In the seventh of our series on the writers and artists who influenced the present generation of rail enthusiasts, Robert Humm recalls the life and times of the photographer, film maker, and pioneer preservationist Patrick Whitehouse.

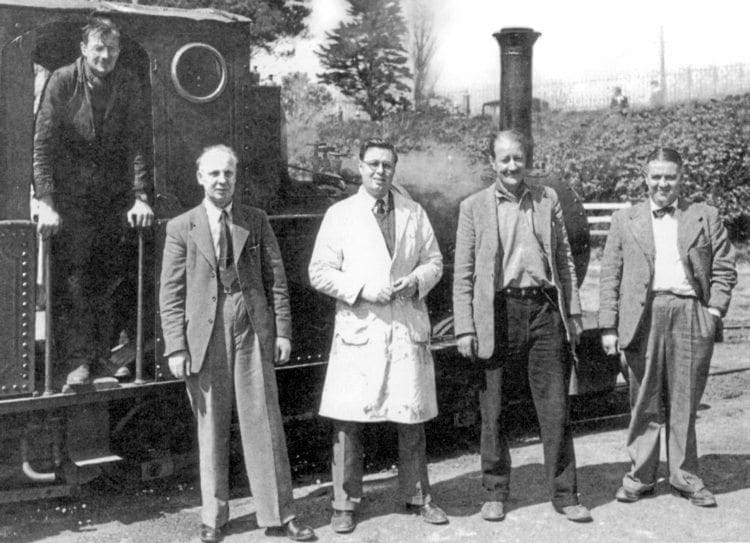

A phenomenon of the golden age of railway enthusiasm – those four decades of the 1950s to 1980s – Pat Whitehouse (left) was a supremely well-organised and persuasive ‘Mr Fixit’ with a string of achievements to his name. Preservation, books, broadcasting, photography, he contributed greatly to them all.

Patrick Bruce Whitehouse was born in Warwick on February 25, 1922.

In later life his photographs and notes were often initialled PBW and for brevity that is how I shall refer to him.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

His father, Cecil Whitehouse, owned a substantial construction company – B Whitehouse & Son – that was heavily involved in post-First World War renewal, new housing estates, blocks of apartments, and commercial and public buildings, mainly in the West Midlands.

His mother Phyllis, (née Bucknall), came from the Ellerman & Bucknall Lines shipping dynasty, a somewhat haughty family, who did not approve of their daughter marrying into ‘trade’ (shipowners were not trade, they were merchant princes).

In the 1920s and 30s Whitehouse family holidays were often spent in West Wales,

where the Welsh narrow gauge lines were on the doorstep for exploration.

It was undoubtedly there PBW developed his lifetime devotion to the narrow gauge picturesque that was to be the subject of so much of his early writing and photography.

In his early teens he owned a camera, and some of those photos, not at all bad, still survive.

After PBW completed his education at Warwick School it was intended he should join the family firm, but the outbreak of the Second World War put that on hold.

He volunteered for the RAF, where his wish to become a pilot was foiled by less than perfect eyesight. He did however qualify as a navigator, completing his training in Canada under the Empire Air Training Scheme.

Back in Britain he was posted to 15 Squadron and completed three tours of duty (each of 30 flights) in Lancaster bombers during the air campaign against Germany and occupied Europe.

That in itself was remarkable: the chance of survival was less than 10 per cent. For the rest of the war he served in the supposedly less arduous Transport Command in the Middle East.

There, he was shot down over the Mediterranean and was the sole survivor of the crew.

After four days adrift in an inflatable he was rescued by a Greek freighter.

By the time of demobilisation he had reached the rank of squadron leader.

Read more in the November issue of The RM – on sale now!