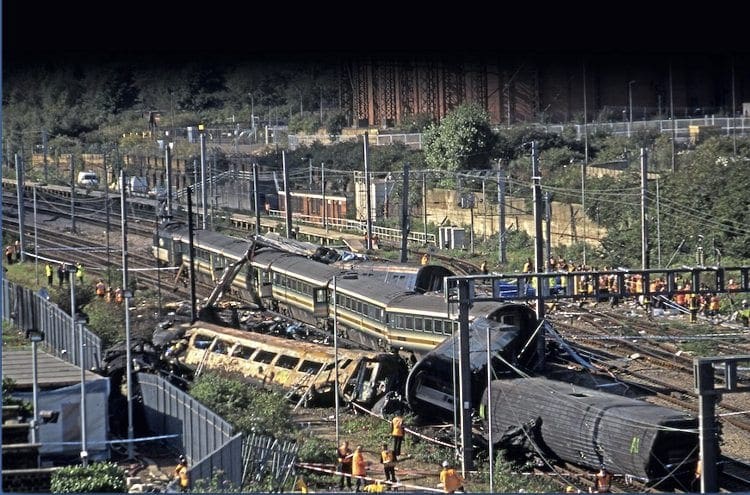

Thirty-one people lost their lives on Tuesday, October 5, 1999, when a Thames Trains Class 165 ‘Turbo’ collided with a First Great Western InterCity125 at a combined speed of 130mph at Ladbroke Grove, two miles from London Paddington.

Fraser Pithie and The Railway Magazine look back over 20 years to one of Britain’s worst post-Privatisation railway accidents, and considers the key factors which led to such a disaster and the step-change in safety that followed:

I want to begin by remembering the 31 people who lost their lives, the families and friends they left behind, and the considerable number of other people who were seriously injured as a result of the collision of two trains at Ladbroke Grove, London.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

None of us should forget that for the families and friends of those lost or seriously injured, every day of their life has been impacted. In recalling the events on the accident’s 20th anniversary, I do so with the utmost respect to the lives lost, the survivors and the memories and feelings of those affected.

The story of the tragic events of October 5, 1999, does not start on that date, but 10 years before, in 1989, when a scheme was approved by British Rail’s Board to modernise the track layout between Ladbroke Grove and London Paddington. The reasons for these changes were the needs of the increasingly successful InterCity main line and Network South-East services. Together with a proposed rail link with Heathrow Airport and a servicing depot for the Eurostar International service, there were several elements to consider.

As part of the plans, the permanent way was designed to operate at high running speeds. High-speed crossovers and connections were included with the intention of running speeds of 100mph just two miles from Paddington station, with some crossovers potentially operating at up to 90mph.

Assumptions

The track layout preceded Privatisation in 1994. When designed, it appeared assumptions were made that the layout could be safely signalled; the track layout was finalised without reference to the location of signals.

The section between London Paddington and Ladbroke Grove junction had six bi-directional lines. There were several crossovers to allow lines to be used in a flexible manner. At Ladbroke Grove junction there were connections between the lines.

To the west of the junction, there were four lines, being traditional Up (to London) main and relief lines and Down (from London) main and relief lines.

The lines were controlled by four-aspect colour light signalling, which was mostly mounted on gantries that spanned all of the tracks. The signals were prefixed SN, indicating ‘Slough New’, originating from the remodelling of the Paddington layout, which took place in the early 1990s.

The signals were controlled from the Integrated Electronic Control Centre, located at Slough.

The visibility of signals on Gantry 8 was affected by Portobello Bridge, which was a few hundred yards west of the M40 flyover at Westbourne Park. It was 100 years old, and carried the Golborne Road over the tracks using a large lattice construction with under-slung traverse girders. The bridge preceded Gantry 8, which accommodated the last Down (away from Paddington) signals, controlling movements primarily to the Down main and Down relief lines.

Original article can be found in the October issue of The Railway Magazine, click here to purchase a copy.