As one of Britain’s longest distance trains prepares for the arrival of new rolling stock, Ben Jones takes a trip on LNER’s ‘Highland Chieftain’ to experience the changing atmosphere onboard as it speeds north.

Eight hours, 580 miles, two countries, two sets of crews and a clientele ranging from muddy hikers to movie stars and royalty; LNER’s ‘Highland Chieftain’ is a unique operation for many reasons.

Named trains always feel special, but this one is much more than just the 12.00 off ‘The Cross’. It provides a vital connection between London, Edinburgh and the Highlands, a social and economic thread that supports cities, towns and villages along the route and supports a booming Scottish tourist industry.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Anglo-Scottish traffic has been vital to railway companies since the mid-19th century when the piecemeal construction of the two main lines to the North was completed and through trains started to operate. From the outset, railway companies competed fiercely for this lucrative business, transporting the aristocracy, wealthy families and their entourages to Scotland for hunting and fishing.

Comfort and speed were key to winning this traffic, and over the years both day and night trains became ever more luxurious, and heavier.

Flagship

Most famous of them all is the East Coast Main Line’s ‘Flying Scotsman’, which began in 1862 and is still one of LNER’s flagship trains. The ‘Chieftain’ is, by comparison, a mere toddler, having been launched by BR’s Inter-City sector in May 1984.

Over the decades, thanks to faster and more frequent trains, long-distance rail travel has become a somewhat more democratic affair, and while the tweed-clad aristocracy is no longer in evidence, trains to and from Scotland are busier than ever.

Today, LNER carries more than four million passengers a year on its Anglo-Scottish trains. On a hot Friday in mid-August, with the Edinburgh Festival in full swing, it feels like a high percentage of those are on our HST as it heads north!

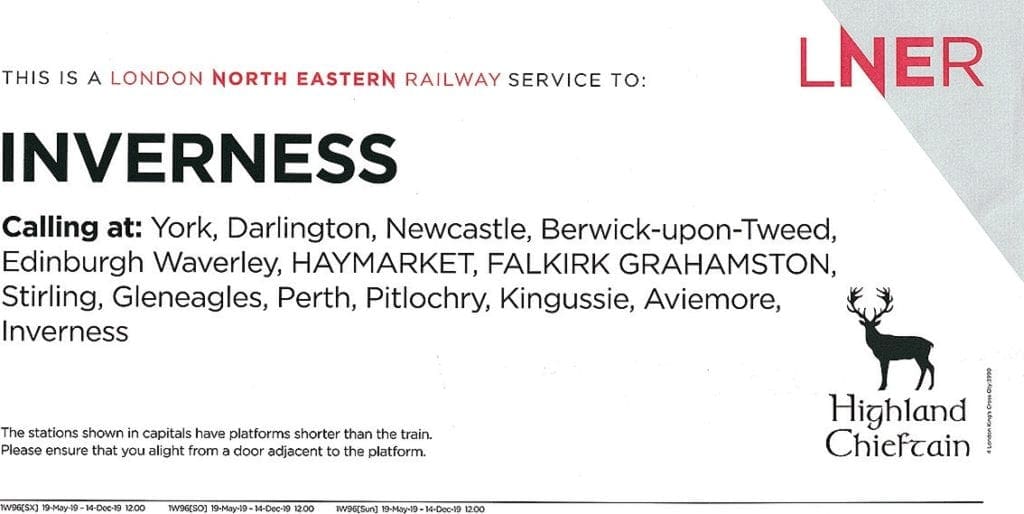

Walking across the concourse at King’s Cross, the changing face of LNER is illustrated by a sleek Class 800 ‘Azuma’ mingling with the familiar HSTs and InterCity 225 sets. Only the train information boards give any clue to the unique place of the 12.00 departure among the many other LNER trains heading north every day. Walking up to the country end of the platforms, I’m delighted to see that the leading power car today is No. 43308 – complete with Highland Chieftain nameplates. Its partner is No. 43309. Both are East Coast Main Line veterans dating from late 1978.

Right Away

As befits one of the fastest ECML trains, 1W96 (Whisky 96) is ‘right away York’, completing the first 188 miles in one hour and 52 minutes. Half an hour later, after racing through the flat expanse of the Vale of York, it’s Darlington and then, around 14.50, the HST slows to cross the King Edward Bridge, high above the Tyne, as it eases into Newcastle’s magnificent Central station.

The length of the journey and the need for a complete crew change gives the ‘Chieftain’ something of a split personality. At Newcastle, the English crew hands over to a Scottish team. Based in Inverness, this crew is dedicated to the ‘Chieftain’, working a 12-hour out-and-back turn each day punctuated by a short break in Newcastle.

Settled back into our seats after leaving Newcastle, the difference gradually becomes obvious; the new crew works its way through the train, greeting regular passengers and familiar faces with a relaxed style that comes with long experience.

Some of LNER’s ‘Chieftain’ staff have worked the train since it started – almost 40 years ago – while others are well past the 20-year milestone. George, today’s train manager, has been on this route for 20 years, while Katherine, one of the First Class hospitality team, is the ‘newbie’ at just two years!

A core team of 12 Inverness-based onboard staff work the trains, with Newcastle-based drivers on out-and-back turns and guards from Edinburgh. Such a close-knit team makes for a family feel, but like LNER train crews along the whole route, they are professional and committed to delivering excellent service.

As we speed towards Berwick and the border with Scotland, it’s time to walk through the train and get a feel for who is using it. This is easier said than done today thanks to the bags, rucksacks and suitcases stored in every possible space. The Edinburgh Festival and Fringe bring hundreds of thousands of visitors from across the world to the Scottish capital every summer, and we are right in the middle of that frantic period for the railway. Add to that the usual weekend traffic for a Friday afternoon, and summertime tourists heading beyond Edinburgh, and the importance of the ECML to Scotland becomes even more obvious.

Negotiating the obstacle course of Standard Class, it’s possible to overhear conversations in Japanese, Chinese, German and French, but also plenty of young Brits, Americans and Australians heading for the Festival Fringe. Back in First Class, it’s generally an older, wealthier clientele, heading home after a week’s business in London or destined for a holiday north of the border.

Intermission

Before we know it, we’re passing Craigentinny depot, home to the LNER HST fleet and soon to be populated by Hitachi bi-mode sets. As we slow for the Edinburgh stop, tablets, books and headphones are stuffed back into bags and suitcases are extracted from luggage racks as passengers gather in the vestibules, ready to disembark.

Four hours and 20 minutes after leaving King’s Cross, we roll into Waverley station, and good-natured bedlam ensues. It’s fortunate we have a 13-minute intermission: anything less could result in a late departure today.

I’d been warned to expect an almost complete changeover of passengers here and that proves to be the case – hundreds of passengers alight for a weekend in the big city, and hundreds more join to escape it!

While all this is happening, platform staff somehow find the space and time to unload empty catering trolleys and replace them with fresh Scottish supplies. North of Edinburgh, LNER offers a different menu, with Scottish-sourced produce forming the backbone of the First Class complimentary offer.

Tourist traffic dominates north of Edinburgh: international tourism is increasing rapidly in Scotland, with exceptional growth over the last five years. An emphasis on high-quality products such as salmon and whisky, the lure of stunning scenery and world-class golf courses, cheaper flights from the USA and China, and the recent weakness of the pound against the US dollar and Euro, has made Scotland a very attractive destination.

The country is also benefiting from the rise of ‘social media tourism’, visitors choosing destinations that look good on platforms such as Instagram – and Scotland abounds in ‘Instagrammable’ views.

Major television series and films such as Game of Thrones, Harry Potter and Outlander, closely identified with Scotland, are enticing many more people to discover the locations where they were filmed. However, all these factors are combining to make some destinations a victim of their own success – ‘overtourism’ is becoming a serious issue as the most popular locations become overwhelmed with visitors and transport infrastructure and hotels struggle to cope.

LNER First Class accommodation is busier as a result but is also benefiting from increased business travel and the introduction of apps such as Seatfrog, which allows passengers to bid for upgrades on Standard Class tickets.

As the only daytime inter-city train over the Highland Main Line (HML) each day, the ‘Highland Chieftain’ carries much of this load, providing a direct link from airports in London, the north of England and Edinburgh to the Highlands. Increasingly, visitors are also favouring the train as a more civilised and eco-friendly mode of travel.

Changeover

According to LNER, an Anglo-Scottish train journey has a carbon footprint five times smaller than an equivalent flight. This favourable ratio should improve still further from December when ‘Azuma’ bi-mode sets eliminate the need to run on diesel under the wires for almost 450 miles between London and Dunblane.

Crew training in preparation for the changeover from HST to ‘Azuma’ has been completed and rehearsal services are expected to be running as this edition goes to print.

“Passengers and staff are incredibly attached to our HSTs. They will really be missed when they go,” says Graeme McKinnie, LNER’s Head of Region for Scotland.

“Crews are having to adapt to a whole new way of working,” he adds. “It’s a completely different layout with the kitchen at one end of the train, rather than between First and Standard Class.”

Some meals on the new trains will be pre-packaged, but the famous LNER breakfasts will continue to be freshly cooked, no doubt to the relief of many regular consumers.

After finally breaking free of the Waverley scrum, we thread through Princes Street Gardens to a brief pause at Haymarket and then make a rapid dash through Linlithgow to diverge from the main Edinburgh to Glasgow route near Falkirk High. Smart operation is vital to avoid interfering with the frequent ScotRail EMU shuttles now speeding between the two cities.

Falkirk Grahamston’s platforms are too short for our 2+9 HST, resulting in a prolonged stop, but we eventually continue north, the urban landscape of the Central Belt gradually giving way to greener, more rolling country.

Stirling is our next call, and a major centre for Scottish tourism thanks to its impressive castle and the wilder, more mountainous country of the Trossachs National Park nearby. It’s a bustling scene as tourists and commuters alight, thronging the platforms as they go.

Having visited the station to photograph its famous semaphore signals several years ago, I’m astonished how much has changed since I was last here. LED signals have been joined by 25kV overhead lines powering brand new Class 385 EMUs, and a new suspension bridge dominates the southern end of the platforms.

As we depart, the electrified Alloa line diverges to the east, not bad for a railway that was freight-only as recently as 2008.

Relaxed

Less than 20 minutes later, we pause at another important destination for Scottish tourism – Gleneagles. Golfers from all over the world come here to test their skills on the famous course. In contrast to our tight schedule further south, the station calls are becoming a little more relaxed as passengers wrestle suitcases – and golf bags – out of the train at each stop.

In fact, the crew tell me this train often recovers lost time north of Edinburgh as longer station stops are part of the schedule, most obviously at Perth. Recovery time is also built-in between Falkirk and Perth.

In May 2019, the head code of the Down train was changed from 1S16 to 1W96 in an effort to improve its timekeeping, identified by LNER and Network Rail as an issue requiring greater focus.

While less of a problem on the core London to Edinburgh leg, on the lengthy single-track sections north of Perth a late-running HST, can cause huge knock-on problems for ScotRail and freight operators. The ‘W’ code alerts signallers to give the train priority treatment and keep delays to a minimum. LNER reports the initiative is having the desired effect, improving reliability and punctuality of the ‘Chieftain’ in recent months.

“It’s our flagship train. We want to get it right,” says Graeme McKinnie.

“Events in London in the morning can affect Scotland at teatime, but by making this a ‘focus’ train we can ensure it gets the priority it deserves.

“Edinburgh is as distant for Highlanders as London is for people living in northern England so it’s essential to have a fast, reliable link.”

By the time we cruise through Strathearn, on the run-in to Perth, a sunny August day is turning into a glorious golden evening. Memories of a hot summer day spent exploring the nooks and crannies of Perth station in the 1980s flood back as we wait time. No sign of any Class 26s or push-pull ‘47s’ on this occasion, but recent vegetation clearance has revealed something I’d never spotted before – the body of a pre-Grouping van body at the south end of the station. Subsequent investigation reveals it is most likely a former Caledonian Railway vehicle once used as a bothy by PW crews, but lost in the undergrowth for many years.

As we ease out under the Glasgow Road bridge and onto the Highland Main Line just after 18.00, there are still 118 miles and two hours to go, and the most spectacular part of the journey lies ahead.

Immediately, the nature of the route changes: double-track gives way to single, semaphore signals are in evidence and speeds are lower, although the HML has had sections of 100mph track since the 1980s.

For many years, only the ‘Chieftain’ could take advantage of them, but more recently Class 170s and now ScotRail’s revamped HSTs make good use of the higher limit.

Half an hour after Perth, we call at another key tourist destination – Pitlochry – recently upgraded and restored to award-winning standards. With its lovely lattice footbridge and attractive buildings, it’s a fine example of traditional railway infrastructure brought up to 21st century standards without losing its character. And there’s the station bookshop!

Regulars

At every stop, all available on-train staff head for the doors to bid farewell to their passengers and help with the unloading of luggage. Regulars depart with a shout of “see you next week” as families and eager dogs wait to greet them on the platform.

After Pitlochry, the landscape closes in as we weave our way through the green tunnel of the Pass of Killiecrankie – occasional glimpses through the foliage giving some clue to the spectacular scenery beyond.

Also visible at many points is the HML’s primary competitor, the A9, which is undergoing a £1billion upgrade to double its long single carriageway sections between Perth and Inverness. What a pity the investment couldn’t have been directed towards the railway instead, thus reducing the region’s reliance on this long and hazardous road.

However, much less costly improvements on the Highland Main Line and elsewhere mean the ‘Chieftain’s’ eight-hour schedule is 50 minutes less than when the train was launched in May 1984. Further improvements to increase speeds and capacity on the HML are in progress and will allow ScotRail to introduce an hourly service of Inter7City HSTs to and from Inverness from December.

Since 2012, a programme of upgrades has increased capacity from nine to 15 inter-city trains per direction each day and, from December, a reduction in journey times of around 10 minutes between Perth and Inverness.

Resignalling work, an extended passing loop at Aviemore and longer, rebuilt platforms at Pitlochry, level crossing upgrades, and line speed improvements are all expected to contribute to an extra 150,000 passenger journeys each year.

Much of the HML was built as a double track but was progressively singled from the 1960s onwards to reduce costs. However, the revival started as far back as 1976 when the 23-mile section from Blair Atholl to Dalwhinnie was redoubled.

For many years, Inverness and the Highland Main Line were also served by ‘The Clansman’, a loco-hauled train which ran via the West Coast Main Line from London Euston. Unusually, it avoided Glasgow and changed from electric to diesel traction at Mossend Yard. Launched by BR in 1974, it was a regular fixture of the WCML schedule throughout the 1980s, although it was gradually relegated in status and finally discontinued by InterCity in the early-1990s.

Today, a connection to Euston and the WCML is maintained by Caledonian Sleeper’s ‘Highlander’ overnight train (more of which later), but passengers wishing to travel during the day must change in Glasgow.

The ‘Highland Chieftain’ enjoys strong support from stakeholders and communities but has been under threat on more than one occasion. In 2010, and again in 2014, through services north of Edinburgh came under review as part of the UK Government’s Intercity Express Programme (IEP) consultation to replace the HSTs. The most controversial proposal was to curtail all ECML trains at Edinburgh and provide connecting trains to destinations further north.

Vigorous campaigning by rail users, business and tourism leaders, politicians and regional media led to the retention of the Aberdeen and Inverness ECML trains using bi-mode trains.

Switch

In late 2019, the fruits of that campaign are about to be realised, with LNER on course to switch Inverness trains from HSTs to nine-car Class 800s from December 9, ending the long reign of the HSTs on Anglo-Scottish trains. Aberdeen trains will start to change a couple of weeks earlier, on November 25, HSTs having plied that route since the late 1970s.

From December, King’s Cross to Edinburgh will enjoy a half-hourly frequency throughout the day – exceptional for a journey of almost 400 miles.

Emerging from the trees we weave back and forth with the A9 as the climb to Druimuachdar begins in earnest. Blair Atholl is passed without stopping, and as the landscape becomes wilder above the tree line, railway and road share the narrowing valley with the River Garry.

At 18.55 we cross the highest point on the British main line railway network, which the famous lineside sign informs us is 1,484ft above sea level. It doesn’t sound much compared to the great mountain railways of the Rockies or the Alps, but be under no illusion about how tough it was to build the railway here or the challenges of operating in the extreme weather conditions that can blow into this sub-Arctic environment.

But there’s no hint of that as we sweep over the top, down the hill and around the curve through Dalwhinnie. Our HST is bathed from the west by the light of a setting sun as we pass the famous distillery and charge on towards Kingussie.

Waiting for us in the loop at our next stop is a train of empty cement tanks, hauled by Colas Class 70, which makes smoky departure almost immediately after our arrival. The HML still sees a couple of daily freights, including the well-known Tesco intermodal train, evidence of which we see as we arrive at Inverness.

Before that though, there’s a long pause at Aviemore, awaiting a late-running ScotRail HST heading for Glasgow, and then another climb to the 1,315ft summit at Slochd. This section of the line was the last to open, in 1898, providing a more direct link to Inverness than the original route via Boat of Garten and Forres.

The on-board catering crew of four are busy clearing away teacups, plates and cutlery in First Class, and making preparations for tomorrow morning’s departure as we cross the majestic viaducts at Tomatin and Culloden in the gathering gloom.

A brief glimpse of the Moray Firth far below is the first hint of our impending arrival in the Highland capital. Before long, we have descended through the trees to cross the line from Aberdeen, and at Milburn Junction, we join it for the final mile or so to our destination.

Slowing to a crawl, we pass the huge stack of Tesco containers and the recently upgraded ScotRail depot. A raised roller shutter gives a tantalising glimpse inside the former Highland Railway Lochgorm Works, but instead of Stag-embellished ‘37/4s’ or ‘47/4s’, an HST power car offers a sign of present and future traction at this famous depot.

With No. 43308 finally at rest under the station roof and the seagulls wheeling noisily above, hundreds of passengers pour out of our train and make for the exit, many into the waiting arms of family and friends.

Our hard-working crew can sense the impending end of their shift as they remove window labels and litter from the train, and make sure it is ready for the journey back tomorrow morning. A local driver arrives to take the HST over to the depot for fuelling and servicing. By 20.20, it eases back out of the platform, heading for a well-deserved overnight break.

On the platform opposite, a DB Cargo Class 67 rumbles away as it waits for departure with the southbound Caledonian Sleeper (CS) ‘Highlander’ for London Euston. Bikes and luggage pile up on the platform as CS staff allocate berths and seats to tonight’s travellers. Tempting as it is to jump aboard for a last trip on an Mk2/Mk3 set before they are replaced, I’m ready to head for my B&B, with the emphasis on the ‘bed’ part.

I say my goodbyes to the LNER crew as they head home, although we’ll all be back here before 08.00 in the morning to do it again on the southbound service.

Thirty-five years on from its launch, the ‘Highland Chieftain’ is about to experience the biggest change in its history. As the HSTs pass into history, at least on Anglo-Scottish duties, a new chapter starts for LNER and the bi-mode era begins on the Highland Main Line.

Fortunately, for regular passengers and occasional travellers alike, the dedicated ‘Chieftain’ crews will provide welcome continuity on this superb journey showcasing some of the best scenery Britain has to offer.