Trevor Gregg looks at the history of the Wansbeck Valley Railway in rural Northumberland and recollects his journey, 57 years ago, on the ‘Wansbeck Piper’, the final train to travel over the route.

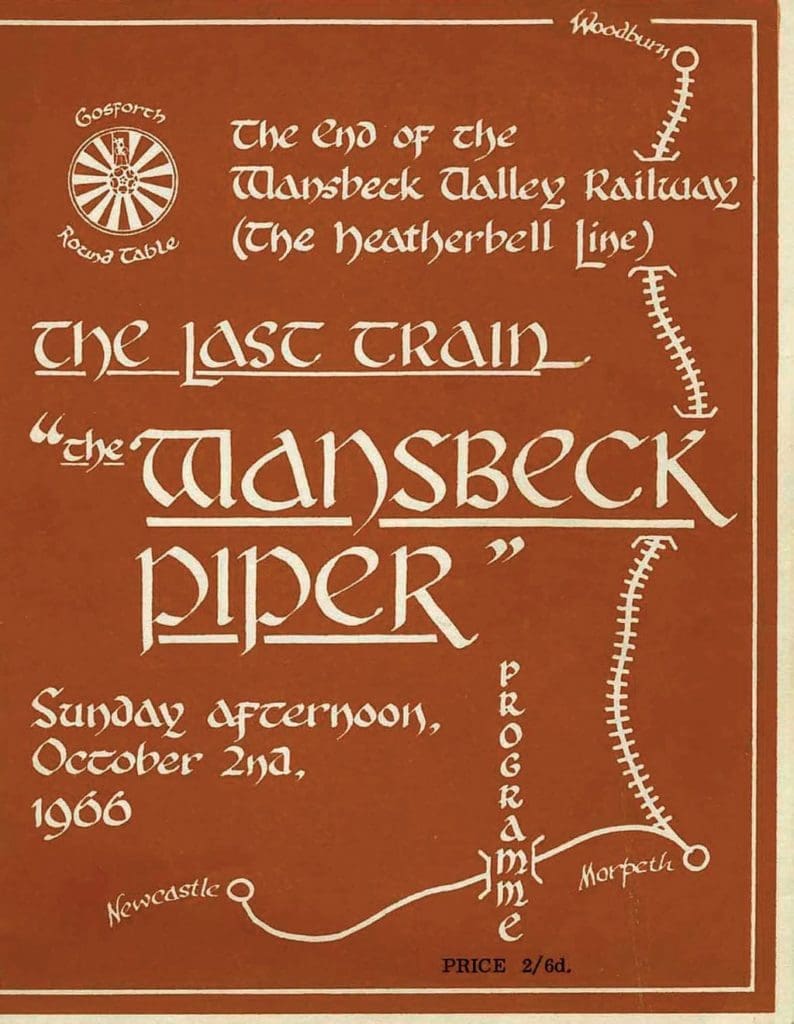

On the afternoon of Sunday, October 2, 1966, an 11-coach train carrying over 600 passengers headed out of Newcastle Central Station hauled by two Ivatt 4MTs, Nos. 43000 and 43063, with the destination of the tiny Northumberland village of Woodburn.

This was the ‘Wansbeck Piper’ railtour – the final train to run over what remained of the Wansbeck Valley Railway, the last remnants of the incursion into Northumberland by Scotland’s North British Railway Company (NBR).

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

The beautiful county of Northumberland has in its past seen many skirmishes and battles between the English and their Scottish neighbours. Although peaceful for more than 200 years, a battle was to start again in the 1850s. This time however, it was between two rival railway companies – the North Eastern Railway (NER) based in York and the Edinburgh-based NBR. The Wansbeck Valley Railway was to find itself involved in the struggle between these two companies.

Origins of the Wansbeck Valley Railway

The NER had by acquisitions managed to obtain all the Anglo-Scottish traffic on the eastern side of the country in the form of the East Coast Main Line between Newcastle and Edinburgh via Berwick.

The NBR was far from happy with this and was desperate to get access into Newcastle and looked at all possible routes. The Border Counties Line from Riccarton Junction to Hexham had opened in 1856 to serve the North Tyne Valley and in 1862 this was taken over by the NBR.

This then gave the NBR a route from Edinburgh to Hexham via the Waverley route to Riccarton Junction and if it could acquire the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway, this would give the NBR a route into Newcastle. The NBR’s plans, however, were thwarted when the NER acquired the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway Company.

The NBR had also been focusing its attention on a proposal for a railway along the Wansbeck Valley from Reedsmouth, a junction on the Border Counties Line to Morpeth. If it could reach Morpeth and then acquire the independent and successful Blyth and Tyne Railway, this could then give it access into Newcastle.

Local inhabitants in the Wansbeck Valley had held a number of public meetings to obtain support and capital for the venture to construct a railway between Morpeth and Reedsmouth. The promoters called themselves the Wansbeck Valley Railway and included local land owner Sir Walter Trevelyan, owner of Wallington Hall near Scotsgap.

Sir Walter saw revenue coming to his estates by the supply of coal, limestone and agricultural products which would be transported by the railway to the growing markets on Tyneside. The promoters quickly found they had the support of the MP for Northumberland, Richard Hodgson, who surprisingly, was also the chairman of the NBR. The Wansbeck Valley Railway received the Act of Parliament in 1859 and construction work started immediately.

This started at Morpeth and the relatively easily constructed 11-mile section to Scotsgap was opened in July 1862. The more steeply graded and winding stretch over the wild Northumberland moors from Scotsgap to Woodburn and on to Reedsmouth took longer to build but was opened in May 1865, thus completing the 25-mile-long cross-country route.

From the opening of the first section of the route, the NBR was essentially operating the Wansbeck Valley Railway by supplying coaches and locomotives and it was only a few months after the opening of the complete route that the NBR took over full ownership.

With the support of the NBR in the form of Richard Hodgson MP, the railway promoters were also looking at opening further lines in Northumberland, which would give the NBR a slightly more direct route from Edinburgh. This would be the Northumberland Central Railway, running from Scotsgap to Rothbury then on to Wooler and finally Coldstream. At Coldstream, it linked up with the Berwick to St Boswells Railway, which joined the Waverley route to Edinburgh at St Boswells.

This proposal raised considerable concerns from the residents of Alnwick, supported by the Duke of Northumberland, who saw the prospect of Rothbury taking over from Alnwick as the agricultural railway centre of Northumberland. They pressed the NER to extend its short branch line, which ran from Alnmouth on the east coast route to Alnwick. They wanted this branch to be extended northwards to Wooler and on to Coldstream, where it would join the Berwick to St Boswells Railway. They considered this would ensure Alnwick remained the railway agricultural centre of Northumberland.

The NER succumbed to this pressure and the railway was constructed but it proved to be very uneconomic. The passenger service was withdrawn in September 1930 and the route closed in March 1953.

Richard Hodgson continued to press hard for the Northumberland Central Railway but finance was not forthcoming and all that was constructed was a branch from Scotsgap to Rothbury, which opened in 1870. To the dismay of the NBR, the NER finally acquired the Blyth and Tyne Railway in 1874 and this ended NBR’s hopes of ever getting access into Newcastle and thus ended the battle between the two arch rivals. This was then the final structure of the railway system in Northumberland and the system remained intact until just after the creation of British Railways (BR) in 1948.

Operations

The railways of central Northumberland were to provide a vital service to the inhabitants of the remote areas of the country but they were never money spinners. On the Wansbeck Valley Railway, freight traffic included limestone and coal but it was predominately agricultural traffic, particularly livestock from the large cattle markets at Scotsgap and Rothbury. There was also a considerable amount of military traffic to Woodburn – comprising troops, artillery and ammunition for the nearby military camp and firing ranges. At Knowesgate, the station just before Woodburn, horse-drawn artillery used to be unloaded before being taken to the firing ranges. Just beyond Woodburn, there was a short branch into a specialist test firing range, which allowed large guns to be transported by rail from Sir William Armstrong’s works at Scotswood on the River Tyne.

The passenger traffic on the Wansbeck Valley Line was always light and it was operated in two separate sections with normally three or four trains in each direction. Morpeth to Rothbury was one section and in the early years of operation trains would originate at Tynemouth or Blyth, running to Morpeth and then continuing on to Scotsgap and Rothbury. At Rothbury there was a small engine shed, a sub shed of South Blyth. There was also a turntable, where the locomotive could be turned for the run back to Morpeth.

The second section of the line was from Scotsgap to Woodburn and continuing on to Reedsmouth Junction. A turntable at Scotsgap allowed the locomotive working this section from Reedsmouth to be turned. The locomotives used on this part of the Wansbeck Valley Railway were housed in a small shed at Reedsmouth, a sub shed of Blaydon. In the later years of operation, the shed at Rothbury would be allocated a J21 0-6-0 and a G5 0-4-4T, while Reedsmouth would be allocated two J21s.

Downturn

Not long after nationalisation, the newly formed BR was quick to take action on the very uneconomic rural railways of Northumberland. The locomotive sheds at Reedsmouth and Rothbury were closed on August 12, 1952 and then exactly one-month later, passenger services were withdrawn between Scotsgap and Rothbury, with G5 0-4-4T No. 67341 working the last train. The main section of the Wansbeck Valley Line between Morpeth, Scotsgap and Reedsmouth then closed to passengers two days later.

The Border Counties line lasted a little longer, but passenger services were withdrawn on October 13, 1956. The last passenger train between Hexham, Reedsmouth, Riccarton and Hawick was worked by Blaydon’s K1 2-6-0 No. 62022. Freight services continued a little longer, but these were also slowly severed. The Border Counties line closed completely on August 22, 1958 when freight services were withdrawn between Hexham and Riccarton Junction. On the Wansbeck Valley line, the sections between Woodburn and Reedsmouth and those between Scotsgap and Rothbury were closed on November 8, 1963.

The last train on the Scotsgap to Rothbury section ran on the next day – this was RCTS (Railway Correspondence and Travel Society)/SLS (Stephenson Locomotive Society) ‘Wansbeck Wanderer’ hauled by Ivatt 4MT 2-6-0 No. 43129. As a result of this, the only surviving section of the Wansbeck Valley Railway was the stretch from Morpeth to Scotsgap and Woodburn. This then became the final remnants of the NBR’s routes in Northumberland.

This section only survived because of the large Army camps at Woodburn and Otterburn. In the summer months, Army specials would convey troops and equipment to Woodburn and throughout the remainder of the year a Thursday only freight to Woodburn would bring in stores for the camps and coal for a coal depot at the station.

This continued for a further three years until the Army decided troops and equipment could be moved by road, spelling the death knell for the railway. On September 22, 1966, the final Thursday freight ran from Morpeth to Woodburn. South Blyth’s J27 No. 65842 had been specially cleaned up for the occasion and the train, comprising of eight waggons and a brake van, arrived at Woodburn in beautiful autumn sunshine.

An article in the local newspaper reported the event and the reporter who travelled in the brake van interviewed the crew, comprising of driver Norman Mason and fireman Ray Howe, both from Blyth. Norman Mason said: “It’s a lovely run. We do it on a once in 20-week rota. It’s a change from the rat race and we take our time.”

Although passenger services ended on the Wansbeck Valley Line in 1952, the route continued to see occasional passenger specials, some for the Bellingham Agricultural Show near Reedsmouth. The organisation which ran some of these specials was the Gosforth Round Table – its first special was named the ‘Bellingham Belle’ which ran in September 1964.

This was a DMU from Newcastle to Morpeth and then on to Woodburn. Special buses then transferred the 350 travellers from Woodburn to the agricultural show at Bellingham. This was such a success that it was repeated a year later when the capacity was increased to 418 passengers, with buses provided to take the passengers either to the agricultural show or on to Kielder.

The events were so successful that the Gosforth Round Table thought it could become a regular annual event. However, this idea was crushed when in the summer of 1966 BR announced the line would close in the autumn due to the cessation of military traffic.

‘The Wansbeck Piper’: Wansbeck Valley Railway’s final train

The Gosforth Round Table quickly decided to run two final specials on the route – one would be another ‘Bellingham Belle’ and then there would be a final train on the route, this would be called ‘The Wansbeck Piper’. Sadly, the final ‘Bellingham Belle’ had to be cancelled as an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease broke out in Northumberland. All efforts were then transferred to ‘The Wansbeck Piper’ and as this was to be the final train, was there a possibility this could be steam-hauled instead of the previous DMUs?

Much to the organisation’s delight, BR agreed to provide two Ivatt 4MTs from North Blyth depot. Once advertised, the round table team was staggered at the public response – demand for tickets was overwhelming. The train was extended to 11 coaches, including a buffet car after 640 tickets were sold. A further 500 requests had to be turned down. With the 11 coaches and two Ivatt 4MTs at the front, this final train was to become the longest train ever to travel along the Wansbeck Valley Line.

I had just returned to my school in Blyth after the summer holidays when Jim Scott, the teacher who ran the school railway club, asked my friend and I whether we would be interested in a steam-hauled tour from Newcastle to Woodburn.

In the winter months of the early Sixties, from my home garden, I would see J21 No. 65033 (now under restoration by The Locomotive Conservation and Learning Trust), with snow plough fitted, travelling from South Blyth Depot to undertake snow clearance duties on the Wansbeck Valley line. I never imagined that one day I would have an opportunity to travel on the route. Jim Scott had acquired four tickets. He had two spare, so we both jumped at the opportunity and paid the pricey sum of 18 shillings and six pence for a ticket.

October 2 arrived and we set off from Blyth to Newcastle Central Station, where we met the fourth member of our group. We were surprised to find it was Alderman Jack Curry, the mayor of our home town of Blyth. At 1.40pm, the empty stock arrived into Newcastle Central to be greeted by 640 excited travellers. North Blyth had prepared Ivatt 4MT Nos. 43000 and 43063, which were to run coupled tender to tender and it was No. 43063 that was leading No. 43000 and the empty stock into Platform 9. North Blyth had made an excellent job of painting and cleaning up the two locomotives.

However, I was later to learn that after all the work the North Blyth men were very disappointed that they had not been asked to crew up the locomotives – this had instead been given to Heaton men. It was very sad as the Blyth Sheds, particularly South Blyth, had always provided the locomotives and crews for the Wansbeck Valley route.

After the two locomotives ran around the train, it was No. 43000 that was on the front, the first of the class of 162 LMS Ivatt 4MTs. Alderman Curry was ushered to the front of the train and proudly climbed up onto the front buffer beam of No. 43000 to affix the headboard ‘The Wansbeck Piper’ onto the smokebox front.

During the journey, I was to discover Jack Curry was a lifelong railwayman and had worked as a guard on the Wansbeck Valley line for many years. One of his recollections was of the severe winter of 1963 when a J21 got stuck in snow drifts and another locomotive was sent to help and this also got into difficulties and ended up stuck, both locomotives having to be abandoned until the snow thawed.

Outward trip

At 1.55pm, we set off from Newcastle, Jim Scott had a tape recorder with a number of blank tapes so he could record the full journey and play it back at our School Railway Club meetings. Passing over the famous diamond crossing, the two Ivatts opened up, once through Manors station we were soon roaring along the East Coast Main Line. On past Heaton depot and the carriage sheds, and then on to Cramlington, where in 1926 the ‘Flying Scotsman’ was derailed by strikers.

Morpeth was quickly reached and as we slowed down for the tight right-hand curve leading into the station, I got my first sight of the Wansbeck Valley Line or ‘The Wannie Line’ as it was affectionately known, trailing in on our left-hand side. The train stopped in the loop just north of the station to allow the two locomotives to run around.

We departed Morpeth at 2.40pm with No. 43063 now the leading locomotive. I was fortunate to find a vacant carriage door window from which I could put my head out and listen to the sound of the two Ivatts climbing the 1-in-95 out of Morpeth. It was then on past the derelict remains of Meldon station with its overgrown sidings, before the first stop was made at Angerton station.

With the long length of the train and the short platforms, only certain coaches could be exited at the stations. I found one and got out onto the platform, but it was virtually impossible to get a photograph of the locomotives due to all the people milling around, which I was to discover, would be the case at every stop made.

The leading engine was beyond the level crossing gates, which had to remain closed throughout the period the train was stopped in the station. What I did get my eye on was an NBR relic; unbelievably it was an NBR ‘Warning to Trespassers Notice’ beside the crossing gates. It was then a hoot on the whistle and everyone clambered back on board and then we were off.

Again, there were superb sounds as the locomotives set off on the four-mile climb of 1-in-67 to Scotsgap, the next station on the route. As we entered the Scotsgap station, I could see the large cattle market on the right-hand side, which years before provided considerable traffic for the line. Scotsgap was a longer stop to allow the two locomotives to take on water from the only water tanks on the ‘Wannie Line’. The tanks were situated just below a road over bridge which was crowded with people trying to get a view of our train and the locomotives. On the opposite side of the line to the water tanks was a very rusty turntable. This was the one that had been used to turn the locomotive that worked the passenger service section from Reedsmouth to Scotsgap.

After a 20-minute stop, we were off again, passing on our right the remains of the branch to Rothbury. It was then another three miles of climbing to the next station, Knowesgate.

Throughout this section, the line was continually twisting around the contours of the hills. This was the section that Jack Curry recalled the J21 and snow plough getting stuck in severe drifts during the winter of 1963. Even though I was concentrating on the sounds of the locomotives, I could hear in the background the sounds of the Northumbrian Pipes. Jack Armstrong, piper to the Duke of Northumberland and a lady piper, Patricia Jennings, were slowly making their way through the train, playing these lovely mellow sounding pipes to an appreciative audience as the train travelled through the beautiful Northumberland countryside.

A brief stop was made at Knowesgate where the loading bay, together with an old crane, still remained, presumably this was where the horse drawn artillery used to be offloaded. Suddenly, as if in a fitting tribute, the clouds dispersed and the sun came out to highlight the beautiful autumn colours.

We were now climbing over the wild moors where the heather bushes came right down to the lineside. To the left I could see the jagged crags of Hepple Heugh and Great Wannie, known as ‘The Wild Wannies’ from which the line was given the name of ‘The Wannie Line’.

On the right we passed Summit Cottages with their snow protection fences made of sleepers, which at 800ft above sea level were the highest point on the line. We then slowed to a halt as a group of sheep were walking along the track, I was told this was a common occurrence on the route. The driver made a quick blast of steam from the cylinder drain cocks of No. 43063 and they hurried off, allowing the train to restart and make the slow descent into Woodburn station.

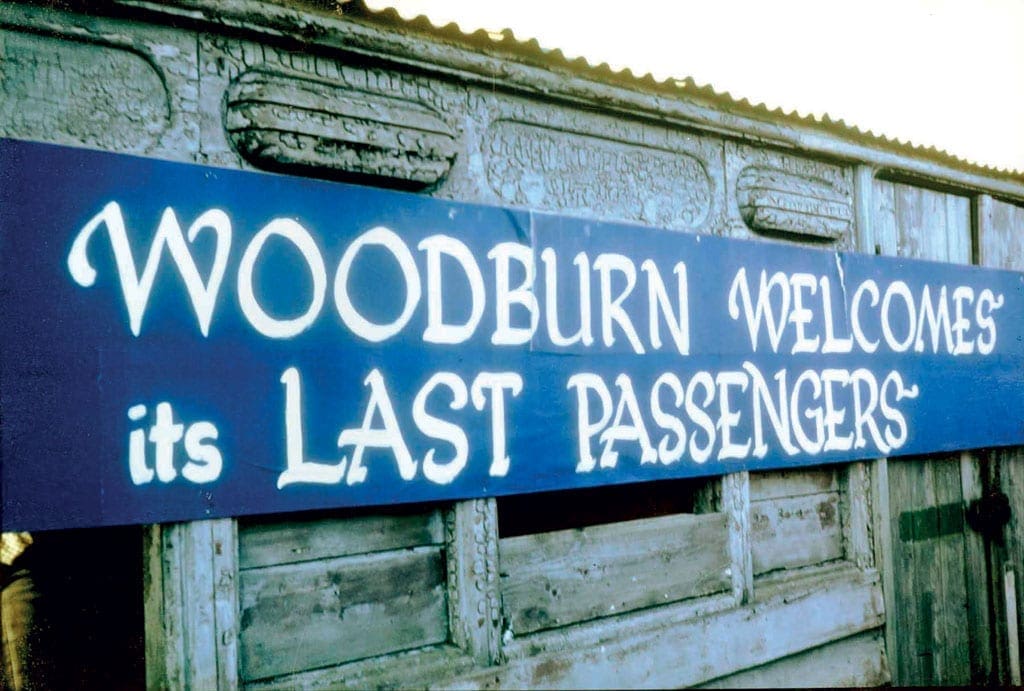

I quickly got off the train at Woodburn to get some photographs of the two Ivatts. It was not easy as they had stopped in a steep cutting just beyond the road bridge, which carried the A68 from Newcastle to Jedburgh and was next to the Woodburn home signal. It was here, at the 22-mile post, that the buffer stops had been positioned following the closure of the three-mile section from Woodburn to Reedsmouth.

The position of the buffers also meant there was only sufficient room for one locomotive at a time to move forward, then reverse back and run around the train. Again, it was almost impossible to get a clear view of the locomotives with the passengers from the train and the local residents all trying to see and take photographs of this sad occasion.

All possible vantage points were being used, particularly the old NBR signals, which would never have experienced so many photographers climbing up them – fortunately, none of them fell off! The stop at Woodburn was very short, only 25 minutes, so I concentrated on trying to get some photographs instead of watching the official closing ceremony.

This ceremony involved the planting of a commemorative tree by Major and Mrs F J Charlton of Hesleyside, near Bellingham. It was Major Charlton’s great grandfather who had been involved in pushing ahead with the construction of the railway, despite some opposition. Among his family heirlooms were two of the original spades used for the construction of the railway and these were being used for the tree planting.

In addition, a presentation was made by the Gosforth Round Table to their hosts at Woodburn, the stationmaster and his wife, Mr and Mrs Burgess Jefferson.

Last leg

The 25-minute stop passed very quickly and all too soon I heard the sound of the whistles summoning everyone to get back onto the train. In the background, a lone piper struck up a note – it was piper Joe Cain now playing the Scottish pipes in a final lament as the last Scottish line in England disappeared forever.

With everyone back on board and with the engines whistling, the ‘Wansbeck Piper’ set off on its return journey. With their huge load, the two Ivatts made a superb noise as they set off on the three-mile climb of 1-in-62 with the sounds of the Scottish pipes playing in the background. There was a momentary slip by one of the locomotives, then the deafening sounds of exploding fog detonators which had been placed on the track. There was a short acknowledging whistle from the locomotives and then another huge deluge of exploding detonators followed by a final long wailing whistle which served as the final farewell to Woodburn.

It was then just the sound of the crisp exhausts from the two locomotives as their full tractive effort was employed to tackle the long ascent to the summit. First ‘as one’ and then ‘hunting’ the exhaust note sounded through the open coach windows as the two locomotives climbed their way out of Woodburn. Jim Scott was concentrating on recording the superb sound effects as I found an unoccupied window from which to get some photographs. The lighting was now superb, with beautiful sunshine beating down on the train as the two locomotives struggled with their heavy load. I could see a number of photographers on the hillsides obtaining what must have been superb photographs of the train climbing out of Woodburn.

Eventually on reaching summit cottages and the end of the climb, the locomotive regulators were closed and the superb exhaust note stopped. The Northumbrian countryside around Woodburn settled down again to peace and quiet, marking the end of a route which first began more than 100 years ago.

We soon arrived back into Morpeth where the locomotives again ran around the train and then we were quickly tearing along the East Coast Main Line. Arriving back into Newcastle station at 6.35pm, it had been a superb afternoon which had passed far too quickly and my memories of the sights and sounds of that sad day have remained with me to this day.