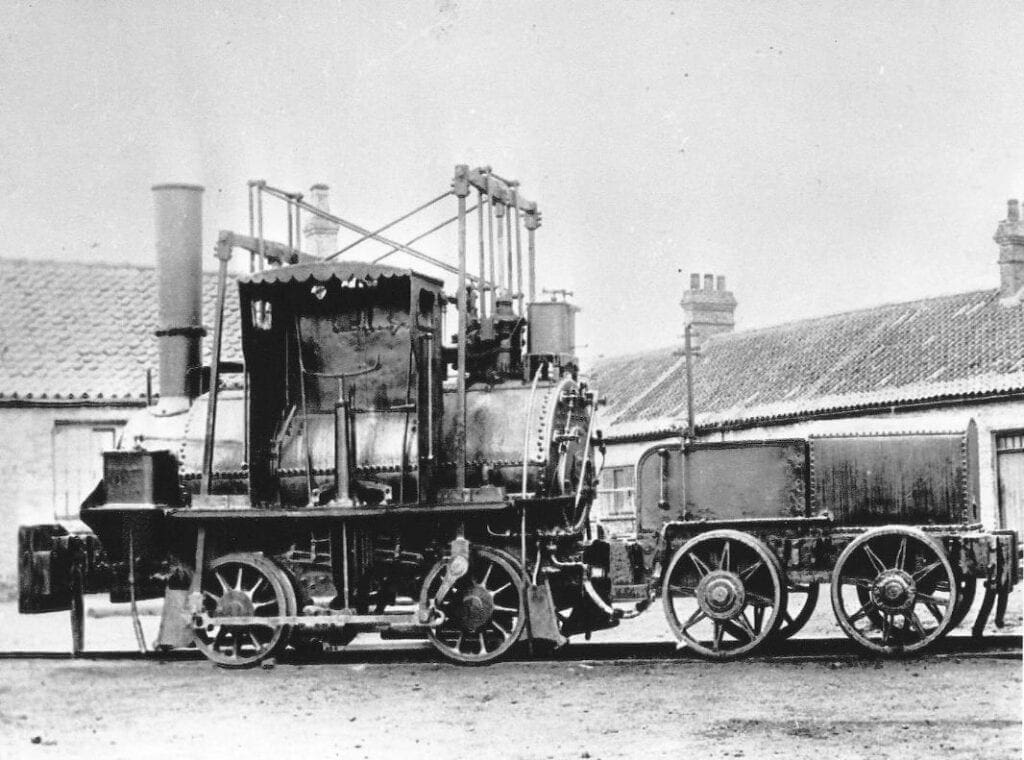

Researchers in County Durham have solved one of the longest standing early railway mysteries that disproves claims linking a Hetton Colliery locomotive to George Stephenson.

Dr Michael Bailey and Peter Davidson have proved that the locomotive was not built by George Stephenson, as previously claimed, and therefore not one of the UK’s oldest surviving engines, said to predate famous locomotives such as Rocket and Locomotion No. 1.

The findings follow a seven-month investigation into the engine, based at Locomotion in County Durham.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Dr Bailey and Mr Davidson conclusively report that the locomotive was built circa 1849 and is named Lyon after John Lyon under whose land, Hetton Colliery won much of its coal. There is no evidence that the locomotive has any parts dating back to the original Stephenson locomotives.

Lyon was one of three sister engines constructed at the colliery between 1849 and 1854, named Fox and Lady Barrington. The three locomotives were driven by three brothers: Jimmy, Jack and Dick Ford. Although the fate of Fox is unknown, Lady Barrington’s boiler exploded in December 1858 – tragically killing Jimmy and his son.

Dr Bailey and Mr Davidson were able to confirm that the engine spent its operational life of more than 60 years hauling coal wagons at Hetton Colliery in County Durham.

World’s oldest working locomotive?

The ‘mystery’ began when exaggerated claims of the engine’s historical pedigree, issued by the colliery in 1902, led to extraordinary national interest.

News reports at the time described Lyon as the ‘world’s oldest working locomotive’.

With its new-found fame, the locomotive was preserved after being withdrawn from service in 1912, and went on to lead the 1925 centenary procession for the Stockton and Darlington Railway.

Whether through accident or more likely, as a deliberate plan to impress the colliery owners, Lyon’s fabricated history lasted for many years and it is only now with more modern records and research techniques, that the myth can be conclusively laid to rest.

The project began in April last year and saw world renowned specialists: Dr Michael Bailey and Peter Davidson, conduct a forensic-like examination of the locomotive and tender alongside detailed archival research.

Dr Michael Bailey said: “I am pleased that as a result of this project we have been able to solve the Hetton mystery and confirm the locomotive’s true identify. Although it would have been exciting to uncover links to early Stephenson engines, the benefit to us today is that this remarkable locomotive would undoubtedly have been scrapped were it not for the tall tales surrounding it.

“The result of the Hetton myth is that we have an early and unique example of an industrial steam locomotive which tells us a great deal about the construction of early engines and components. What is most surprising is that the myth endured for so long and that the durability of the outmoded designs enabled the engine to continue operating for such a long time.”

Lyon was built to an unusually antiquated design for the times with vertical cylinders, set into the boiler crown, and a vertical motion. This may have helped give the myth of the engine’s early history more plausibility as it looked similar to older, Stephenson engines. Although built in 1849, the locomotive represents the ultimate version of the Stephenson-built Killingworth locomotives.

The locomotive today is formed of parts from three main eras, with major modifications carried out in 1882, and replacement buffers fitted in the 1960s. The original wooden tender was completely replaced in 1882 and only the frame and wheels remain from this vehicle with heavy modifications carried out by LNER in 1925.

One of the key breakthroughs came when the team discovered that the technology needed to make long sheets of wrought iron plate used in Lyon’s boiler did not exist before the 1840s, ruling out an earlier construction date.

The team also found evidence of a serious accident and a major repair to the front cylinder which would have ordinarily been sufficient to see the locomotive written off. However, the extensive and uneconomic repair, suggests the ‘celebrity’ status of the engine was sufficient to have saved it form the scrapyard.

Dr Sarah Price, Head of Locomotion, said: “It’s not every day that we have the chance to learn more about the stories of the early locomotives in our collection and I am really grateful for Michael and Peter for leading this project. Visitors have really enjoyed seeing them at work, asking questions and finding out more about the engine and the investigation.

“There are several other engines in the collection we would love them to have a look at and I hope we will be able to work together again soon. The findings of the Hetton project will help inform the way we tell the story of the early railways as we develop the wider Locomotion site in the coming years.”

The report includes recommendations to prepare the locomotive for the upcoming bicentenary of the Hetton Railway in 2022 which include budget for safe removal of asbestos, allowing a programme of renovation and the reassembly of connecting rods. Due to its age and mechanical condition, the engine will not be able to return to steam.

The current project builds on earlier doubts as to the truth of the Hetton myth, explored by Michael Rutherford in 1995 and Jim Rees in 2001.

Dr Michael Bailey and Peter Davidson plan to publish the full results in a paper at the Early Railway Conference to be held in Swansea in 2021.

The last project of this type involving the National Railway Museum took place 20 years ago when Dr Bailey worked on an investigation into the early history of Stephenson’s Rocket.

The results were published in the book ‘The Engineering and History of Rocket’. This project is the first of its kind to take place at Locomotion in Shildon.