundial which casts a shadow). This was all part of a weight reduction programme which had been planned well in advance.

Place your bets!

After the crew had a meal together, Mission Control read out a long list of news items, dominated by the flight, noting that the Russians had sent congratulations to President Richard Nixon and that this had been endorsed by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin.

They also reported that a boy in London had bet $5 on the certainty of a man landing on the Moon before 1970 and had already collected his winnings amounting to $24,000!

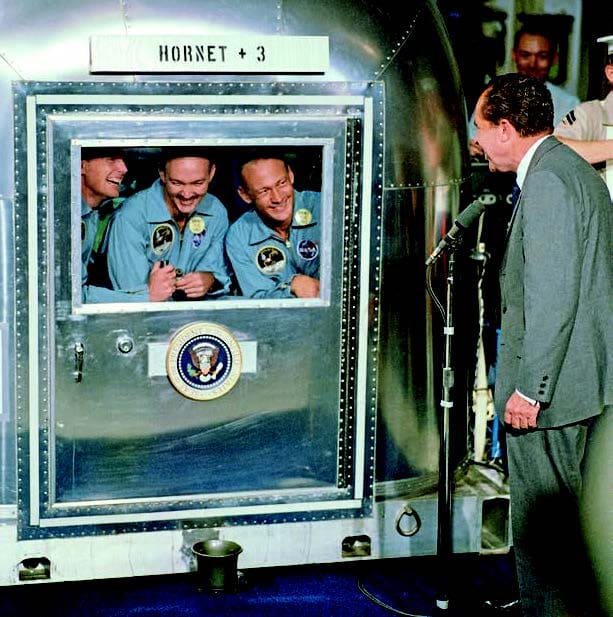

Quarantined

A period of isolation was required to prevent the release of any bacteria

picked up off the Moon. All three crew members were put in a Mobile Quarantine Facility before a welcome by President Nixon. Flown to the Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston, they spent two weeks in isolation before the quarantine was lifted.

There were no bugs but the fear that there might be had granted all three some respite before a 45-day tour across the United States and 25 countries. None of them would ever be the same again – and neither would the world.

Storms threaten landing

Weather satellites were not yet common in 1969, but US Air Force Captain Hank Brandli had access to top-secret spy satellite images.

The captain realised that a storm front was headed for the Apollo recovery area. Poor visibility which could make locating the capsule, and strong upper level winds – which “would have ripped their parachutes to shreds” according to Brandli – posed a serious threat to the safety of the mission.

Brandli alerted Navy Captain Willard S Houston Jr., the commander of the Fleet Weather Center at Pearl Harbor, who had the required security clearance. On their recommendation, Rear Admiral Donald C Davis, commander of Manned Spaceflight Recovery Forces, Pacific, advised NASA to change the recovery area, to a new location 215 nautical miles (398km) north-east of the original landing area.

Tributes to the fallen

Commemorative medallions bearing the names of the three Apollo 1 astronauts who lost their lives in a launch pad fire, and two cosmonauts who also died in accidents, were left on the moon’s surface.

Also, a one-and-a-half inch silicon disk, containing micro miniature goodwill messages from 73 countries, and the names of congressional and NASA leaders, also stayed behind.

You can find out everything about the historic mission to land the very first man on the moon in the brand new Apollo 11 bookazine.