A Twenty-year Retrospect by P. H. S. Martin, first published in The Railway Magazine in January 1953.

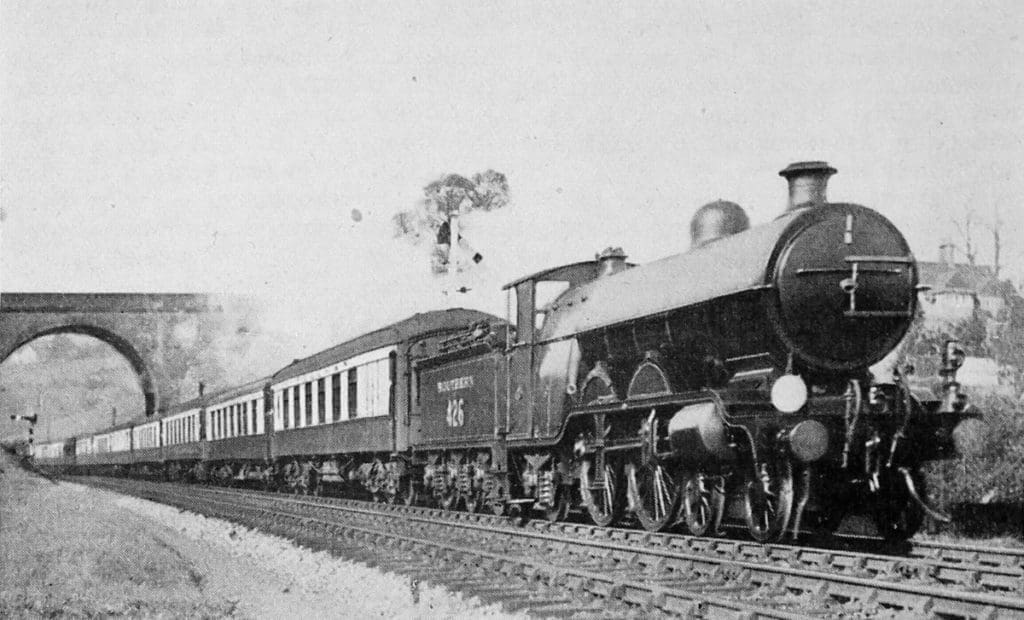

On July 17, 1932, the first stage (from London to Three Bridges) of the electrification of the Southern Railway main line between London and Brighton was opened to the public, and at 12.5 a.m. on New Year’s Day, 1933, the last steam operated passenger train left Victoria for Brighton. Today the electrified service which replaced the steam trains remains practically unaltered and is still a model of modern railway operation as well as an outstanding achievement of the “ grouping ” period of British railways.

In these days, we are inclined to think that life was easy before the second world war, but the early 1930s were difficult years in many ways. Hitler was not yet an obvious menace, but we were still suffering from the great slump, and had large numbers of unemployed. The railways, too, had their own problems in the enormous increase in competition from the new, fast, passenger coaches and private cars, which were crowding the newly-widened main roads. Nowhere was this competition more acute than in the 52 miles between London and Brighton, and good though the steam train service was, it was quite incapable of dealing with the new menaces. The distance was too short to show the superior speed of the train to advantage, and nothing but a fast intensive service would stand a hope of regaining the lost traffic.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

A scheme was prepared, and it was estimated that a very large number of additional passengers would be needed to justify the outlay of about £2 1/2 millions. To say that this target would be passed in a few years is being wise after the event. It was by no means obvious then, for the suburban area, although electrified, ended abruptly at Coulsdon, leaving about 35 miles of country main line, which, in the prevailing economic conditions seemed unlikely to yield much new residential traffic to add to whatever might be recaptured from the road. True there was rush hour traffic from Redhill, and Reigate, and a little from the Horley area, in addition to the long-established Brighton and South Coast business service. It was decided to proceed with the electrification avoiding all expenditure not absolutely necessary.

Track layout presented no great problems in the first ten miles out of London, as the service was to be divided between London Bridge and Victoria, from both of which four tracks, which had for years carried a heavy steam service, were available. At Windmill Bridge Junction, just north of East Croydon Station, these lines converged, and from this point the whole electrified service, and the steam trains to the Oxted line, Three Bridges, Horsham, Eastbourne and Newhaven had to be carried on four tracks, supplemented by a loop road as far as South Croydon.

It was decided to make no major alterations in the layout through the Croydon area as far as Coulsdon (15 miles from London) and this most interesting section still remains very much as it was when the original line was widened at the close of the nineteenth century. There was, however, some change in the use of the tracks, and several of the fast trains were routed over the suburban lines from Windmill Bridge, despite sharp curves and the blind entrance to East Croydon Station in the up direction. This practice, which is still followed, kept trains to and from the Quarry (fast) lines from conflicting with the trains using the Redhill, Tattenham, and Oxted lines.

At Coulsdon, the suburban lines ended, and the main line divided into two double tracks, which, while maintaining four-track facilities, followed different routes to Earlswood, 21 1/2 miles from London. The fast tracks had been the Quarry line of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, which reached Earlswood without intermediate stations, but with three tunnels, including an artificial one under the grounds of a mental asylum. The slow lines, with stations at Coulsdon South, Merstham, and Redhill, had belonged to the South Eastern & Chatham Railway until 1923, but had formed part of the original route to Brighton. It was decided to electrify this section, and to include the first 1 3/4 miles of the Reading branch, to cater for the Reigate traffic. Apart from some track alterations at Redhill, few changes were made on this stretch of line, which still has S.E.C.R. equipment in use.

From Earlswood to the entrance to Balcombe tunnel, a distance of ten miles, the four tracks laid down by the L.B.S.C.R. in the first years of the century were quite capable of carrying the new service, and apart from minor alterations no changes in the track were necessary. At Balcombe Tunnel, however, the four tracks converge into two and in the 19 miles from there to Preston Park, on the outskirts of Brighton, the line traversed four tunnels, three of which were of considerable length, and crossed the long viaduct over the Ouse Valley near Balcombe. Duplication was impossible by reason of the great cost which would be involved, but up and down loops were formed from Copyhold Junction, where the Horsted Keynes line diverted, to the station at Haywards Heath, which was reconstructed to give four through lines. Beyond the station the four tracks converged into two roads. At Preston Park four tracks were again available, and continued to the terminus at Brighton.

Unlike London Bridge and Victoria, Brighton Station had to deal with the entire new service, and had not been modernised to any extent, its layout remaining substantially that of 1881. Opportunity was taken to overhaul thoroughly the various tracks and connections, and to eliminate any which would not be needed for the electrified service. It had to be borne in mind, however, that a large number of steam-hauled trains from the coastal lines to Hastings and Portsmouth, and long-distance holiday traffic from the North and West, would continue to use the station. For the service envisaged, it was necessary to have short signal sections, particularly in or near the bottle neck between Balcombe and Preston Park. The existing installation, while adequate in the suburban area, was quite unable to cope with the new requirements on the remainder of the route. It was decided to equip the fast lines from Coulsdon, and all running tracks from Earlswood to the coast, with colour—light signalling, which, while largely automatic in operation, was controlled at junction points by new or modernised boxes with illuminated diagrams. There was, of course, continuous track circuiting, but the high cost of this equipment was offset to some extent by the fact that no less than 24 of the old boxes were abolished and nine others were open only at certain times, leaving no more than eight to control normal traffic between Couldson and Brighton. It is interesting to note that practically no alteration has been made in the installation in the succeeding 20 years.

In 1933, it was expected that the sections between London and Brighton still controlled by manual signalling would shortly be converted. Colour-light signals were introduced between Streatham Common and Thornton Heath in 1936, and the equipment at Victoria was modernised in 1939, but the remainder of the work had not been undertaken before the outbreak of the second world war. Despite present—day difficulties arising from re-armament and shortage of steel, colour-light signals are now being introduced in the suburban area between London and Coulsdon. The first stage of this programme, the section of the London Bridge line from Bricklayers Arms Junction to ‘Norwood Junction, was completed in October, 1950, and the second, extending from Battersea Park to Selhurst, on the Victoria line, in October, 1952. The scheme is due for completion in 1955.

In addition to the branch from the main line to Reigate, the electrification was also extended from Brighton westward along the coast as far as West Worthing, to encourage the residential and holiday traffic which had made substantial progress under the former L.B.S.C.R. By the summer of 1938, this had been extended to Portsmouth and the branches to Littlehampton and Bognor Regis as part of subsequent electrification schemes. East of Brighton, the lines to Eastbourne and Hastings were electrified in July, 1935.

The rolling stock for the Brighton electrification was entirely new, and consisted of two types of set trains: 23 six—coach corridor vestibule units, each comprising three compartment coaches, an open third-class motor coach at each end, and a composite Pullman car in the centre; and 33 four-coach compartment units for semi-fast and slow trains. In subsequent extensions of the main-line electrification, the types of rolling stock used for the Brighton trains were perpetuated with slight modifications, in that the express stock became a four-car unit with end vestibules, while the four-car non-vestibule units became units of two cars. Mention must be made of what has remained a unique feature, namely the three sets of five coaches built by the Pullman Car Company to operate the long established “Southern Belle” service (renamed the “ Brighton Belle” on June 29, 1934). These luxurious trains still operate the service, though one set was seriously damaged by enemy action, and had to be reconstructed after the war.

Some surprise was expressed that, as the stock was new, opportunity was not taken to adopt the open saloon type of coach throughout, but although the problem has been under frequent review, compartment coaches have been considered preferable for the traffic on this line. The fear also was expressed that the large unsprung weight of the motor bogies would cause heavy track maintenance and rough riding at high speed. Rough they certainly were at first, but this was reduced by detailed improvements through the years, and considering the speed and intensity of the service, track wear never seemed excessive.

The operation of the new services which provided one non-stop, two semi-fast, and two slow trains between London and Brighton every hour during the day, was in itself a major problem. The crucial section was the bottle-neck between Balcombe Tunnel and Preston Park, with its solitary loop at Haywards Heath, but there was the additional difficulty of interspersing the still considerable amount of steam-operated traffic. While the electric trains were capable of rapid acceleration and could be given a close schedule between points, the steam trains inevitably varied in length and accelerative power. In practice, the steam traffic was largely non-stop, and the electric service was arranged with departures at fixed times in each hour. Station stops were reduced to the shortest time possible, but there still remained a minimum of time required for a stopping train to clear the bottlenecks. This largely explained the complaint made at the time that the new non-stop trains were no faster than the steam trains of 30 years earlier.

In the first few weeks, enthusiastic drivers revelled in the 75 m.p.h. maximum speed possible with the new trains, only to find that by Burgess Hill or Hassocks they were getting a succession of “ yellows,” or perhaps even a dead stand, because they were overtaking the slow train in front, and had to continue treading on its heels until it escaped into the loop at Preston Park. The Southern Railway laid down the excellent principle of timetable construction, that times which could be kept under all normal circumstances were far better than a schedule which was possible only with a fair amount of luck.

Actually, the working time for the non-stop trains was 57 min., but the public time remained at 60 min., and is so today, though a considerable amount of the other traffic on this route is still steam operated. The Oxted lines are still not electrically equipped, and the only relief to steam operation of the Continental services to Newhaven is that given by the three electric locomotives, which also assist with the goods trains.

The effect of the introduction of so much new stock had some queer effects on the now redundant rolling stock. A few of the oldest locomotives in mainline service went to the scrap heap rather more rapidly than they might otherwise have done, but most of the locomotives found use elsewhere, though in some cases only for a few years until the Eastbourne lines were electrified. With the coaching stock, however, it was rather different, as most of the main-line services had been operated with coaches constructed in 1906 and 1907, and, by reason of their shape, usually known as “balloons.” Because of their extreme width and height, they could work only on certain lines of the old L.B.S.C.R. and they could not be used on the former London & South Western and South Eastern & Chatham Railways. Most of these coaches went to the scrap heap fairly soon after 1932, leaving less pretentious, but older, coaches to supply the needs of remaining steam passenger services until more modern steam stock became available from other parts of the system article.

No Consideration of this large scheme of electrification could be complete without mention of the staff involved. Drivers had to become accustomed to an entirely new technique of driving, while the extensive resignalling meant relearning what had been a familiar road. Station staffs had to remember that stops were now very short, and must be rigidly observed. The increased number of men needed for maintenance of lineside electrical equipment had to bear in mind that trains were frequent and speeds high. Many signalmen had either to learn a completely new signalling layout in the boxes to which they had been accustomed, or to master a new box. The fact that the changeover was accomplished smoothly was something of which all concerned could be proud. Such mistakes as were made were of minor importance and endangered no one. The “ Southern Belle ” was brought to a stand at Croydon on the second day because the yard shunter had not realised he must now make a quick crossover from the down side to the up. Two days later a non-stop train threaded its way slowly round the loop platform at Haywards Heath while a stopping train stood on the through road.

On a general survey of the whole installation, one is struck, not only by the large amount of existing equipment which was brought into the new scheme of 1932, but by the fact that much of it has since stood up to 20 years of intensive service for which it was never designed. It is all now long past the life for which it was designed, and would, in less difficult times, have been replaced many years ago. At the moment, however, it seems that, where possible, it may have to continue to carry the burden for years to come, although within the limits imposed by the national situation, substitution of more modern equipment will be made. The provision of a new signalbox at Three Bridges in 1952 is a sign that some of the L.B.S.C.R. equipment is now life- expired.

The writer is indebted to Mr. S. W. Smart, Superintendent of Operation, Southern Region, who was closely associated with the Brighton electrification, for assistance in the preparation of this article.