By Scott Damant, General Manager’s Office, Great Eastern Railway.

First published November 1899.

IN an interesting article which appeared in The Daily Telegraph on August 8th last, the author, after graphically describing the scenes enacted at the various London termini on the preceding Bank Holiday said, “But at Liverpool Street is to be seen the most impressive illustration of the vast efflux from London. Let the man who has never witnessed it go on a Bank Holiday morning to the iron foot-bridge that spans its score or so of plat-forms, and he will never forget the spectacle. Below is a crowd which must at any time of the day run into thousands, flowing in obedience to ubiquitous placards and direction boards towards the various starting points, while the stout bridge itself vibrates and sways under the ceaseless stream which flows over it.”

The description is an accurate one, except, perhaps, with regard to the alleged swaying of the footbridge. On the day in question, 40,300 tickets were issued at Liverpool Street. Of course that number by no means represents all the traffic dealt with at the station ; many who journeyed that day had taken the precaution to procure their tickets beforehand at one of the many London booking-offices, and the up traffic was not to be despised, for just as the tired cockney hies him forth to the country or the seaside upon a Bank holiday, so his country cousins come in goodly numbers to the great metropolis.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

The average amount of work performed at the station can better be gauged by taking the number of passengers passing through it on a normal day. Such a day was Tuesday October 18th, 1898, when very careful countings were made. It was then found that 67,210 persons arrived at the station, and 69,335 left. Thus in all, 136,545 passengers made use of it during the day, or, to speak accurately, day and night, for it must be borne in mind that Liverpool Street is open for the entire twenty-four hours, except for a short time early on Sunday mornings.

“Porter, what time does the last train go to Walthamstow?”

“Lor’ bless you marm, there aint no last train to Walthamstow.”

This gem of “ English as she is spoke,” overheard late one evening near the barrier of N0. 3 platform, describes the state of affairs with admirable accuracy if due allowance be made for a redundancy of negatives.

Therein lies the initial difficulty in describing the day’s work at Liverpool Street Station; it is not a day’s work of twelve hours, but one of twenty-four hours, and the point arises where to begin. The time-tables start at 1.0 a.m.; but, taken all round for the purposes of this article, it would appear better to start at two minutes after midnight, “an hour when all good little boys and girls should be in bed; ” and, if it comes to that, their parents also.

12.2 a.m. has been selected because then the earliest train leaves for Chingford, and all stations on the way thereto. It is well filled with those who have been to theatres and other places of amusement, or “detained late at the office, my dear.” Equally full are the 12.10 to Palace Gates (Wood Green), the 12.15 to Snaresbrook, the 12.20 to Romlord, and the 12.25 to Enfield Town. Three minutes after the departure of the last-named train the last train from Chingford arrives. One may call it the last train, not the first train, because although it arrives at Liverpool Street at 12.28 a.m., it leaves Chingford at 11.55 p.m. the previous day. Then it returns to Wood Street, Walthamstow, after a four minutes stay at Liverpool Street, passing, between Hackney Downs and Clapton, the first train from Wood Street, which leaves that place at 12.34 and arrives at Liverpool Street at 12.58. Thenceforward for four hours two trains an hour journey either way between Liverpool Street and Walthamstow.

The question is often asked by officials of other Companies, by journalists, and by those of an enquiring mind generally, Does this all-night service pay?” This is one of those questions much easier to ask than to answer. Probably it will be some time before the service pays directly, but there is always an indirect profit as well as a direct profit to be reckoned with when considering whether any given travelling facility offered by a Railway Company to the public actually pays the Company. In this case it is known that the all-night service is greatly appreciated by a large number of newspaper men, persons employed in the various cattle, meat, fish and vegetable markets, and others whose avocations necessitate their working when the rest of London sleeps. Now, many such have undoubtedly moved into the Hackney and Walthamstow districts in consequence of this service, and have taken season tickets; but, as it is impossible to earmark the season tickets, the exact number cannot be ascertained. Then such men have not, as a rule, moved singly; they have brought wives and families with them who travel more or less during normal hours. Moreover, the additional families who have thus moved into the district all help to add to the building operations constantly going on; and, as Sir William Birt has more than once pointed out, they do not live on air. Their food, and the thousand and one necessities of more or less civilised life, are carried by the Railway Company; so that the indirect profit derived from the service may well be fairly considerable. But the direct return is not to be gainsaid. Thus the service commenced at Mid-summer 1897, and during the six months ending December 31st of that year, the total number of tickets issued for use by these trains was 160,834. For the six months ending June 30th, 1898, the number was 194,045, and for the six months ending lune 30th of this year the number had risen to 234,855. Of course, in estimating the profit, it must be borne in mind that the bulk of the passengers using this service travels third class, using “half fare tickets,”with a minimum charge of fourpence.

The monotonous arrival of trains to and from Walthamstow is broken by the getting in and out of certain goods trains. “ What ! goods trains in Liverpool Street Station!” the reader may well exclaim ; and their existence is, indeed, anomalous. The trains in question are those to and from the East London line, and till the completion of the hoist now in process of erection at Spitalfields, goods from the Great Eastern district for the South Eastern, Chatham and Dover, and Brighton lines, or vice versa, have to be taken into Liverpool Street, and thence out again on to the East London line. The process only takes a few minutes, but it is to be deprecated, and, although the hoist is intended primarily for coal, it will be also available for general goods traffic, and on its completion, which should take place very shortly after this article appears, the partial user of a purely passenger station for goods traffic will practically, if not entirely, cease.

At 3a.m. some diversion is caused by the arrival of the mail train from Yarmouth, Lowestoft, Cromer and Norwich, and a little stream of heavy-eyed passengers is generally to be observed ascending the stairs leading to the hotel. This mail train travels by a somewhat unusual route. Of course the direct route from the places named is via Ipswich, Colchester, Stratford, and Bethnal Green: but there is the alternative route, via Wymondham, Thetford, Ely, Cambridge,

Tottenham, Clapton, and Bethnal Green. This train does not exactly take either route, but travels via the Cambridge line as far as Tottenham, continuing eastwards over that line, so little used for passenger traffic, through Lea Bridge to Stratford (the main line of the Northern and Eastern Railway), proceeds thence to London on the Colchester line. Time was when that was the recognised route from the Cambridge line to London; but since the line through Clapton has been built, with its connecting loop with the Tottenham and Stratford line, the number of trains so travelling have been gradually lessened, and now they are few and far between.

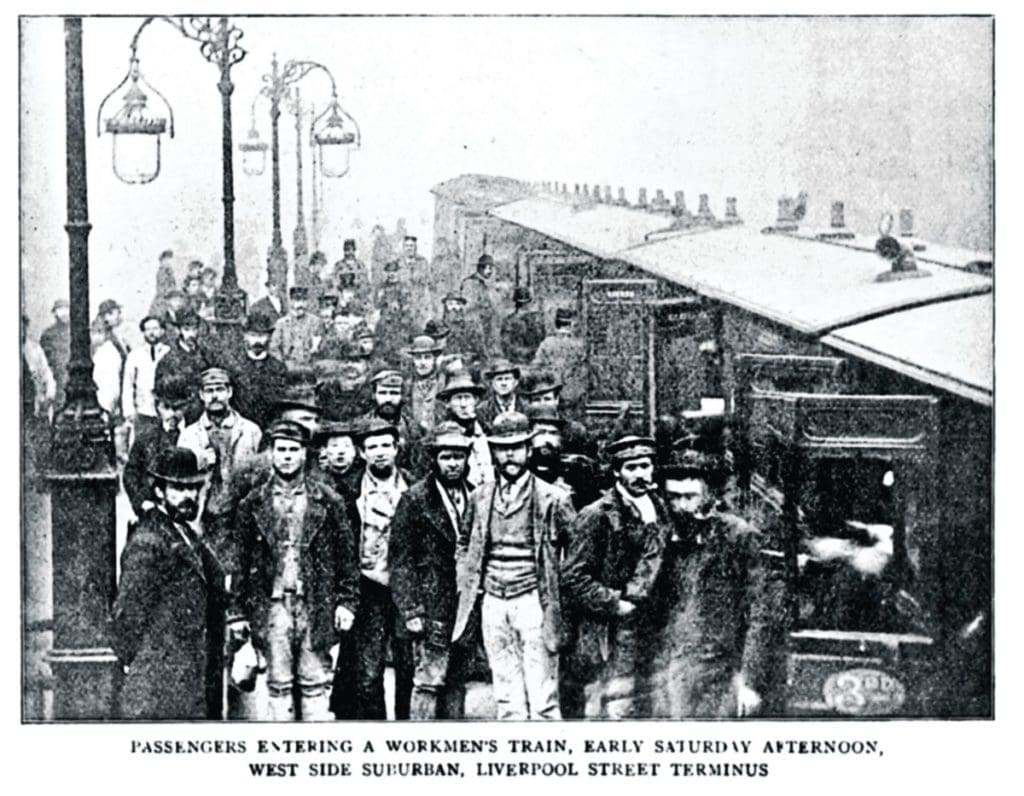

At 3.50 the Ipswich mail arrives, and then, at 4.43, a half-fare train from Enfield comes in. It returns to Enfield at 4.50; a train from Walthamstow arrives at 4.58, and leaves at 5.6, and then, 19 minutes after that time, the first “Twopenny train” from Enfield steams in. Then follows a succession of workmen’s trains, by which a uniform fare of twopence for the return journey is charged from Enfield, Edmonton, Walthamstow, and stations intermediate between those places and‘ London. Altogether twenty such trains are run, not to mention twelve more from Stratford and Stratford Market. These trains are nearly all packed, as might be expected, and the sight of the crowds of workmen and workwomen elbowing their way through the barriers, once seen, is never likely to be forgotten. It is absolutely unique. No other railway station can show a sight approaching it, which fact is probably viewed by the authorities responsible for working the traffic of other stations with wonderful resignation.

It is now over thirty years ago, since, after the lowering of the franchise, Robert Lowe gave vent to his famous dictum: “We must educate our masters.” Since then it has been ordained that “our masters” should be educated free, gratis and for nothing, at the expense of the ratepayers. But the generous magnanimity of our lawgivers has not stopped there. To judge from recent legislation, railway companies will soon be compelled to convey “our masters” on the same remunerative terms; indeed, if the utterances of certain labour leaders and the vapourings of a section of the press be heeded, the end will not be reached until the bloated and blood-sucking railways are compelled to pay a handsome royalty per head for the honour and privilege of being permitted to carry such of the horny—handed sons of toil as condescend to use the rail.

Until July 1st last the twopenny trains were followed by half-fare trains ; but the Railway Commissioners, in their wisdom, recently decreed that threepenny trains should be sandwiched in between the twopenny and half-fare trains. This was done to the extent of seven trains; and from October 2nd a further extension of these threepenny trains has taken place. In order to cope with the ever-increasing workmen’s traffic, new coaches have been lately designed and built by Mr.Holden, which seat six passengers on either side. The last half-fare train arrives at 7.59, and thenceforward for a couple of hours train after train steams in, laden with the vast Army of the Uncomplaining, the hordes of city clerks. No doubt they are all engaged in “keeping up appearances,” but at least they are pleasanter to deal with than their working-men predecessors, for they do not smoke foul cutties and they do not spit.

Before leaving the subject of the morning arrivals, mention should be made of the two Continental expresses, the one from Antwerp being due in at 7.35, and that from the Hook at 8.10. The scene during the Customs’ examination is an animated one ; there is much hand-shaking and kissing amongst old friends long parted, and the embracing is not confined to the sterner sex; bearded foreigners hug and kiss one another with an apparent appreciation of the odour of cheap tobacco and garlic. Similar in some respects, and yet in direct contrast to the foregoing, is the scene enacted when the “P. and 0. Special” leaves Liverpool Street for Tilbury. Then we stay-at-homes may obtain some faint, far-away notion of what our Indian Empire is. There are middle-aged sun-burnt officers and liver-cursed civilians going back to their duties; young subalterns, about to join their regiments, saying farewell to fond mothers and sisters; wives and children going back to join husbands and fathers; calm, impassive orientals, fez-topped or turban crowned, and brightly-attired ayahs, crooning some old-world heathen lullaby to the young Christians in their charge.

But we are getting somewhat out of chronological order. The first important main line train to leave the station is the 8.40 fast train to York; there are several earlier main line trains, but they do not call for special comment. The 8.40 is followed by the 9.0a.m. slow to Ipswich, the 9.42 to Cromer, and the 10.15 to Yarmouth and Lowestoft. This latter is always a very well-patronised train, taking just over three hours on the journey. It is followed by the 10.20 train which serves many places en route, has connections with all the smaller seaside towns, and finally steams into Yarmouth 55 minutes after its immediate predecessor. At 11.0 another fast train leaves on the Cambridge line. This is probably the train most used by passengers travelling by the Cathedral Route to the North, although the 4.30 p.m. takes six minutes less on the journey to York, and does the trip to Cambridge in one hour and thirteen minutes.

At 11.22 the Restaurant train arrives from Cromer, followed ten minutes later by that from Yarmouth. On Mondays two Restaurant trains precede these at 9.41 and 10.45 from Clacton and Cromer respectively. The success of these trains carrying first and third class Restaurant cars has been undoubted. Instead of an early, hurried, and unsatisfactory meal at the seaside, passengers now breakfast at ease en route. Equally appreciated are the Table d’hote dinners served on the 4.55 and 5.0 p.m. trains to Cromer and Yarmouth respectively. On Saturdays, luncheon is served on the 1.30 express to Cromer. This train is the most popular one to Cromer throughout the summer. It only stops once on the way, at North Walsham, for the convenience of Mundesley passengers, and does the journey to Cromer in two hours and fifty-five minutes. During the winter months it stops at Ipswich and Norwich, and of course takes longer on the journey. Perhaps it is as well to remark that, unless otherwise specified, the times given throughout this article are those in force during the summer months. In October considerable modifications take place, and in November the winter service proper commences.

Apart from the trains already referred to, there are one or two other important trains leaving the station of an afternoon, but towards the end of the season more life and bustle is to be seen at the arrival platforms, especially when the 1.0 p.m. express from Cromer, the 1.45 from Norwich, the 1.45 from Lowestoft, and the 2.10 from Yarmouth come in. These trains arrive at 3.55, 4.18, 4.33, and 5.0 p.m. respectively. The amount of luggage carried by these trains is phenomenal, for although many passengers avail themselves of the cheap charge for luggage in advance, others, elephant like, prefer to carry their trunks with them. Then there are the bicycles to be considered; over 1,300 have been dealt with at Liverpool Street in a single day. The amount of labour entailed in getting such a number of machines in and out of the trains can only be appreciated by those who have practical experience of working a railway. Mention the word “bicycle” and the habitual smile momentarily leaves the face of Mr. Randall, the station master at Liverpool Street. Breathe the same awful word into the ear of Mr. Keary, the assistant station master, and he “wears a worried look.” He is, however, better off than his famous prototype of the song, whose clothes having been stolen whilst he was bathing, had nothing else to wear. Mr. Keary has a gold braided cap to wear, and very nice he looks in it.

At about 4.0 o’clock the daily exodus from the city commences. holders of workmen’s tickets are allowed to travel home by any train between 12.0 noon and 4.25, but thenceforward they are restricted to certain specified trains until 8.55 after which time they may use any train that is booked to call at the stations from which they started in the morning. Some few of the return workmen’s trains only carry third class coaches. The last train to Norwich, Yarmouth, and other seaside places, via Ipswich, leaves at 7.15, but there is a train to Norwich and Yarmouth via Cambridge as late as 10.2. This is the mail train, and lands its passengers at Yarmouth at 3.0 a.m. the following morning, so anyone desirous of enjoying a nice long day at that salubrious watering place is certainly in a position to do so.

Of course the two most important trains of an evening are those conveying passengers to the Continent, the 8.30 in connection with the boat to the Hook of Holland and Rotterdam, which conveys Her Majesty’s mails to the principal stations in Holland, and the 8.40 in connection with the boat to Antwerp. After 10.0 o’clock nearly all the outgoing and incoming trains journey to and from the suburban district, the latest to leave being the 11.56 to Enfield, and the latest to arrive the 11.18 from Romford, which gets to town just a minute before midnight.

Altogether during the summer months this year 556 trains have left Liverpool Street during the twenty-four hours, and 547 have arrived. These figures, of course, do not include “specials.” During the winter months the number was 525 and and 512 respectively. The number of men employed to cope with this heavy traffic, who are under the control of the stationmaster, is over 300.

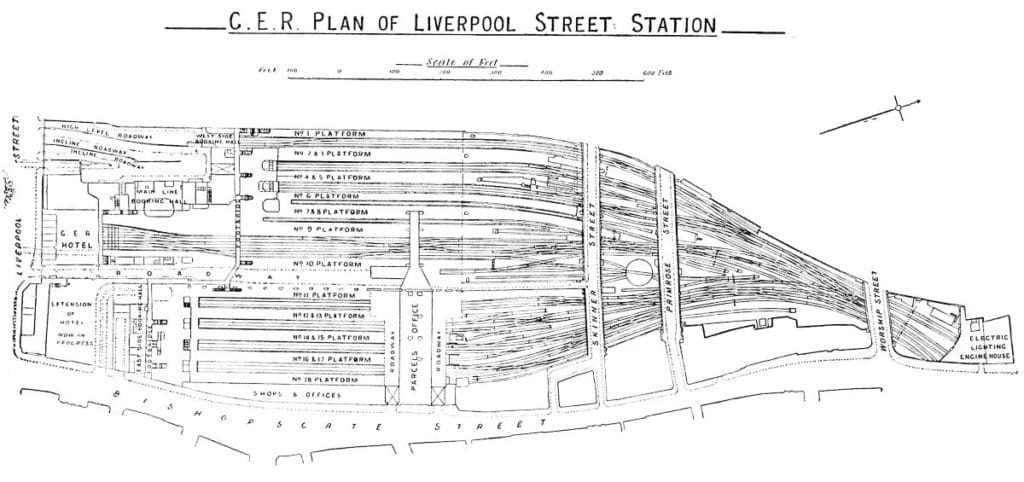

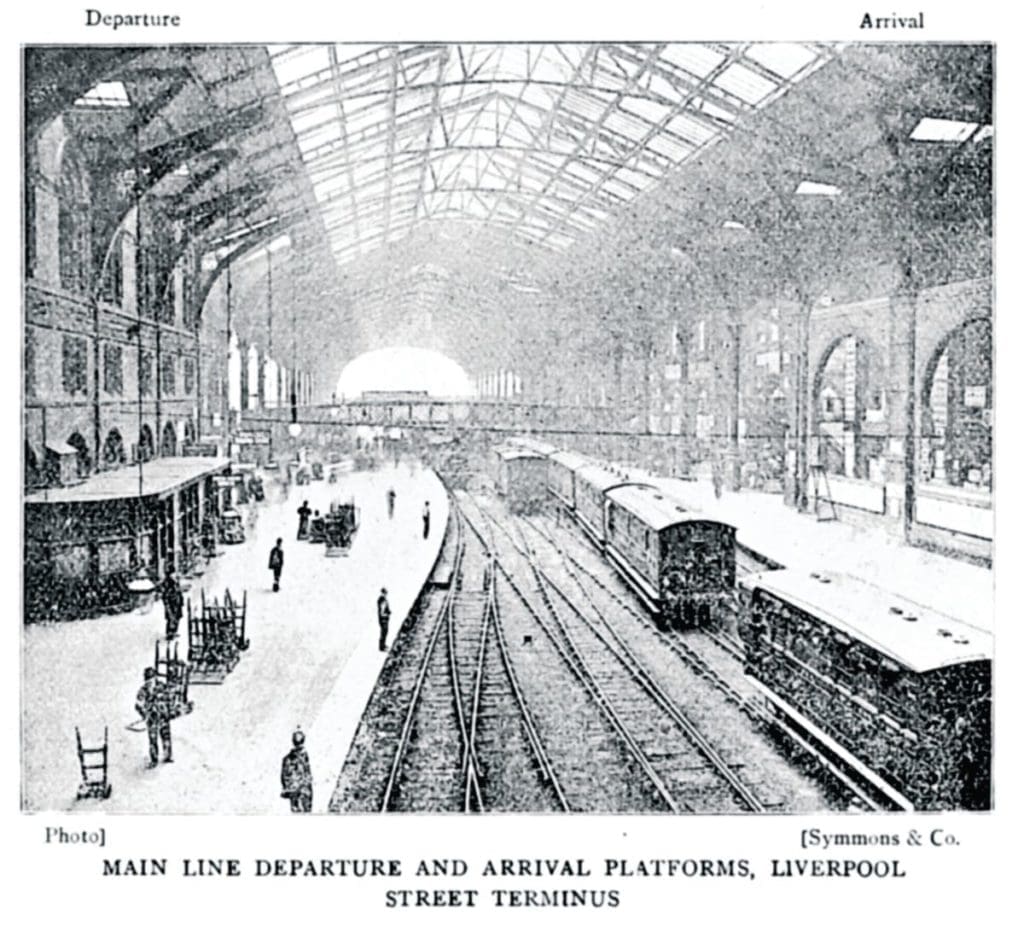

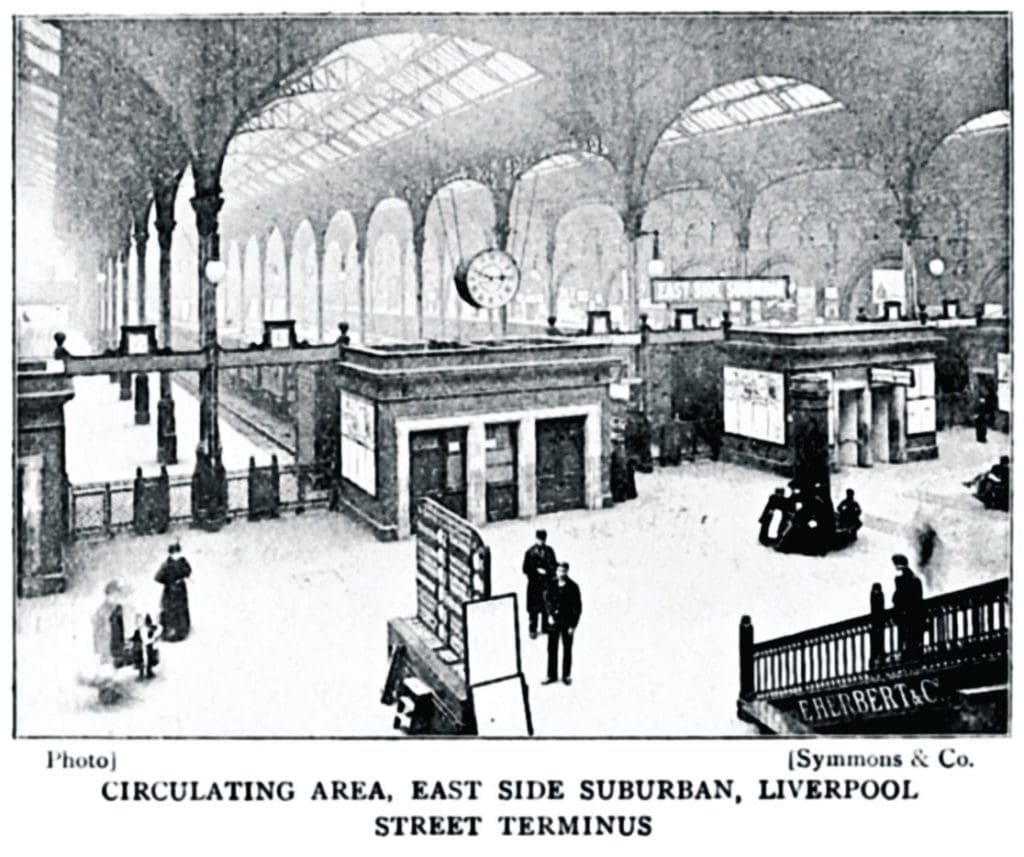

As stated in the RAILWAY MAGAZINE last December, Liverpool Street Station was opened for traffic on the 2nd of February 1874. The portion then opened is now known as the West Side. The other portion of the station, which was opened on the 1st of April 1894, is known as the East Side. The area of the West Side and approaches is 9 a. 3 r. 10 p., and of the East Side 6 a. 1 r. 9 p.

In order to build the East Side, no less than 150,000 cubic yards of earthwork had to be excavated, 10,715 cubic yards of brickwork being used. There are 20 “roads” and 18 platforms in the entire station, the area of the latter being, on the West Side 105,703 sq. ft., and on the East Side 65,425 sq. ft., and the length 7,610 and 4,380 lineal ft. respectively. The area of the circulating space on the West Side is 16,016 sq. ft., and on the East Side 21,730 sq. ft.

Now to turn our thoughts heavenwards, or, at all events, skywards. The area of the roof on the West Side, measured flat, is 180,000 sq. ft. At its widest part, clear of the station buildings, it consists of four spans, measuring 45 ft., 109 ft. (space between central columns 5 ft.), 109ft., and 43 ft. respectively. There” is, in addition, a central transept. No less than 1,079 tons of cast iron and 1,460 tons of wrought iron are used in this roof. The East Side roof, measured fiat, has an area of 88,000 sq. ft., and consists of four spans, running longitudinally with the railway measuring 49 ft. 7 in., 42 ft. 3 1/2 in., 42 ft. 3 1/2, in., and 51 ft. 7 in. respectively, supported on cast iron columns, with a roof running cross-wise to the line over the circulating space of 88 ft. span. The weight of cast iron used in the East Side roof is 340 tons, and of wrought iron 1,235 tons.

On the East Side are large parcels sheds, occupying an area of 11,500 sq. ft., exclusive of 11,600 sq. ft. of roadways leading to them. These sheds are of a particularly substantial nature, as may be imagined when it is mentioned that the weight of cast ironwork in the sheds, substructure, and roadways is 634 tons and of wrought ironwork 1,496 tons.

The need of such accommodation is evidenced by the fact that during the twelve months ending July last 3,797,016 parcels were dealt with at Liverpool Street, exclusive of the enormous number sent as “luggage in advance.” The parcels sheds, which are situated over the lines on the East Side, are connected with the West Side by a subway and an overhead gallery, the subway, gallery, and sheds having hydraulic lifts from the various platforms. The plant for working the hydraulic power for these lifts and for the engine turntable, as well as other machinery at the station, is situated at the Bishopsgate Goods Station.

The station, offices, and hotel at Liverpool Street are, of course, lighted by electricity, as are the Bishopsgate and Bethnal Green Stations, the company’s generating station for all being situated within the “Liberty of Norton Folgate,” a portion of the metropolis which, although outside the city walls, and even beyond Bishopsgate Without, is yet under the jurisdiction of the City fathers.

The station is approached by six lines of way, which, as already stated, develop into twenty lines of way in the station, the whole being controlled and worked from two signal-boxes, having 136 and 240 levers respectively. The length of permanent way in the station yard is about 7 miles, there being close on 150 points and over 200 crossings.

Although not so handsome, from an architectural point of view, as St. Pancras, the “West End” terminus of Great Eastern trains, Liverpool Street Station, with its offices and its hotel, is decidedly imposing looking. After all, it has been designed chiefly for use, and the millions of travellers who have trodden its platforms during the twenty-five years of its existence witness to the fact that it has well served its main purpose.

But the very latest addition to Liverpool Street Station is of a distinctly artistic nature. This consists of a large clock, having four faces, which is suspended from the roof of the main line in such a manner that it can be seen from all parts of the station. It is worked entirely by electricity, on a plan devised by Mr. Hollins, the company’s electrical engineer, and a contributor to the Railway Magazine. In appearance it resembles what in certain ecclesiastical circles would be termed a pyx surmounted by a corona. In spite of its vast size, it is most chaste and elegant in design, and a standing proof, if such be needed, that the useful and ornamental may be advantageously combined, even in so utilitarian an institution as a great railway station.

If you enjoyed this archive article, there’s plenty more to be read in The Railway Magazine Archive.