With its future currently uncertain, take a look back at this archive article from 2012 following the announcement that the government planned to go ahead with HS2. What has changed and what has stayed the same?

*Note: this article is presented as it appeared in the March 2012 issue of The Railway Magazine.

by Chris Milner and Nick Piggot

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

THE Government has given the green light to Britain’s second high-speed railway line, HS2. Construction will start in 2019 and the first leg of the route should be open between London and Birmingham by 2026.

It is only the second major railway to be built in Britain since completion of the Great Central in 1899.

Confirming the decision on January 10, Transport Secretary Justine Greening said that HS2 will be a Y-shaped network with stations in London, Birmingham, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield and the East Midlands linked by high-speed trains conveying up to 26,000 people an hour at speeds of up to 250mph. The trains will also connect seamlessly with existing West Coast and East Coast main lines to serve passengers beyond the HS2 network.

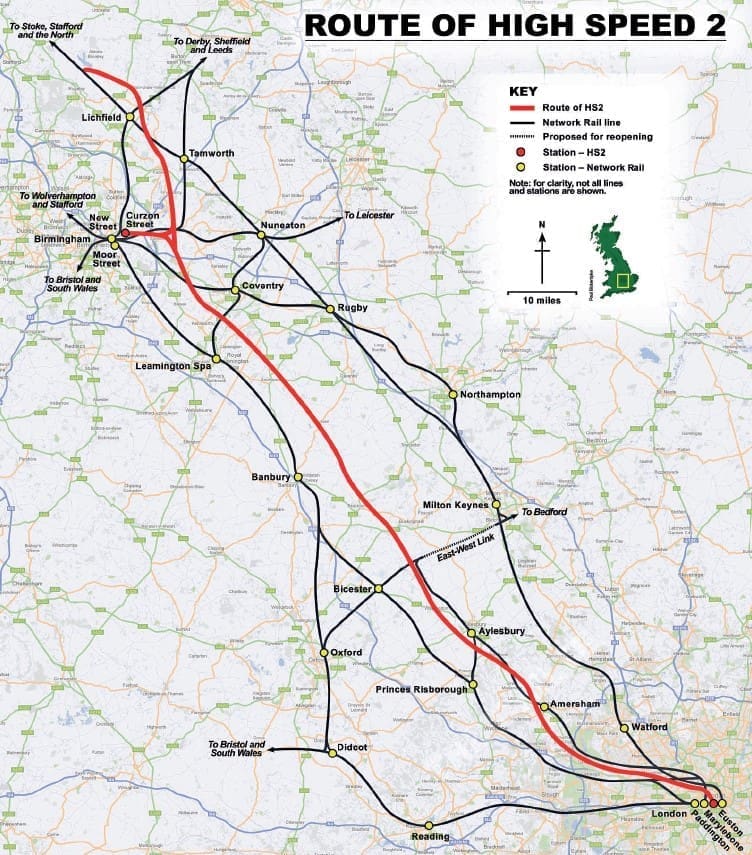

The line will be built in two phases. The first, between London and Birmingham is due to open by 2026 and the second, Y-shaped, part to Leeds and Manchester will follow by 2033. Revised details of the southern section route are shown on the map below.

A formal consultation on the second phase routes will begin in early 2014 with a final route chosen by the end of that year. The DfT has confirmed that the first phase of HS2 will include a connection to Europe via the Channel Tunnel, thus giving those living north of London the first probability of direct links with Europe since the plan for ‘Regional Eurostars’ was dropped in the mid-1990s. There will also be a direct link to Heathrow Airport, but it will be included as part of Phase 2.

Said Ms Greening: “A new high-speed rail network will provide Britain with the additional train seats, connections and speed to stay ahead of the congestion challenge and help create jobs, growth and prosperity for the entire country.

“HS2 will link some of our greatest cities – and high-speed trains will connect with our existing railway lines to provide seamless journeys to destinations far beyond it. This is a truly British network that will serve far more than the cities directly on the line.

“No amount of tinkering with our Victorian rail infrastructure will deliver this leap in capacity. It is not a decision that I have taken lightly or without great consideration of the impact on those who are affected by the route from London to Birmingham.

“I took more time to make this decision in order to find additional mitigation, which now means more than half the entire 140-mile line will be out of sight in tunnels or cuttings. I am certain this strikes the right balance between the reasonable concerns of people living on or near the line, who will be offered a generous compensation package, and the need to keep Britain moving.

“I could have made the easy choice; I could have gone for the short-term option, relying on a patch-and-mend approach and leaving our rail networks overstretched, overburdened and less resilient. But let us be clear; the price for that would have been paid in lost business, lower growth, fewer jobs and more misery for passengers on a network without the capacity to cope. We would have failed future generations depending on us to create the prosperous country they will want to live in.”

Contrary to the protests by those against HS2, the DfT and Network Rail says that there are no credible alternatives to a new line and that the £8bn WCML upgrade failed to deliver the promised 140mph line speed.

The DfT says that the £32.7bn highspeed line will deliver £6.2bn more of economic benefits than one running at conventional speed – and around £3.5bn more revenues – at a cost of only £3bn more than building a conventional speed equivalent. It says the line will benefit rail, road and air users and free up capacity on existing rail routes for more commuter, regional and freight services. It will take an estimated nine million journeys off the road network and cut up to four-and-a-half million air journeys each year.

HS2 trains will be up to 400 metres long with 1,100 seats, travelling at speeds of up to 250mph. Double-decker trains could be introduced to run on the HS2 network and would be compatible with HS1 and the Channel Tunnel.

Journey times on HS2 will be: London-Birmingham 45 mins (currently 1hr 24), London-Manchester 68 mins (2hr 08) and, when open, Birmingham to Leeds in 57 mins (2hrs).

Because of the strength of protests, Ms Greening agreed at a late stage to increase the number of tunnels along the route. A total of 22½ miles will now be in tunnel or cut-and-cover section compared with the 14½ miles originally proposed. A further 56½ miles will be in cuttings, meaning that less than half the line to Birmingham will be visible from the lineside.

The tunnel from Little Missenden to the M25 through the Chilterns is one of those being lengthened. It will now be a 2¾-mile bored tunnel along the Northolt corridor to avoid major works to the Chilterns Line and impacts on local communities in the Ruislip area.

There will be a longer ‘green tunnel’ past Chipping Warden and Aston Le Walls, and the route will be curved so as to avoid a cluster of important heritage sites around Edgcote. A longer green tunnel will reduce impacts around Wendover and there will be an extension to the green tunnel at South Heath. In HS terms, a ‘green tunnel’ is a subterranean concrete box with a rectangular cross section, covered in soil and landscaped.

The decision to go ahead with HS2 follows one of the largest public consultation exercises ever undertaken, with just under 55,000 responses received in five months. HS2 Ltd’s analysis estimates show that, over a 60-year-period, a national high-speed rail network would generate benefits with a net present value of up to £47.59 bn.

The net present cost to Government over the same period of building and operating the line would be £24-26bn.

On this basis, the Government’s assessment is that the proposed network would have a benefit:cost ratio of between 1.8 and 2.5.

The proposals still have to go through the formal planning process, and are expected to get a rough ride from those against the scheme.

Phase 2 (which includes a likely Heathrow airport spur and the northern extensions to Manchester, Leeds and possibly Scotland) will be considered separately over the next two years and a route map released at the end of 2014, following further consultations.

The Route

THE route of HS2 will run from a rebuilt Euston station to a new Birmingham city centre station at Curzon Street (the site of the former London & Birmingham Railway’s terminus, abandoned as a regular passenger station in 1854).

A Crossrail interchange station will be built at Old Oak Common in West London, providing direct connections to the West End, City and Docklands via Crossrail, and also to the South West and Wales via the Great Western Main line as well as to Heathrow via the Heathrow Express.

A second interchange station will be constructed where the line of route passes the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) and Birmingham Airport close to Junction 6 of the M42. It will offer direct links to Birmingham Airport, the NEC and the M6 and M42.

A direct link to HS1 will be provided in tunnel from Old Oak Common to the North London Line, from where existing infrastructure can be used to reach the HS1 line north of St Pancras. That will ultimately allow direct services between mainland Europe and provincial Britain.

Phase 2 will see the high-speed line running on to Manchester and separately to Leeds. HS2 Ltd is currently engaged in detailed planning work for options for these routes, including stations in East Midlands and South Yorkshire, as well as for a spur link to Heathrow.

Connections onto the existing West and East Coast main lines will also be included, allowing direct high-speed services to be run, initially, to Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Liverpool, Wigan, Preston, Lancaster, York, Durham and Darlington. Further consideration will be given to extending the network subsequently to other major destinations

Why the alternative proposals would not work

MANY opponents of the proposal, including the ‘Stop HS2’lobby and many local authorities, have been arguing on environmental and cost

grounds, suggesting that a better alternative would be a further upgrade of the West Coast Main Line.

The WCML upgrade that was completed in 2006 cost £9billion, took several years to complete, suffered numerous revisions and cost overruns, with passengers having to endure further horrendous delays, diversions and ‘bustutions’ during times of major work.

And all that pain didn’t even deliver all the promised gain. For a key part of the scheme was a planned 140mph line speed using ‘moving block’ signalling. That type of technology could not be developed for highspeed rail, which left a 125mph railway as a compromise. A whole two decades earlier, British Rail had had aspirations of 155mph with its erstwhile APT project.

To cater for soaring passenger numbers, operators have had to resort to longer trains (12-car Class 350 formations and Pendolinos have gone from eight- to nine-car and many will soon be 11-cars.This has meant changes to platform lengths, signal overlaps and all manner of infrastructure changes to allow high frequency services to many destinations.

Disruption

If yet another upgrade of the WCML was implemented, there would be many more years of passenger disruption, which would seriously damage business and the economy.

There are also infrastructure restrictions. It’s not possible to lengthen ‘Pendolinos’ to 12 cars, as proposed by the 51M group of local authorities, as (for example) given that the platform at Coventry sits between two road bridges and two junctions and cannot be extended without huge expense and disruption. It’s a similar situation at Wolverhampton.

Following the M40 would have made the line too twisty. Network Rail has said that alternative proposals fail to cater for projected increases in passenger numbers, which if HS2 was not built, would lead to intolerable levels of overcrowding (the Confederation of British Industry describes it as “gummed up”). HS2 would also free WCML paths for more local trains, and for the thousands of people that will move into the new homes planned for Buckinghamshire.

But it’s not just about cutting 45 minutes or so off the London- Birmingham time. There is a wider, emerging picture . If properly marketed, HS2 could eliminate the need for regional flights from London to provincial cities, cutting thousands of tons of CO2 at a stroke. It’s possible to still get a £59 London-Paris return, showing in Eurostar’s case the fares can win passengers from airlines – and with less minimal security checks too.

Britain is already lagging badly behind France, Germany, Spain, Japan and China in high-speed rail terms and there are many who feel that further procrastination will lead to a declining economy, with much more serious implications.