The life of the great communicator and railway historian supreme, George Dow, is recounted by Robert Humm.

George Dow was a man of many parts. Professionally he was a career railwayman for his entire working life, much of it spent in public relations on the LNER and BR London Midland Region.

He was a patron of up-and-coming railway artists Vic Welch, Hamilton Ellis and Arthur Wolstenholme. In private life he was a writer and historian of considerable talent, a collector of railway memorabilia, someone who encouraged and developed new areas of railway study such as railway heraldry and scale modelling, based on solid historical fact.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

He was a perfectionist in everything he did.

Believing that “no one would ever read it” Dow refused to write an autobiography.

That, perhaps, was his one serious misjudgement. Fortunately, his son Andrew wrote a private memoir, which I have drawn on freely, that preserves the most important aspects of George’s many-faceted life.

In this article I shall sketch his early life and railway career and then concentrate on his literary and artistic talents.

Born in Watford, Hertfordshire, on June 30, 1907, George Dow (GD) was the eldest surviving son of Herbert and Loela Dow (née Currell). There was an older son, Reginald, who had died in infancy and two younger sisters, Phyllis and Betty.

Herbert was an estate accountant, whose grandfather had moved south from Scotland in the 1850s.

George’s early life, in that brief golden era of railways before the cataclysm of 1914, has parallels with several other subjects of this series: childhood walks with mother beside a railway fence, an early favourite company (in this case the Midland, its irresistible crimson livery first seen on a coal merchant’s calendar), Bing and Bassett-Lowke model engines.

The die was cast at a very early age. George wanted to be a railwayman and he was determined to design locomotives.

In 1920 the Dow family moved to Brighton, where George attended Brighton College as a day boy. It was arranged that, upon matriculation in 1924, he would go to Crewe Works as a premium pupil to study locomotive engineering under the chief mechanical engineer Hewitt Beames.

Evening classes

Alas for hopes and plans. Herbert Dow died unexpectedly in 1922 at the early age of 48, and there was no prospect the family could afford the hundred guinea premium (the equivalent of perhaps £5,000 today) required by Capt Beames at Crewe.

George needed work quickly to support his mother and sisters and found it with a London firm of wool importers, the Australian Pastoral Co. Nothing daunted him; he also started evening classes in locomotive engineering in anticipation of his fortunes one day taking a turn for the better.

At the same time there was an urgent desire to exchange the world of Antipodean wool for that of railways.

Through a family connection Dow managed to obtain an interview with Robert Bell, assistant general manager of the LNER, instigator of the pioneering traffic apprenticeship scheme, and for many years responsible for finding promising young men for the company.

Dow was rebuffed in 1926, but at a second attempt in 1927 was appointed a probationary Class V junior clerk in the general section at King’s Cross. The pay was £100 a year, £20 less than his existing salary. That did not matter – he had got his foot on the bottom rung of the ladder. He said that even if there had been a Grade VI he would have taken it.

The real benefits were intangible. His office was next to those of the chief general manager, Sir Ralph Wedgwood, and of CME Nigel Gresley and his team.

Sensing that his future lay on the commercial and not the mechanical side Dow abandoned his locomotive engineering B.Sc studies and turned to the London School of Economics for a course in railway operating , economics and geography. In the time-honoured manner the LNER sent him to out-stations to gain experience of passenger and goods depot work, accounts, signalling and the rule book.

Some of his time was spent in the press section and this marked the beginning of his involvement in railway public relations.

Dow’s first contribution to the way the LNER presented itself to the world came in 1929 when, on his own initiative, he produced two diagrammatic route maps for display in the compartments of suburban carriages on the Great Eastern and Great Northern sections. They were adopted immediately and printed from his originals.

Christened “Dowagrams” they preceded by several years the Harry Beck diagrammatic maps for the London Underground. Together there were 13 of these diagrams, including three for the LMS as paid commissions.

Maps of great clarity were something of a Dow speciality and they appeared in many of his own books and some by other authors.

By 1932 Dow had been appointed a junior canvasser in the commercial advertising department at a salary of £190 per annum, selling advertising space on trains, at stations and on billboards. He worked for, and came under the influence of, the remarkable Cecil Dandridge, who commissioned the superb series of 1930s LNER pictorial posters.

Dandridge also adopted the Gill Sans typeface used extensively for signage and printed material on the LNER and subsequently by British Railways, until replaced by what many regard as the inferior Helvetica ‘modern image’ typeface in the mid-1960s.

In June 1939, at the age of 32, Dow became the LNER’s information officer, in effect becoming the company’s official spokesman in all its dealings with the press, BBC radio, and newsreel companies, promoting its beautiful streamlined trains and the world’s fastest locomotives.

His office also dealt with chambers of commerce, civic societies, railway clubs and individuals seeking information about railway operation. Its enlightened attitude in matters such as lineside photographic permits (handled by his secretary, later his wife, Doris Soundy) helped to lay the foundations of the post-war enthusiast hobby.

Country house

In due course George became a popular speaker and an occasional broadcaster. Particularly during the war he was in great demand as a visiting speaker to small clubs and societies, where he could sometimes provide small morsels of official information out of reach of the censor.

Hardly had he settled into his new post at King’s Cross when he, along with the rest of the chief general manager’s staff, was evacuated on the outbreak of war to rural Hertfordshire.

The temporary headquarters was a country house near Hitchin, called The Hoo, where, as light relief he produced for five or six months a spirit-lifting magazine called Ballyhoo Review. It would be interesting to know whether any copies still survive.

George and Doris Soundy were married in March 1940. Their first child Margaret was born in 1941, followed by their son Andrew in 1943. In 1944 his job description was changed to the more impressive press relations officer.

The humorous magazine Punch took the new title at face value and published a cartoon showing George pressing more commuters into an already overcrowded compartment.

One of his responsibilities was the placing of authoritative articles favourable to the LNER in the national newspapers. One such item was in the London Star evening paper of June 14, 1941, advocating the construction of a full-size tunnel from Paddington to Liverpool Street, a scheme that has taken 75 years to bring to fruition in the form of Crossrail.

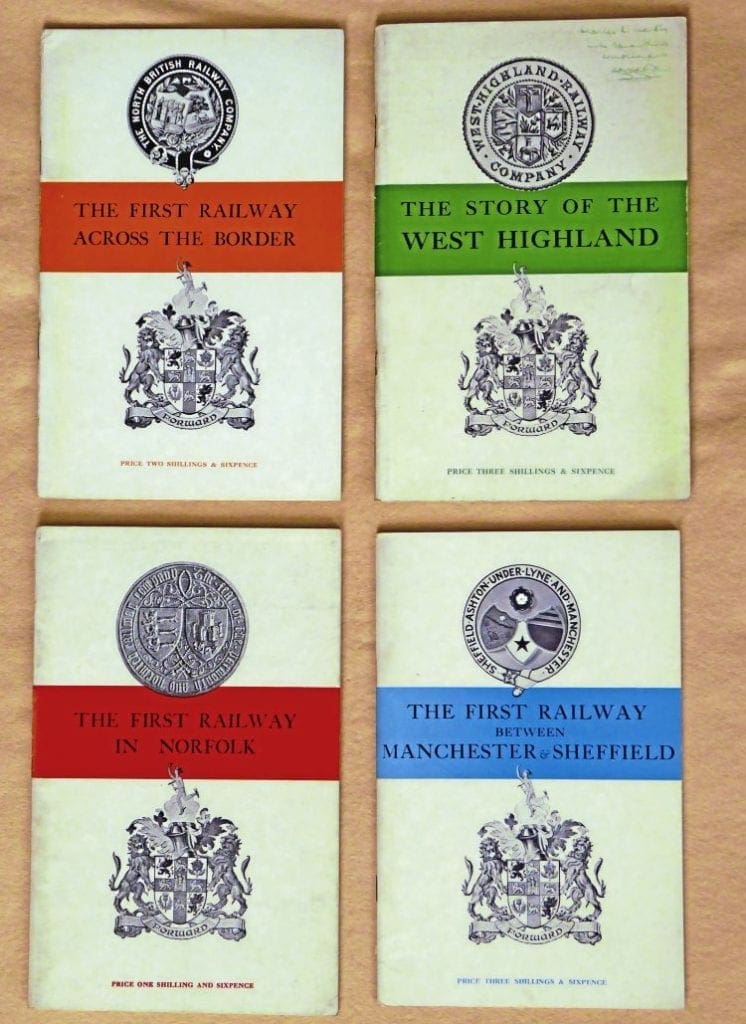

The earliest ‘for sale’ publications written by Dow was a series of four little route histories published by the LNER. In 1944 came The First Railway In Norfolk and The Story Of The West Highland, followed by The First Railway Between Manchester And Sheffield in 1945 and The First Railway Across The Border in 1946.

Seventy years ago the history of an individual line was something quite unusual: today route and branch histories are the chief staple of railway publishing.

Although brief by present standards (the longest is a mere 44 pages) they bear all the hallmarks of the ‘Dow Method’–careful research, folding plans, clear photos and good quality paper.

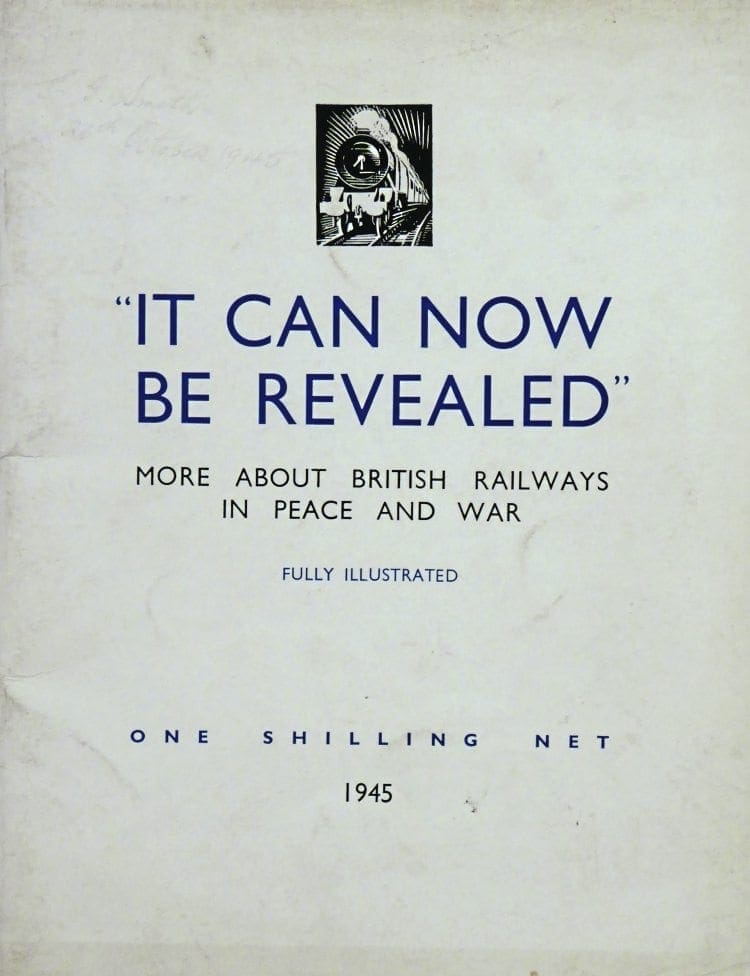

In the same period he wrote anonymously a book for the British Railways Press Office

(a unit sponsored by all the main line companies) entitled It Can Now Be Revealed, one of a series explaining to the public the achievements of the railways in wartime, once more on art paper with superb illustrations.

Immediately upon nationalisation of the railways in 1948 Dow was appointed public relations & publicity officer for the Eastern and North Eastern Regions at a salary of £750 a year. That posting lasted for only 15 months, for in April 1949 he moved to a similar post on the LMR at nearly double the salary.

Considerable power

The move to Euston gave him considerable power of patronage in the field of railway commercial art. In 1950 he commissioned the rising artist Cuthbert Hamilton Ellis to paint a series of 24 colourful historical railway scenes to replace the dull sepia photos in LMR carriage compartment panels.

The subjects, all of pre-Grouping views of LMS constituents, were dictated by Dow. It is no coincidence that the only non-railway scene in the series is of an early LNWR motor bus in Watford High Street, close to GD’s birthplace. Many of the original paintings were displayed in Dow’s various offices and are today at the National Railway Museum.

Another discovery was Vic Welch, at that time a projectionist on the staff of the Public Relations Office. Welch was above all else a practitioner of the photo-realist school of railway art and the antithesis of the Terence Cuneo semi-impressionist style.

As such he was the true successor to the prolific Tom Rudd (‘F.Moore’) of the Locomotive Publishing Company. Welch painted several posters for the LMR, but found greater fame after becoming staff artist for Ian Allan.

He was also responsible for drawing a further 17 ‘Dowagrams’, some in several versions, under GD’s direction. They were for use as carriage panels and station poster display.

A third artist to enter the Dow orbit was Arthur Wolstenholme (ANW), whose distinctive black-and-white scraperboard drawings are familiar to the millions of buyers of Ian Allan publications throughout the 1950s. ANW carried out a number of commissions for Dow, including some superb trains at speed for use as timetable poster headers, and the charming 1953 Christmas card.

Two or three commercially published books appeared from GD’s pen at this time, notably his first full-length work British Steam Horses (1950), which used information gleaned from his engineering studies.

Further publicity booklets to highlight civil engineering achievements were By Electric Train From Liverpool St To Shenfield (1949) and The Third Woodhead Tunnel (1954). But if on balance the Fifties seemed to be a somewhat fallow writing period that was because he was busy researching what was to become his magnum opus, the three-volume history of the Great Central Railway.

Andrew Dow recalled that his father would visit the British Transport Commision Historical Records, “a dusty cathedral of ancient ledgers”, at Porchester Road, near Paddington station every Tuesday evening to comb the MSLR and GCR minute books, financial records, parliamentary papers and other documents.

It was vital in his view to read the primary source material rather than rely upon secondary information and hearsay. He was probably only the second railway historian (W W Tomlinson, chronicler of the NER, was the first) to take this approach.

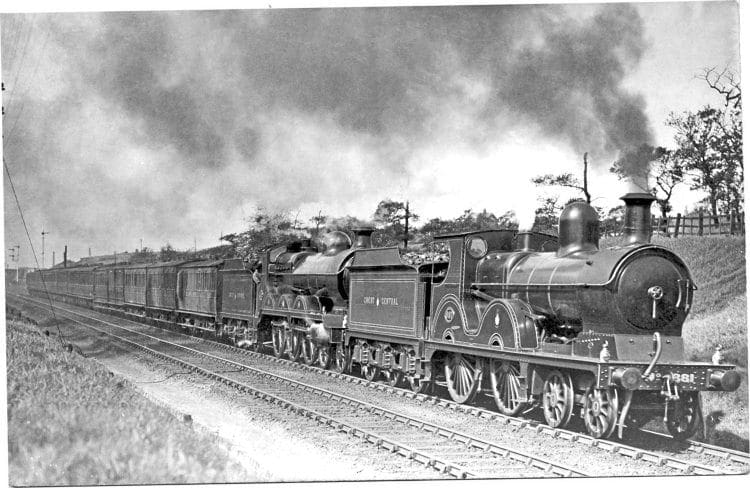

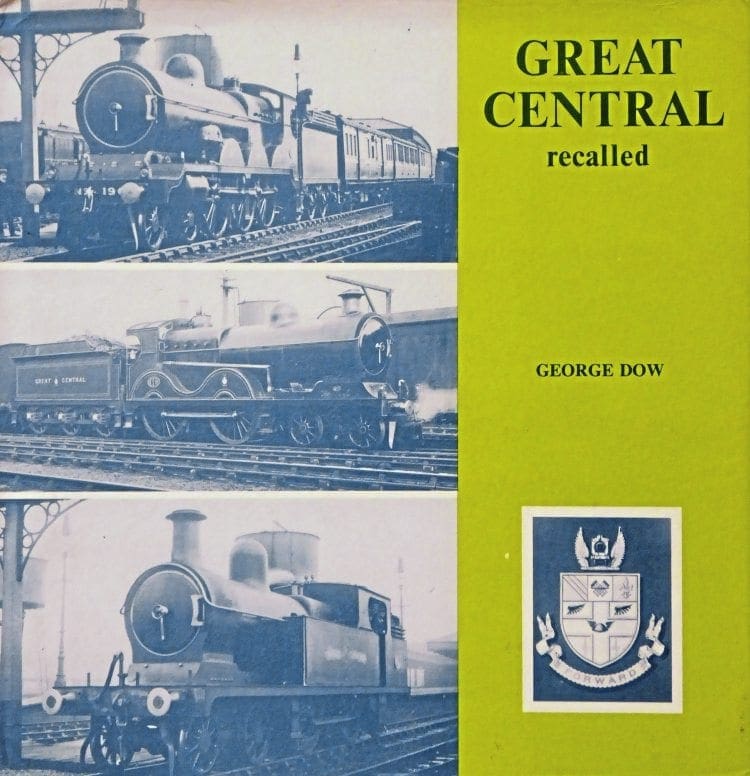

Work on the Great Central history had started as early as 1943 when he published a letter in the LNER house magazine seeking assistance from former GC staff. In all the book occupied his spare time for 22 years.

Why the Great Central rather than his beloved Midland? Largely, I think because nothing worthwhile had yet been written about the GCR and some of its senior officers were still alive, including the charismatic Sir Sam Fay, a man of great charm and persuasion.

On the other hand the first 40 years of the MR had been covered competently by F S Williams and GD was possibly aware that E G Barnes was working on the same subject.

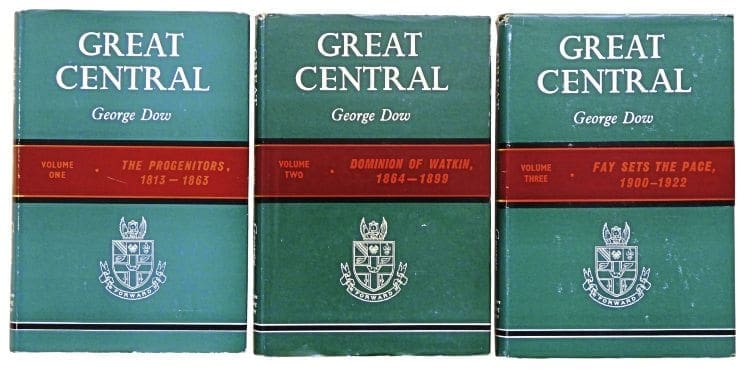

The first Great Central volume – The Progenitors 1813-1863 – was published in 1959 under the Locomotive Publishing Co imprint, by then an Ian Allan subsidiary.

It was immediately apparent that here was a superior kind of railway company history, and one that was printed on good art paper. It stood head and shoulders above the typical works of the period, heavily weighted as they were towards locomotives and train working, way and works, colourful incidents and anecdotes, and sometimes some railway shipping thrown in for good measure. That was not GD’s style.

Another unusual feature was the large number of illustrations, 109 of them, printed in their appropriate places in the text rather than gathered in blocks as was the fashion of the time.

It wasn’t cheap by the standards of the Fifties, although the 35/- cover price bought the reader nearly 300 pages of reliable information. Buyers were not deterred and the print run sold out in two or three years.

Dow had got the result he wanted, though not without a struggle. In his autobiography Ian Allan commented: “George Dow was the world’s worst author to deal with. He was unsatisfiable, pernickety, difficult, aggressive, but in the end forced you to do a good job with no short cuts.”

The second volume of Great Central – The Dominion Of Watkin 1864-1899 – appeared in 1962, and at 422 pages and more than 200 illustrations was a third longer than the first volume. The final volume – Fay Sets The Pace 1900-1922 – came out in 1965.

Taken together they are the most satisfying of all British railway company histories and are unlikely to be superseded.

Final posting

In July 1957 GD moved from public relations to the commercial side of the LMR. By 1958 he was divisional manager at Birmingham and in 1962 came his final posting, at the age of 55, as divisional manager at the newly created Stoke-on-Trent division.

It was the largest on BR, stretching from the industrial North Midlands to North and Mid-Wales, as far west as Holyhead. It included among many other responsibilities the Vale of Rheidol line, BR’s only narrow gauge railway.

GD’s office was in the former North Staffordshire Railway headquarters at Stoke station, where he occupied the NSR boardroom.

The grandeur of this spacious chamber caused consternation among the LM hierarchy, who objected that it was larger than the general manager’s office at Euston. George brushed all that aside on the grounds that the GM never visited the divisions anyway, and it was always he who went up to Euston.

One of the perks of the post was an official car (a maroon Humber Hawk for which he wangled the registration number PRO 1) and a chauffeur – George had never learnt to drive – and this enabled him to live at Audlem, in rural Cheshire, where he bought a house immediately renamed Wyverns.

It was gradually turned into a ‘railway house’ with pre-Grouping lamps, signal finials and cast iron signs in the garden. Railway heraldry and F Moore paintings, several of which he had been able to buy cheaply when the Locomotive Publishing Co shut down, adorned the walls inside.

Another much-appreciated benefit was the divisional manager’s Saloon M999501, which GD used as frequently as he could to show the flag to local dignitaries and to meet the staff of his far-flung domain.

On one of these tours he managed to bend the ear of the Transport Minister, Barbara Castle, about the wish of the LMR management to close the Vale of Rheidol (VoR); at that time it was still run in a time-honoured and rather costly fashion.

GD had ideas for improvements and ways in which the line could be promoted as a tourist asset, but was unable to put into effect.

Barbara Castle listened carefully and in due course the word came down that the VoR should remain open, much to the fury of the LM’s senior officers.

Dow was scolded for his departure from the official line – rural lines were to be closed not encouraged, dammit – but he shrugged it off having already decided to retire not far ahead.

1965 saw the full force of the BR reshaping programme, with many lines in Staffordshire and Cheshire already closed or about to close. It was his wife Doris who suggested that the redundant signs, nameboards, seats, lamps, signalling equipment and the like, instead of being sold to the scrapman for a pittance, should be gathered in and sold by auction.

GD agreed and the first sale in a goods shed at Stoke thus marked the beginning of the organised exchange of railwayana, today a minor industry in its own right.

Dow retired from the railway in summer 1968. He had accrued full pension rights and saw no further reason to stay on. He found the new world of management-speak, endless retrenchment and a humdrum railway devoid of glamour to be completely alien to his way of thinking. Meanwhile, there were more books to write or edit.

The first was Great Central Album (1969), a pictorial work of 112 pages that complemented the great three-volume history.

On similar lines were North Staffordshire Album (1970), undoubtedly influenced by his years at Stoke, and London Tilbury & Southend Album (1981), a neglected outpost of the MR.

All three were published by Ian Allan in their long-running Album series and notably superior to many others of their kind. At a period of generally dire matt book paper Dow prevailed upon Ian Allan to use proper coated stock and to include colour plates too.

Substantial work

A more substantial work was his definitive Railway Heraldry (1973, David & Charles), a handsome book with no less than 48 colour plates.

Armorial devices and their history had interested him at least since the 1940s and he had a large display collection at a time when they could be bought unmounted from the main suppliers, Tearne & Co of Birmingham, for about a pound apiece.

Railway modelling, mainly ‘gauge O’, was another strand of George’s life from his earliest days. He had been the instigator of the Model Engineering Trade Association, one of whose objectives was the setting of agreed standards for scale, gauge, track dimensions, couplings and such. In 1950 he was one of the founders of the influential Historical Model Railway Society, whose president he remained for the rest of his life.

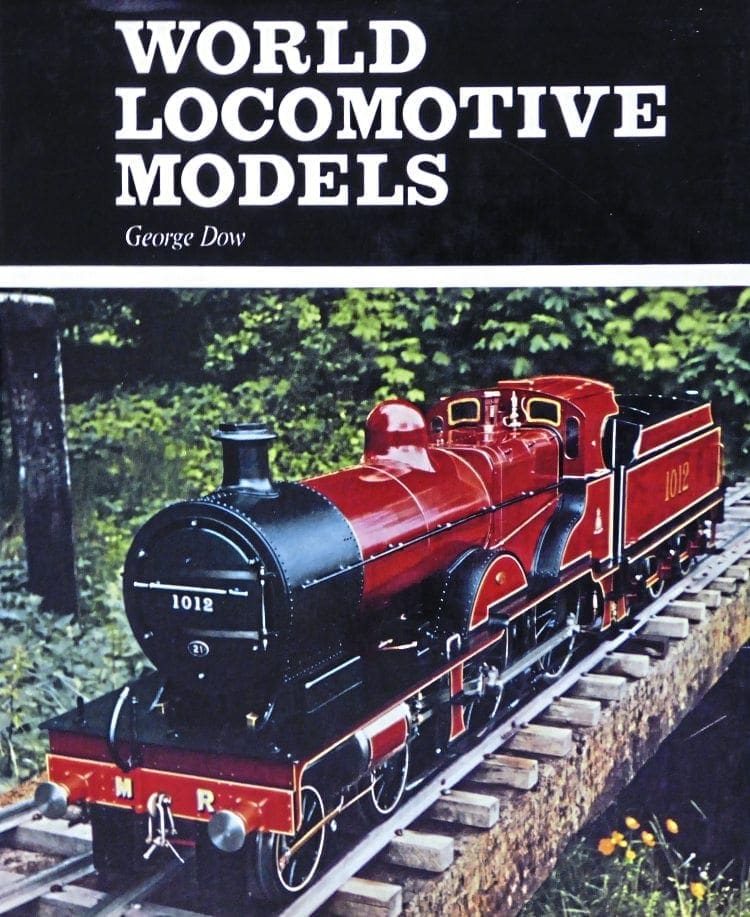

This background enabled him to write World Locomotive Models (1973, Adams & Dart), a compilation of the most outstanding models in the larger scales. Although GD had toyed with the idea of writing in retirement the history of the Midland Railway he came to realise that time was against him.

It would have been an infinitely more complex history than that of the GCR, and the British Transport Historical Records in London were a long way from Audlem. Nevertheless he made two important contributions to MR history.

The first was Midland Style, published in 1975. Subtitled A Livery And Decor Register Of The Midland Railway, Its Absorbed Lines And Joint Lines To The End Of 1922, it was a detailed analysis of station and signalbox architecture, signalling, signs and notices, locomotives, rolling stock, road vehicles, staff uniforms, paint schemes, and the miscellanea that went to create the distinctive ‘Midland look’.

Dow’s second contribution came about in this way. His friend Ralph Lacy had spent many years gathering information upon MR coaching stock with the intention of writing the definitive history.

Following Lacy’s unexpected death his widow Joyce asked GD to edit the book and see it into the press.

Having agreed he discovered that the ‘mass of material’ was hardly more than that, and very little of the narrative had been actually been written.

It was a heavy undertaking for a man in his mid-seventies, but the job was done and published under the title Midland Carriages in two volumes by Wild Swan in 1984 and 1986, GD modestly adopting the role of second joint author. That was George’s swansong and he died at Crewe on January 28, 1987.

With hindsight, GD’s failure to achieve a locomotive engineering career was no bad thing. Within two years the Grouping had reduced the number of chief mechanical engineers by 95% and he might have spent his life as a drawing office dogsbody.

Even if he had progressed – and he was nothing if not determined – by the time he would have been in reach of the top post, say 1957 at the age of 50, there was only one chief mechanical engineer in Great Britain. And he wasn’t designing steam locomotives, or anything else. Nevertheless, it is a pleasant daydream to conjure the vision of a majestic ‘Dow Pacific’ storming Shap.

Instead he found a degree of public recognition and financial security in a succession of railway posts that he enjoyed immensely, with still sufficient energy to write a series of books that will stand the test of time.

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 123 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.