It has taken nine years and 50 million man-hours to build and is the first major new railway in Great Britain for more than a century. ‘High-Speed 1’ opens throughout on November 14 and plugs the UK- at last! – firmly into the European high-speed network.

Formerly known as the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, HS1 brings Eurostar trains into the heart of north London and give the capital city a fabulous ‘new’ terminus in the form of the meticulously-restored St Pancras international.

It also brings to an end the embarrassing trundle through the suburbs of south London that has for so long characterised Eurostar’s ‘classic’ 750V d.c. route to Waterloo.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

HS1 is due to open on time and within budget, a major achievement for such an enormous construction scheme and a triumph for the oftenderided ‘public-private partnership’ method of funding for such projects.

The line’s arrival on the British railway map marks a major shift in the way we think of travel, for, in future, distance measured by length will no longer be so important; from now on, it will be time that matters – as evidenced by the fact that Brussels, not Cardiff, is now the ‘nearest’ capital city to London.

The final services into and out of Waterloo will run on the evening of Tuesday, November 13 and, in a logistical exercise of unprecedented proportions, Eurostar will switch its London terminal overnight to begin services from St Pancras the following morning. This will not only mean an enormous staff upheaval but the transfer of trains from west London’s North Pole depot to Temple Mills, in the ‘east end’.

Tickets for the first HS1 trains (which have been kept at the normal prices despite the faster journeys) have already sold out.

The story of HS1 is really a tale of two separate railways – CTRL Sections 1 and 2. The first, running for 46 miles (74km) from Folkestone to Fawkham Junction where it linked with conventional tracks to Waterloo, was started in October 1998 and opened by the Prime Minister in September 2003.

The second, a 24 mile (39km) route from South fleet Junction to St Pancras, was started in July 2001 with a ground-breaking ceremony at Stratford and was due to have been ceremonially completed with a Royal event on November 6 followed by a public opening eight days later.

Readers requiring full details of the CTRL as a whole are referred to the major illustrated features published in the January, February and March 2002 issues of The Railway Magazine and to a similar major explanatory feature on Section 2 (as far as it had developed by that time) in our June and July 2005 issues. The article you are now reading brings the latter report up to date, although an element of recapping is naturally inevitable.

Although there had been many discussions and false starts beforehand, HS1 effectively originated in February 1996 when the Conservative Government of the day appointed London & Continental Railways (LCR) to design, build, finance and operate the CTRL.

The company then ran into difficulties raising funds but the project was rescued two years later when the new Labour Government put together a complicated rescue package that allowed the first sod to be cut by Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott at the site of Medway viaduct on October 15, 1998.

LCR created two subsidiary companies – Union Railways (South) and Union Railways (North) – to deliver the sections and let the construction contracts.

Once built, Section 1 was owned by Railtrack, but the aftermath of the Hatfield disaster in 2000 left the national infrastructure company in no position to go ahead with the funding of the northern section too, so the Government issued £1.1bn in bonds, paid a £2.2bn public grant and persuaded the US construction giant Bechtel to shoulder a proportion of financial risk by underwriting any cost over-run to £600m.

Project management company Rail Link Engineering, which had successfully designed, managed and built Section 1, was awarded a similar contract for Section 2 and Railtrack undertook to eventually operate both sections as a ‘seamless railway’.

Notwithstanding Railtrack’s collapse shortly after that agreement, the arrangement proved more successful than anyone could have imagined in those dark post-Hatfield days and the project has since progressed smoothly and come in at a total project cost of £5.8bn – well within the overall 1998 budget forecast of £6.15bn.

The remarkable aspect of Section 2 is that more than half its length is in tunnel. Starting at South fleet Junction, the line runs almost immediately through Pepper Hill tunnel beneath the A2 near Gravesend. This tunnel was constructed by building the walls and roof first then excavating 45,000 cubic metres of earth from below.

After passing through Ebbsfleet station, HS1 dives into the 2.5km Thames tunnel and emerges onto a viaduct squeezed between the Dartford tunnel exit road and the QE2 bridge carrying the other carriageway of the London orbital road – an operation described as the engineering equivalent of “threading the eye of a needle”.

This 1.3km-long viaduct is the result of an engineering marvel, for it was propelled one concrete segment at a time over Thurrock marshes by hydraulic rams.

After crossing the marshes to Rainham atop what is effectively a ‘ground-level viaduct’ piled into the soft earth, the line continues past the Ford car factory at Dagenham before diving underground for virtually all its remaining 12.4 miles (20km) – coming up for air only for the brief traversal of Stratford station before crossing over the ex-Great Northern main line and entering the former Midland Railway’s spectacular Barlow trainshed, still as awe-inspiring as the day it was first opened in the Victorian age.

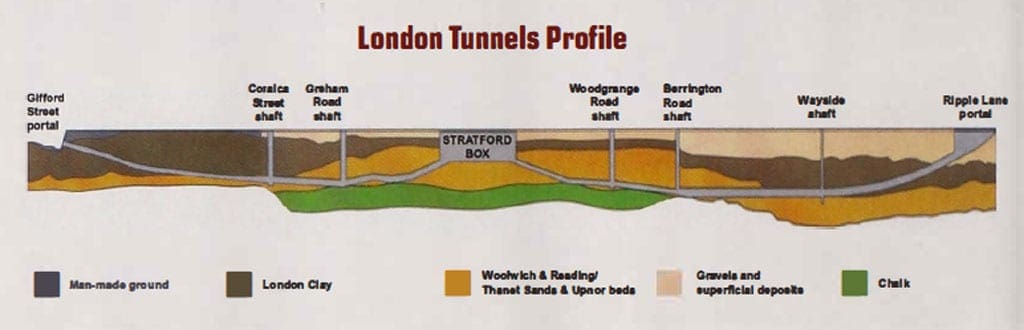

The London tunnel (which is actually formed of two tunnels – east and west – separated by Stratford station) is formed of two parallel bores each carrying a single track, through which trains run at a maximum 143mph (230km/h). Boring began in August 2002 and was completed two years later, using six giant tunnelboring machines (TBMs) manned by teams working around the clock.

Two TBMs, Annie and Bertha, bored 7.5km of twin tunnels from Stratford to the King’s Cross railway lands at Gifford Street, in Belle Isle, passing successfully beneath High bury & Islington Tube station.

Also travelling from Stratford, but in the opposite direction, were Brunel and Hudson, which drove 4.7km under the Central Line and Great Eastern Main Line before breaking through into a ventilation shaft at Barrington Road, in Manor Park. Those TBMs came within 4.3 metres of the Central Line without the need to halt services.

The most easterly stretch was driven by TBMs Maysam and Judy, which bored 5.3km westwards from Dagenham to Barrington Road beneath the LTS Line and District Line. One of the Barrington Road shafts has been left to provide permanent ventilation for HS1.

Altogether, the six TBMs passed beneath a dozen existing railway stations and 600 gas, water and sewerage pipelines. At Maryland, operators had to contend with subsidence of gardens caused by the unrecorded presence of disused Victorian deep wells, but they recovered from the delay to complete their project ahead of schedule.

At Belle Isle, a 2,065-tonne, 75m span tubular bridge was slid into position over the ECML at a rate of ten metres an hour by hydraulic rams over Christmas 2003. The gap between this bridge and the London tunnel portal at Gifford Street has since been covered, effectively lengthening the tunnel by 120 metres.

On April 20, 2006, LCR was able to announce that the main construction works along what was still then ‘CTRL Section 2’ were physically complete and by March 6 this year, the route was sufficiently complete for the first Eurostar set (No. 3313/ 14) to enter St Pancras on a gauging run.

Shortly after that milestone, the track and overhead power systems were handed over to Union Railways North, which in turn was able to pass the whole of Section 2 to Network Rail (as Railtrack’s successor) on July 17.

On that day, the entire 68 miles (109km) of HS1 from the Channel Tunnel to the bufferstops at St Pancras became fully operational and Eurostar duly began driver-training operations three days later.

This intensive testing programme involved two Class 373 sets in use up to 12 times a day between St Pancras and Ashford International as more than 350 personnel from the UK, France and Belgium ‘learnt the road’. Meanwhile, station, signalling and border control staff also underwent training.

As reported in last month’s RM, the first passenger-carrying trains ran from Paris (on September 4) and from Brussels (on September 20), conveying invited guests – and both trains set new records for the city-tocity journey times of 2hrs 3min and 1hr 43 mins respectively.

The next piece of the jigsaw fell into place on October 4 when Temple Mills depot – the replacement for the now inconveniently-situated North Pole facility in west London – was officially opened.

Once the Class 373s have been transferred across after November 14, they are due to have their third-rail current-collector shoes permanently removed, marking the end of a fascinating period in British railway history.

Gallic humour

Finally, in 2009, Southeastern’s domestic high-speed services will be launched on HS1 using Hitachi-built 140mph (230km/h) EMUs. These Class 395 ‘Bullet Trains’ will dramatically shorten journey times to the Thames Gateway and eastern Kent.

HS1 is more than just a railway, for it has leveraged more than £10bn of investment in regeneration schemes around the new stations of Ebbsfleet, Stratford and St Pancras. LCR and its subsidiaries, working with key business partners, are helping to design and construct ‘Stratford City’ and ‘King’s Cross Central’.

Summing up, a proud Eurostar chief executive, Richard Brown, said: “High Speed 1 makes Britain part of the European high-speed network, which now stretches across 2,330 miles of France, Belgium, Holland, Germany, Italy, Spain and beyond – but it means more than that, for the ‘carbon footprint’ left by our trains is up to ten times less than the emissions of aircraft on equivalent journeys, making Eurostar the world’s first truly carbon-neutral train service.”

And SNCF chief executive Guillaume Pepy added with a typically Gallic sense of humour: “More important even than that is the fact that we French will no longer have to be reminded of our greatest defeat every time we travel to Waterloo!”

Original article from The Railway Magazine December 2007.