Late August saw the final regular workings of France’s most powerful diesel locomotives. Ben Jones looks back at their varied career.

AFTER the devastation of the Second World War, the railways of France recovered quickly during the 1950s.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Electrification was a priority, with most of the major routes radiating from Paris and much of the industrial north and east of the country going over to electric traction between the late-1940s and the late-1960s.

However, certain main lines and many cross-country routes were not included in SNCF’s immediate electrification plans, but unlike other countries, notably the USA and UK, France did not dash headlong into mass dieselisation in the 1950s.

Instead, a longer-term strategic policy saw diesel traction introduced gradually on lines where electrification was not envisaged, replacing life-expired steam locos and, particularly on rural routes, reducing costs through the widespread introduction of diesel railcars.

Where electrification was planned, particularly in the north and east, steam continued as the primary form of traction until the electrics were ready.

Thanks to the efforts of gifted engineers such as André Chapelon, the company was blessed with some extremely efficient and powerful steam locomotives for express passenger and fast freight work.

So effective were these machines that no diesel locomotives of the time could match their power output and they remained in front-line service on key routes such as Calais-Amiens-(Paris) and Paris-Belfort-Mulhouse well into the 1960s.

High power

However, even the legendary Chapelon Pacifics and the magnificent ‘241A’ and ‘241P’ 4-8-2s could not go on forever and, as diesel engine technology improved, SNCF began to investigate high-power diesels to haul heavy express trains on non-electrified main lines.

From 1964-66, four prototype locos were delivered to test the relative merits of hydraulic and electric transmission.

Schneider-SEMT built BB69001/002, a pair of four-axle, twin-engine diesel-hydraulics rated at 3,510hp, while Alsthom/SEMT opted for a C-C wheel arrangement and two SEMT-Pielstick V16 engines supplying 4,000hp to one large ‘monomotor’ traction motor to each bogie.

The prototypes were significantly more powerful than SNCF’s diesels, the largest of which – the A1A-A1A 68000s, introduced in 1963 – were equivalent to a British Type 4.

Experience with the prototypes led to an order for 92 six-axle diesel electrics, albeit with a single 3,550hp AGO four-stroke V16 power unit, rather than the twin-engine arrangement of CC70000.

However, Alsthom retained the monomotor bogies, which were common with many SNCF/Alsthom electric locos of the period.

Designated CC72000, the locos were delivered between December 20, 1967 and June 21, 1974, replacing less powerful diesels (often used in pairs) and, either directly or indirectly, ousting many of the remaining large steam locomotives in the process.

They were built at Alsthom’s Belfort works in eastern France and scattered across the country, initially on the main lines to Brittany in the north-west; Nantes to Bordeaux and Toulouse in the south-west; Lyon-Mulhouse; lines east of Lyon to Geneva, Annecy and Grenoble; and main routes such as Paris to Clermont-Ferrand.

A unique feature of the monomotor bogie design was the choice of two speed settings for freight or express passenger use – 85kph regime marchandises (RM) maximizing tractive effort for heavy freight and 140/160kph regime voyageurs (RV) for passenger duties.

Nos. CC72017 and CC72021-092 had a maximum speed of 160kph, compared to the 140kph of Nos. CC72001-016/018-020.

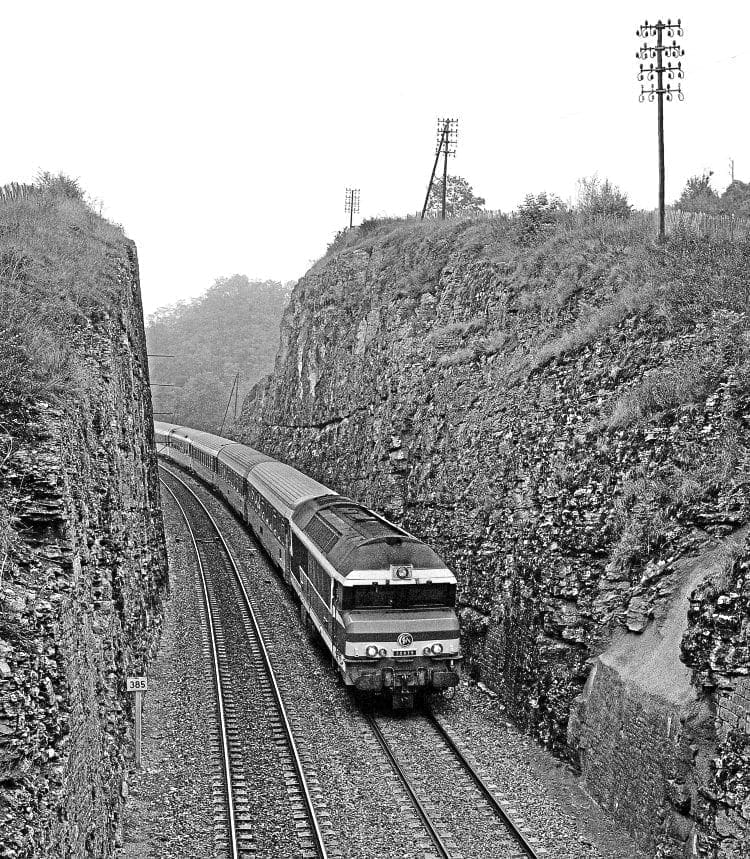

Like many other SNCF locos of the time, the striking outline and blue/white livery was the work of designer Paul Arzens.

The classic cab front design, nicknamed nez cassé (broken nose), not only looked superb, but gave additional collision protection for crews.

In their early years, duties included some famous international and domestic Rapide trains, including the ‘Catalan Talgo’ between Chambery and Grenoble, Trans Europe Express (TEE) ‘L’Arbalete’ from Paris Est to Basel (for Zürich) and ‘Jules Verne’ on the Paris-Nantes route, and the Bordeaux-Lyon-Grenoble ‘Ventadour’.

Disappeared

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, electrification spread further across the SNCF system, gradually eating into the express passenger work of the CC72000s and resulting in their transfer to new areas and, increasingly, to freight work.

By 1990, they had disappeared from Brittany and the Paris to Clermont route, taking over from the ‘68000/68500s’ and pairs of B-B diesels on the Paris Est-Mulhouse-Basel route (SNCF Ligne 4) and the cross-country Lyon-Tours-Nantes and Bordeaux-Clermont-Lyon routes.

Over the last 25 years, operations have steadily become more concentrated in the east of the country, but Ligne 4 would eventually become the route most closely associated with the class, providing diesel enthusiasts with almost five hours of fast main line running,

a rare experience in western Europe by the late-1990s.

Other lines that saw regular CC72000 action well into the 2000s included Dijon to Reims, Paris-Laon and Amiens-Calais. Between 1999 and 2005, Nos. CC72061/062/064 were fitted with Scharfenberg auto-couplers to haul TGV Atlantique sets between Nantes and the seaside town of Les Sables-d’Olonne.

Gretz-Armainvilliers, bound for Paris on July 24, 2008. BRUCE GALLOWAY

This expensive solution to the problem of providing a TGV link to the coast prevented the trio from working any other trains as their buffers were removed.

Freight duties took the class to many other destinations, not least of which was a diagram running from Stockem yard in Belgium to Metz via Luxembourg – a rare venture outside the borders of France.

Other well-known freight workings included steel coils to St-Chély-d’Apcher in the Auvergne region, running over Gustave Eiffel’s famous Garabit viaduct; mineral water trains from the Auvergne and Vosges mountains; and wagonload freight radiating from yards at Dijon Gevrey, Lyon Vénissieux, Saint-Pierre-des-Corps, in Tours; and various yards around Paris to destinations away from the electrified network.

From the late-1990s, the remaining 91 locos (No. CC72046 was written off after a colliding with a lorry at a level crossing in 1982) were split between Fret SNCF (61) and the Grandes Lignes passenger activity (30), based at Chalindrey and Nevers.

Freight locos were limited to 85kph in ‘RM’ mode. By now this was proving to be a handicap, and Fret SNCF increasingly favoured pairs of BB67400s with a maximum speed of 100kph and the insurance of two locos in case of failure.

Their decline was relatively swift, especially after Fret SNCF started to receive new BB75000 diesels from Alstom/Siemens in 2006. A steep drop in freight traffic also hastened their demise.

By the beginning of 2010, only four original CC72000s remained in traffic, including CC72084, restored to original 1970s condition in 2007 and destined to become part of SNCF’s museum fleet.

Nos. 72049 and 72074 are also still active with the AEF test agency, ostensibly for stock transfers, but they have been a regular sight on Paris-Troyes-Belfort trains during the final months of loco-hauled operation on Ligne 4.

New engines

In the early-2000s, the situation was somewhat healthier for the 30 Grand Lignes passenger machines, although they were increasingly unpopular due to their noisy and smoky power units.

Theye were banned by Swiss authorities from running through to Basel’s SNCF station in the early-2000s, and were also the subject of complaints from communities around depots and stations in Paris.

The solution was to modernise and re-engine the 30 locos (Nos. CC72021/030/037-041/043/045/047/048/051/056-60/066/068/072/075-080/082/086/089/090), installing cleaner, more fuel-efficient Pielstick V16 power units between 2002 and 2004.

After rebuilding, the 3,600hp locos became CC72100s by adding 100 to their original number. No. 72048 was the first to be treated at SNCF’s Quatre Mares workshops, near Rouen, emerging in August 2002.

While the new power units have done little to reduce noise levels, they were certainly cleaner than the original engines, at least over the first few years. CC72100s have dominated Ligne 4 operations since the early-2000s, although the importance of the route has steadily diminished over the last decade.

BEN JONES

The biggest blow came in 2011 when the LGV Rhine-Rhone high-speed line opened between Dijon and Mulhouse.

As a result, passengers between Paris, Belfort/Mulhouse and Switzerland were directed to faster TGVs and the loco-hauled service was cut back to Belfort and reduced in frequency. Since then, the status of Ligne 4 has slipped further with former inter-city trains becoming subsidised regional services to Troyes, Chalindrey or Belfort.

SNCF and France’s regional governments have invested billions of Euros in new multiple units over the last decade, often to the detriment of classic loco-hauled trains.

Work for the CC72100s has steadily declined over that period, with Paris Nord-Laon being lost at the end of 2006 and Nancy-Remiremont trains a year later.

Dijon-Reims TER diagrams were lost to bi-mode multiple units in December 2014. By 2016, the CC72100 fleet at Chalindrey had dropped to just 16 machines.

BRIAN STEPHENSON

The demise of CC72100s on Ligne 4 has been expected for some years, but the beginning of the end finally arrived in early-2017 when the first ‘Coradia Liner’ bi-mode inter-city multiple units were delivered by Alstom.

After tests, they were gradually filtered into traffic from February, replacing the classic CC72100 and Corail stock combination by April. The remaining two peak-hour Chalindrey-Paris Est diagrams ceased on August 28, although one set is expected to be held in reserve until the end of 2017.

Export versions

French train builders, particularly Alsthom/Alstom, have always been active in the export market and 14 close relatives of the CC72000s were built for ONCF in Morocco in 1969, designated DF100-114.

To supplement that fleet, ONCF bought six redundant CC72000s from Fret SNCF in 2006 (Nos. CC72003/009/018/020/027/085) and renumbered them DF115-120. The locos are used on freight and passenger work on non-electrified routes.

Portuguese Railways (CP) also took delivery of 30 diesels with a strong family resemblance to the CC72000s in 1981.

The 13 Class 1900s were built for heavy freight work and joined by 17, slightly faster, Class 1930s for passenger duties.

All were built in Portugal by Sorefame under licence from Alsthom. Although externally similar, they are less powerful than their French cousins and do not have monomotor bogies. CP’s locos are also ‘endangered’ in 2017, after electrification of their traditional routes and, most recently, the delivery of new Vossloh/Stadler ‘Euro4000’ diesels for CP’s

now-privatised cargo division.

Back in France, CC72084 continues to fly the flag for the class, and looks set to remain active for some years. Fret SNCF green/silver CC72029 is now part of the fleet at the superb Cite du Train museum in Mulhouse, close to the Swiss/German border.

Preservation group l’ARCET has restored No. CC72064 – one of the three locos formerly modified to haul TGVs – to 1980s condition with SNCF ‘noodle’ logos at Lyon Mouche depot.

Over a 50-year career, these powerful, imposing machines have proven to be worthy successors to the outstanding SNCF steam locomotives they replaced.

Their ability to run at up to 160kph with 500-tonne express trains or move heavy freights in difficult terrain has proved invaluable.

To borrow a term from professional cycling, appropriate in the land of the Tour de France, the CC72000s have amassed an impressive and fascinating palmarés that has made them extremely popular with enthusiasts in France and beyond, and should guarantee a prominent place in French railway history. ■

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 122 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.

Captions