September 1984: Bodmin and Wadebridge 150 John R. Smith takes a final trip over one of Cornwall’s pioneer lines and commemorates its 150th anniversary.

ONE hundred and fifty years ago this month, on September 30, 1834, the wooded slopes of the Camel Valley in Cornwall were disturbed by an unfamiliar sound: the echoing whistle of a steam locomotive. The Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway, Cornwall’s first line to be powered by steam, was fully and ceremonially being opened for business.

ONE hundred and fifty years ago this month, on September 30, 1834, the wooded slopes of the Camel Valley in Cornwall were disturbed by an unfamiliar sound: the echoing whistle of a steam locomotive. The Bodmin & Wadebridge Railway, Cornwall’s first line to be powered by steam, was fully and ceremonially being opened for business.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

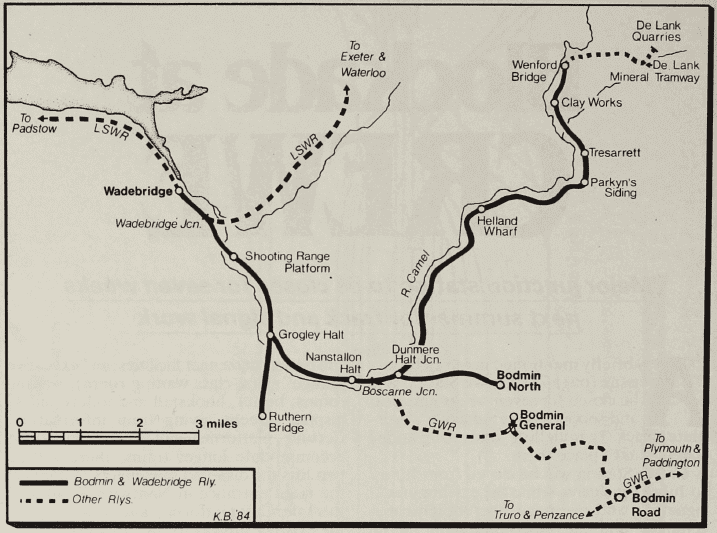

Sanctioned in 1832, the money for this enterprise was raised by local people; shopkeepers, farmers and tradesmen found the £35,000 needed for the thirteen miles of track from Wadebridge to Wenford Bridge on the fringe of Bodmin Moor. There was a half-mile branch to Ruthern Bridge and another into the town of Bodmin itself. The line between Wadebridge and Bodmin had been in use since July 4, 1834.

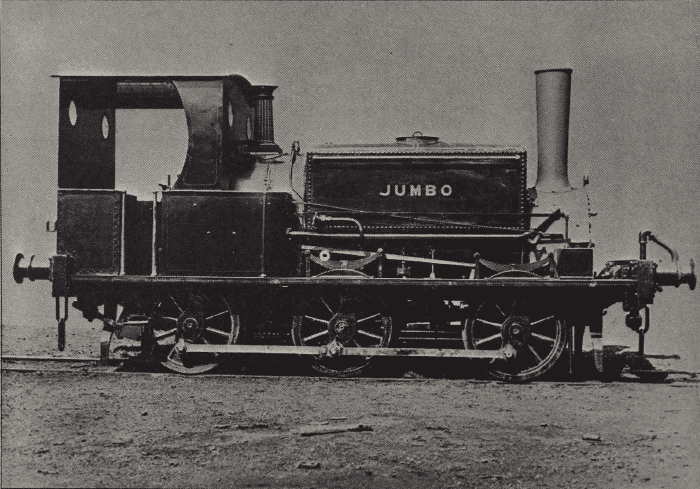

This was essentially a local railway and freight traffic was its prime purpose: sea sand for manure, coal from Wadebridge, and minerals from the mines and quarries of the hinterland. No grand designs for expansion were mooted and the construction of the line relied on local materials and skill for its success. The rails were laid on granite blocks, as was usual in Cornwall, the iron work for the bridges came from the foundry in Wadebridge, and the coaches and goods wagons were built in the company’s own shops by the staff of two blacksmiths and two carpenters. A locomotive was beyond the resources of the town, however, and Camel, a twelve-ton 0-6-0 tender engine, was ordered from the Neath Abbey Ironworks and shipped in to work the line.

There was enough rolling stock on that opening day to carry 400 people over the entire line at a modest maximum pace of 10 m.p.h., and impressive enough that must have seemed; the band of the Royal Cornwall Militia in full uniform added to the sense of occasion.

The line quickly settled down to a useful, if unspectacular, existence. Passenger trains ran between Wadebridge and Bodmin, and occasionally on the Wenford branch for excursions. The company was very progressive in its promotion of cheap tickets, excursions to flower shows and the like, and on one macabre day a special train was run to witness a public execution at Bodmin. As the line conveniently ran beside the walls of Bodmin Gaol, the passengers were able to view this event from the comfort of their seats.

Credit for this able and enterprising approach must go the line’s first Superintendent, Hayes Kyd. The Superintendent was not without his problems in the early days, however: bad weather washed out bridges, snow brought a standstill to operations, and there were mechanical problems too. Mishaps recorded in the day book include “broke off chimney of the engine” (how?) and “stopped the engine in consequence of the wheels being of different sizes”. Perhaps the staff at Wadebridge were still not altogether familiar with steam locomotives.

The greatest hindrance to improving receipts was the line’s isolation from the rest of the railway system, and in 1845 the headquarters building at Wadebridge became the focus of a Machiavellian power struggle between two railway giants which was to compound the problem for the rest of the century. Both the Great Western and the London & South Western Railways were involved in Parliamentary battles over routes from London to Exeter, with the aim of opening-up Devon and Cornwall to their particular companies. In a sneaky move in 1847 the South Western bought the Bodmin & Wadebridge with the objective of establishing a bridgehead in enemy territory, but lack of finance prevented the company from making physical connection with its new property for another fifty years.

During the interim the Bodmin & Wadebridge continued as before: a few new locomotives appeared by sea from “upcountry”, but otherwise the old wagons rolled over the granite blocks with their loads of sand and coal as they had from the inception of the line. The LSWR directors would appear from time to time and a S special train would be run, featuring the company’s only first-class carriage. However, it was not until 1895 that the LSWR finally reached Wadebridge and the line was absorbed into a larger scheme of things. The venerable old coaches were taken up to Bodmin Waterlof’ and put on display for Londoners to gaze in awe at these antiques two are now in the mllseum at York.

The situation at Bodmin was by now, quite complex, as the Great Western had built its own branch from Bodmin Road into the town in 1887, and then joined the Bodmin & Wadebridge by a circuitous route around the outskirts to Boscarne Junction in 1888. The original Bodmin station was rebuilt by the LSWR, and three new halts were opened on the old line at Grogley, Nanstallon and Dunmere. Train services established a pattern which was to persist until closure, with Great Western trains from Bodmin running through to Wadebridge, while the South Western ran Bodmin to Padstow services calling at all the halts, which the GWR was not allowed to do.

At Wenford Bridge the granite quarries of De Lank were connected to the branch by a rail incline in 1890, and additional traffic was provided by new china-clay dries at Penpont. just south of Wenford Bridge. Wadebridge developed into an important railway centre for the LSWR in Cornwall. with a locomotive depot capable of undertaking quite heavy repairs. and more than fifty trains a day used the station in its heyday.

Almost any type of locomotive could be seen here. including in later years the Bulleid Pacifics, but on the Bodmin & Wadebridge itself the passenger traffic was mostly in the hands of Adams “02“ tanks. The locomotives which had the most famous association with the line. and the Wenford branch in particular. were of course the Beattie 2-4-0 well-tanks. There were normally three shedded at Wadebridge, and they had been used on the line since 1893 when the first one had been brought in by sea; they continued to work the branch until 1962—a remarkably long service for locomotives that were already elderly when first introduced.

Although it must have seemed to many that the Bodmin &Wadebridge line was an immutable part of the landscape, the cold winds of the Beeching plan were to blow through the Cornish valleys and leave little unchanged. Dieselisation and other economies of operation failed to do more than gain a few years reprieve, and in January 1967 the last train ran from Wadebridge to Bodmin. A little freight traffic used the yard at Wadebridge until 1978, when the station, which had given employment to 134 men at its peak, closed for good. Much to the joy of all railway enthusiasts, the Wenford branch survived, and continued to provide a thrice-weekly load of clay from the dries at Penpont, routed via the old GWR station at Bodmin General and Bodmin Road to Fowey docks.

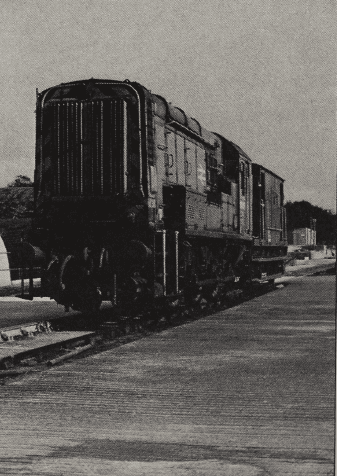

In August of last year I was lucky enough to be invited for a trip up the branch in the brake van of the clay train. We left Bodmin Road on a superb summer’s day behind St Blazey‘s No. 08 945. The “O8” diesels took over the ‘branch workings after “’03”s had been used for a brief period, and were found to be worthy successors to the Beattie The Railway Magazine September 1984 tanks. After the reversal at Bodmin, and another at Boscarne Junction, we were on to the Bodmin & Wadebridge itself, climbing up from Dunmere through the beautiful Camel Valley.

The great glory of the line has always been the scenery it passes through, and from the brake van we were in a splendid position to appreciate it. Trees overhung the track so close on both sides they brushed against the engine, pheasants flew up at our approach and rabbits ran across the track. At Wenford we marshalled our train of china-clay “tip” wagons then made the return journey, the woods echoing to the squeal of flanges on the tight curves.

Enjoyable though it was, that trip was tinged with a mood of sadness for we all knew the line was doomed. Traffic was sparse, and earlier in the year it had been agreed in consultations with English China Clays that the expense of operating this last stretch of the Bodmin & Wadebridge could no longer be justified.

In September 1983, an “08” brought down the last load of clay from the dries, and the line fell silent. A continuous record of 149 years of service to the area is something of which Hayes Kyd would have been proud, as would all those worthy men of Wadebridge who so long ago had faith in a project, “their” railway up the Camel Valley. For railway enthusiasts everywhere, the “Wenford” was a legend in its own time.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on from just £6. Not a subscriber? No problem…. Just click here to see the latest offers. Existing subscribers purchase the archive here or by calling our customer service team on 01507 529529.