A new type of vehicle for use on both road and rail was trialled in the early 1930s, but never caught on. Alan Dale considers whether early road-rail vehicles were too advanced for their time.

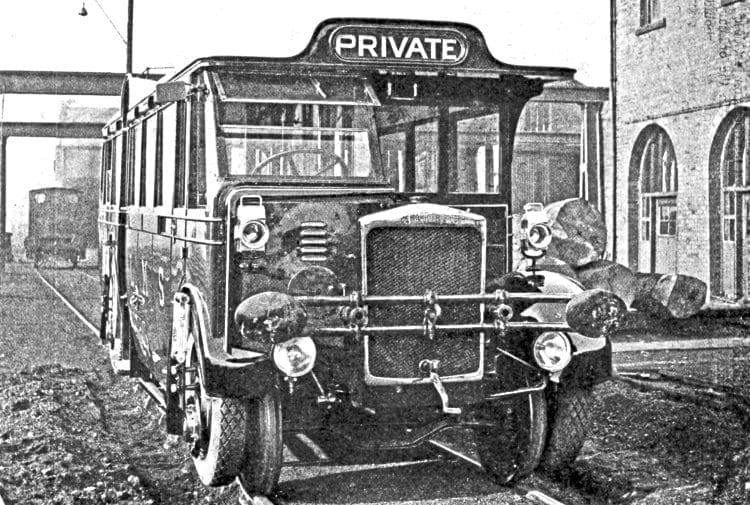

The Ro-railer, or road-rail vehicle, is an innovation that has flickered in and out of fashion and topicality, with changing social and economic conditions.

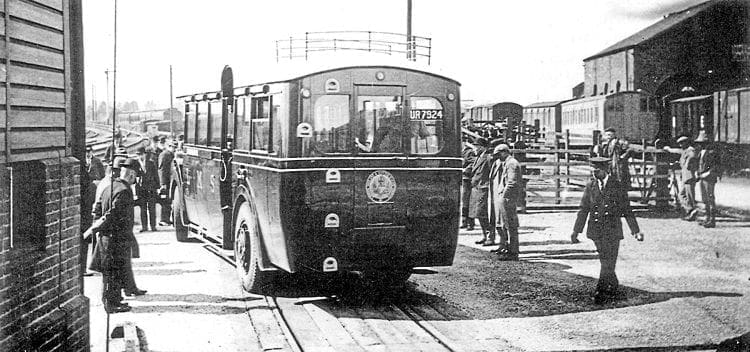

The first Karrier Motors single-deck ro-rail bus of 1931 was a short-lived experiment that was never developed beyond the prototype.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

The same applied to the ro-rail lorry trialled briefly by the LNER. The covered road tractor or locomotive-hauled ro-rail vans of the 1960s had a similarly brief life.

The ro-rail bus was introduced by the LMS after the company had bought the Grade II*-listed 19th century neo-Jacobean mansion Welcombe House, in Stratford-upon-Avon.

This acquisition followed the death of Sir George Otto Trevelyan in 1928. Sir George, father of the eminent historian George Macaulay Trevelyan, had married Caroline Needham Phillips, of whose estate the house had formed part. The LMS considerably enlarged and extended the house, opening it as The Welcombe Hotel in 1931.

Road and rail

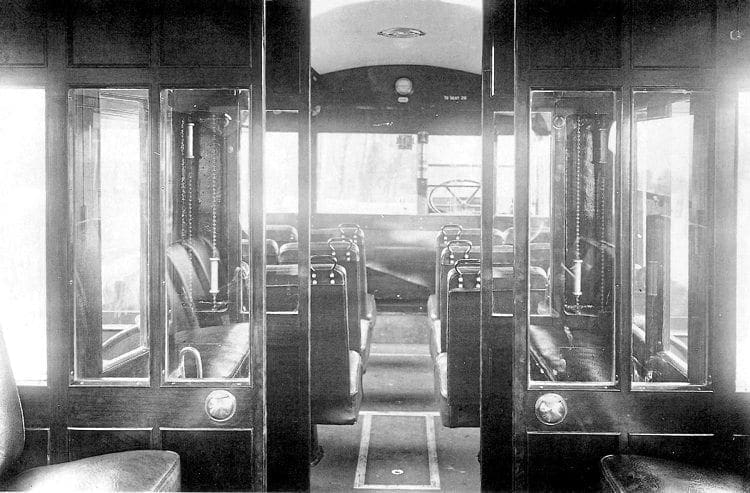

The bus was a single decker, designed by J Shearman, a road motor engineer of the LMS, and built by Karrier Motors of Huddersfield, with bodywork by Cravens of Sheffield. It was equipped with manually interchangeable rail and road wheels.

Introduced early in 1932, it operated on the Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway line (SMJ), between Blisworth and the Stratford-on-Avon goods yard. The road wheels were lowered here, with the rail wheels raised clear of the road surface, by means of the interchanging mechanism and elongated spanners.

The bus then proceeded by road to the Welcombe Hotel on the northern outskirts of the town. The service only ran for a few months.

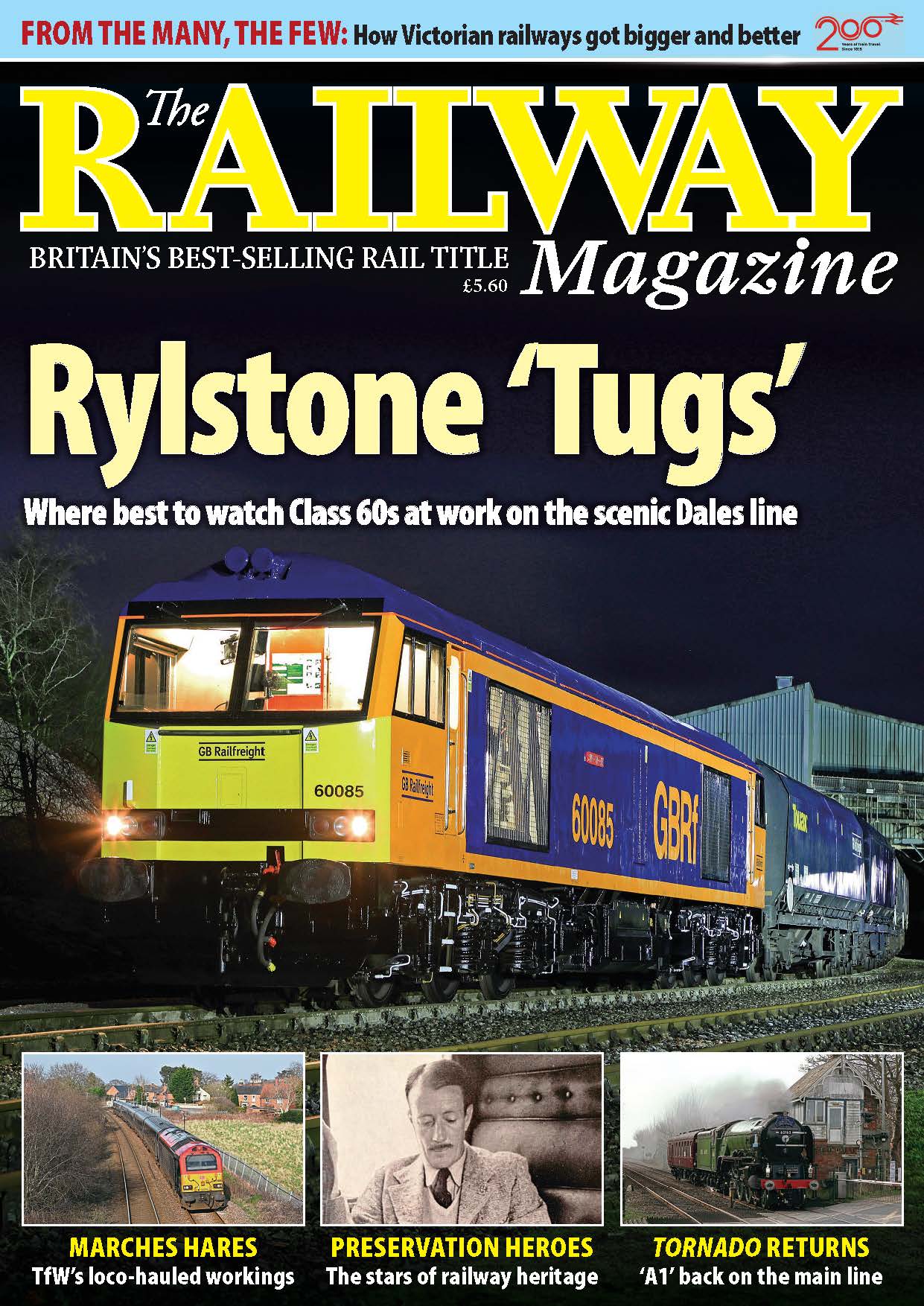

Cravens built the body, providing a forward vestibule with 14 front-facing seats and a rear smoking saloon that contained 12 longitudinal ones. Some of the latter could be folded to augment the roof luggage space.

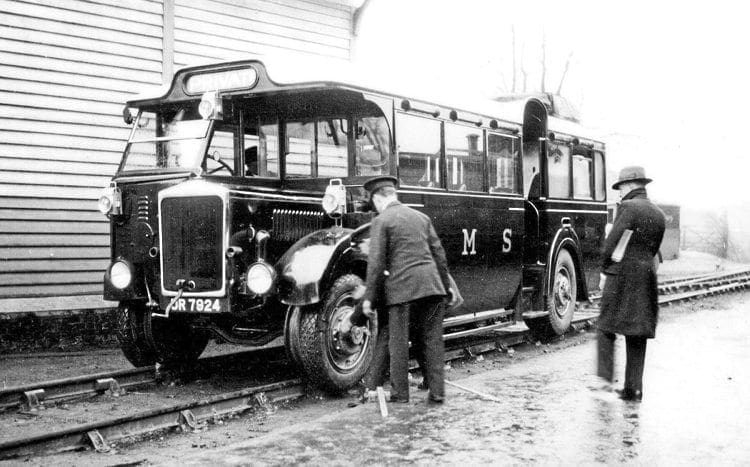

Karrier Motors also built a flat-bed lorry ro-railer for the LNER. This had fixed sides and a removable, hinged tailboard, giving inside body dimensions of 11ft 2in by 6ft 7in.

A sanding device improved rail adhesion, thereby preventing wheel-lock and skating, while allowing optimum use of the servo-assisted brakes. The wheel interchange mechanism, on all four wheels, was the Karrier ‘C’ slot-type.

This incorporated notable advances on the eccentric-based design utilised in the original system. An inner hub carried each pneumatic-tyred road wheel, plus a cranked sleeve that had the road wheel’s ‘C’ slotted outer hub mounted upon it.

Permanent way staff used this unit to take men and materials to site from their depot. It travelled by road to a point where it was convenient to access the track. Conversion to rail mode allowed access to sections of line with unsuitable or distant roads, such as between Bridge of Orchy to Tulloch, or Fort William to Mallaig.

Karrier’s LMS experimental bus design highlights the extent to which road and rail technology of the time could be effectively combined. Powered by a 37.2hp petrol engine, the transmission gave top gear ratios of 7:1 and 4.2:1 for road and rail, respectively.

Recorded fuel consumptions were 8mpg for road and 16 for rail. The wheel base of 17ft 1in and road wheel track of 6ft 3½ for the bus reflect its 26-seat capacity. It was designed to carry three tons in total (i.e. passengers, luggage and crew). This specification complied with the Ministry of Transport and railway regulations.

These dimensions compare intriguingly with the length and capacity of later railbuses and DMU carriages. The five Park Royal railbuses, for example, were 42ft long and seated 50, but without the ability to use the roads.

Eccentrics

The wheel interchange mechanism comprised axles that extended through the rail wheels to the front and rear outer pair of road wheels. The latter were mounted on eccentrics, hence their centres were eccentric to those of their rail counterparts.

The rail wheels, being smaller than the road ones, could be locked, concentrically to the road wheels, clear of the road. The crew used long-handled spanners for this, whereas today, the design would almost certainly incorporate a hydraulic system, to reduce the required time.

The interchanging from pneumatic-tyred road to flanged rail wheels was accomplished as follows. The bus was driven onto any track section where the road surface was level with the top surfaces of the rails.

The driver manoeuvred the ro-railer until the rail wheel flanges were directly over the respective rails. The road surface sloped gradually downwards from this point, dropping below the rail surface height. Driving the bus slowly forward allowed the rail wheels to come into contact with the rails, relieving the vehicle’s road wheels of its weight.

The driver then rotated the road wheels on their eccentrics, raising them above rail level and locking them to the chassis with a pin.

ROBERT HUMM COLLECTION

This was accomplished by raising each road wheel in turn, using the assembly attached to the vehicle body above each wheel set. Securing the rail wheel by bolts enabled the ro-railer to proceed. This arrangement prevented the road wheels from rotating during rail travel. The wheel interchange sequence was reversed before returning to road usage.

The coachwork is an interesting period mixture, with its ‘half cab’ and central entrances on both sides, the latter feature immediately betraying the hybrid usage. The raised roof above each door provided additional headroom for passengers boarding from platform level.

The side windows, although not an unusual pattern on buses of the period, resembled those of earlier railway saloon coach bodywork. Their full depth droplights were relatively rare in British road or rail coachwork.

The LNER’s Karrier Motors lorry incorporated a significantly better wheel interchange system than that used on the LMS ro-railer bus. All four lorry wheel sets included the new Karrier ‘C’ slot mechanism. This comprised a road wheel on an inner hub, and a ‘C’-slotted outer hub, mounted on a cranked sleeve carrying the road wheel.

The two wheels were concentrically aligned for road use, revolving as one assembly, driven by a pair of pins passing through both hubs.

Competition

Conversion from road to rail operation required lifting of the road wheels, using the pivoted eccentric, which rotated about a crank-mounted fulcrum pin. The rail wheel hub supported the road wheel during this realignment, using a bush surrounded with an oil bath.

Inserting two driving pins through a chassis-mounted bracket and slipper block assembly, into two bosses on the eccentric, secured and immobilised the lifted road wheel.

The outer hub’s driving flange transmitted the drive and locked the fulcrum pin while the road wheel was lifted. An arrangement of holes around the driving flange allowed the insertion of a specially designed tool that engaged the fulcrum pin.

The eccentric contained a cam trigger, opposite the pin, engaging a slot in the driving flange, preventing wheel collapse after withdrawal of the driving pins.

Road-to-rail changeover began with the lorry driving onto a ramp, leading to rails, thereby lifting the road wheels above the ground. Following removal of the two driving pins, the wheel was turned, positioning the cam trigger at the bottom.

The fulcrum point had to be directly above the axle centre, to achieve the maximum 9-inch lift. Insertion of a bespoke lifting tool through a convenient driving flange hole located the tool in the fulcrum pin. Depressing the trigger allowed swinging of the wheel upwards, before securing it, by inserting the two driving pins, through the slipper block, into the eccentric.

The lorry had a four-cylinder, 31-48hp engine, four-speed gearbox and cone clutch. A prop shaft provided rear axle drive, with mechanical universal joints at both ends, to a worm wheel and differential. Fully floating, high-tensile steel axles, unloaded except for torque, transmitted power to the 32-in rail and 38-in by 7-in pneumatic-tyred road wheels.

The maximum legal road speed was 30mph, with 37mph for rail. The 6.5:1 top gear ratio was adequate for a goods vehicle in rail operation, as opposed to 7:1 for the bus. The chassis boasted 12-volt lighting and grease-gun lubrication.

After acquiring the SMJ in 1923, the Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway, and the LMS, had wanted a through Stratford to London connection. Both the Stratford to Marylebone and Stratford to Euston options, offered via the SMJ route, were shorter than the GWR alternative via Leamington.

The 1923 Grouping ended the co-operation whereby through coaches were attached to Great Central trains at Woodford Halse, having been worked over the SMJ. This was because of the LNER absorbing the GCR, while the SMJ became an LMS route.

Competition from road transport also led the LMS to seek a direct link to Euston from Stratford-upon-Avon. This requirement, together with the potential to increase traffic for other little-used lines, led them to order the ro-railer.

Non-stop running

The directors realised Stratford’s theatre, together with their own recent investment in the Welcombe Hotel, had created an increasingly important destination. The bus took passengers by road, from the hotel, to Stratford station, then by rail via the SMJ line to Blisworth, to change for Euston. Non-stop running was envisaged from Blisworth to Stratford. However, single-track working often caused pathing delays at Towcester and Kineton.

Despite its innovative features, the ro-railer was only in revenue-earning service for a few weeks. It was tested on the Hemel Hempsted to Harpenden branch, following delivery in 1931.

On April 23, 1932 – William Shakespeare’s birthday – the LMS launched the service at Stratford-upon-Avon. A local bus company objected to what they saw as encroachment into their operating territory. Ironically, the objectors didn’t offer a route from the Stratford LMS station to the hotel.

The LMS offered a flat, sixpenny (6d) fare, on intermediate fare stages, for passengers boarding the ro-rail bus in the town. This proved unattractive, but diffused the dispute. The main benefit was that passengers had no need to remove their luggage from the bus on arrival at the station. They remained seated, while their vehicle changed from road to rail operation.

The ro-railer lacked rail adhesion, being relatively light, at seven tons two cwt unladen. This made adequate uphill speeds very difficult to maintain on the SMJ gradients, with drivers consequently seeking maximum downhill acceleration.

The suspension system was dynamically hard, with little discernible damping of the savage impacts from rail crossings and joints. The inevitable quickly followed, a front axle component breaking in service, near Byfield. Removed to Wolverton Works for repairs, it probably ended up as a road vehicle for a few years, given the renewal of its road registration.

WARWICKSHIRERAILWAYS.COM

A LMS board meeting abandoned plans for more such units, late in 1932.

One ro-railer legend concerns the alleged deputising for an unavailable loco and coach on a Stratford to Broom Junction service. Apparently, the Broom turntable was unavailable (the East to West triangular connection being still 10 years into the future), necessitating returning in reverse.

The LNER lorry showed the potential of goods ro-railers to avoid double loading and unloading. Large complexes of sidings like the former Slough Estates system removed the requirement to transfer goods from train to road for door-to-door delivery.

That was only at the Slough end of the journey, however, unless the goods happened to have originated from a similar complex elsewhere. Greater speed was possible, for the rail section of a ro-rail journey, offering attractive potential time savings. Reduced tyre wear was another potential bonus.

The advent of containerisation, the motorway system and consequent increases in road haulage and passenger coach speeds all contributed to the abandonment of the ro-rail concept. British Road Services’ ro-rail covered vans of the 1960s had interchangeable road and rail wheels at one end.

The other end was designed to allow attachment to an articulated lorry tractor for road use. Rail operation utilised a four-wheeled rail chassis to couple conventionally to a locomotive at one of its ends, and support the wheel-less end of the ro-rail van at the other.

The ro-rail vans had, additionally, a male coupling at the wheel-less end and a female one at the wheeled end. This enabled a train of vans to be marshalled, with the four-wheeler chassis at the end of the train, coupling to the engine. This system was discontinued once container traffic developed.

Many of the branch lines that vanished after Beeching might well have benefited most from ro-railers, but social, political and economic change had left them behind. ■

Read more Letters, Opinion, News and Features at https://www.therailwayhub.co.uk/ and also in the latest issue of The Railway Magazine – on sale now!

The Railway MagazineArchive

Access to The Railway Magazinedigital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 123 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archivebutton above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.