In the last part of our mini-series looking back to events of 50 years ago, Fraser Pithie considers a tragic accident that took place in early January 1968 on a section of the West Coast Main Line. It led to the first judicial and public inquiry into a railway accident since the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879. The consequences were to affect the progress of British Rail’s modernisation plans for several years afterwards, and proved to be a defining moment in level crossing use by motorists. Hixon was also a tragedy that could have been avoided.

Often it is said that a picture is worth a thousand words, and in terms of several or more railway accidents, many images have fulfilled this maxim.

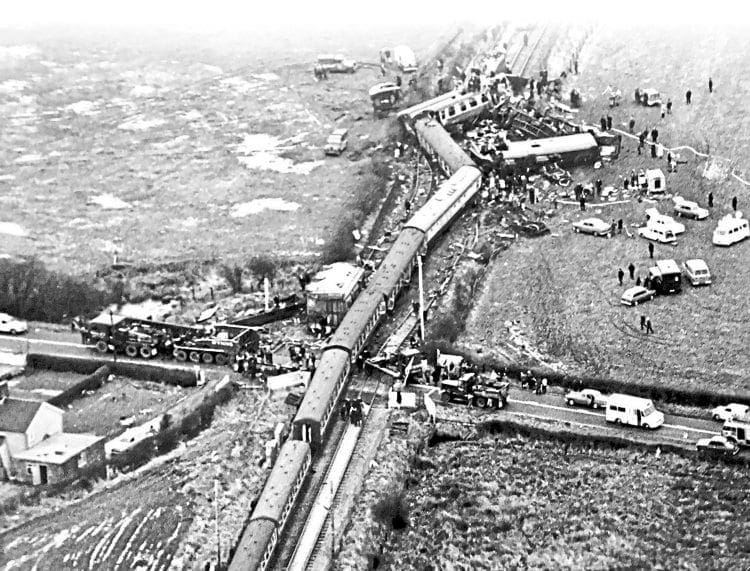

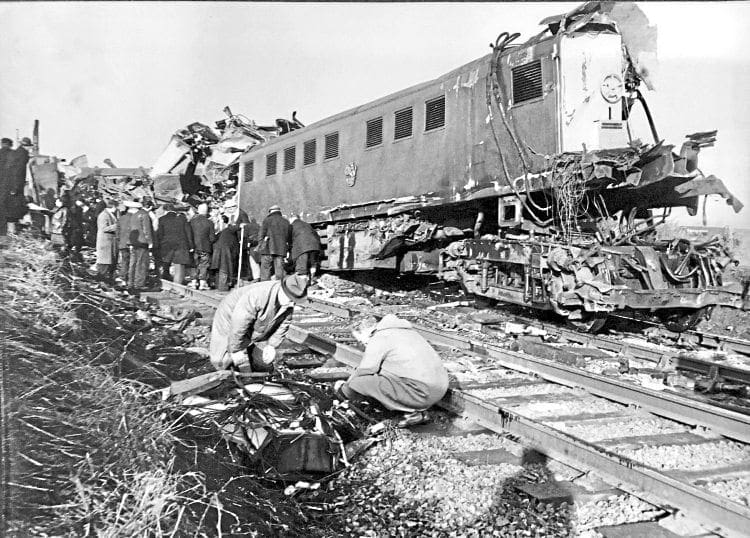

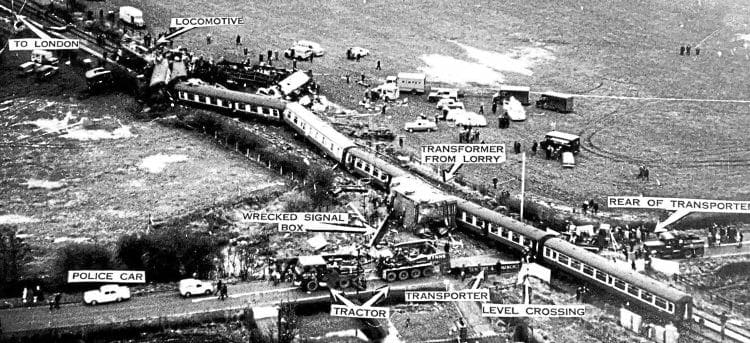

The dreadful events that took place near a disused airfield at a small hamlet known as Hixon in Staffordshire on Saturday, January 6, 1968 led to images that certainly conveyed the force and consequences of a high-speed rail/vehicle collision.

This was irresistible force meeting a nearly immovable object.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

As 1968 started, the modernisation of the railways, and in particular the West Coast Main Line (WCML), had advanced well.

Electrification between London Euston, Rugby, Birmingham and Wolverhampton, along with the Trent Valley section of the WCML from Rugby to Stafford, was complete to the main destinations such as Manchester and Liverpool.

Further electrification from Weaver Junction, where the line to Liverpool diverges from the WCML, north to Preston, Carlisle and Glasgow was to follow and be completed by 1974.

A regular and fast express electric train service using a new ‘InterCity’ brand was launched in April 1966.

It brought Manchester and Liverpool within three hours of London and was very much vaunted as the face of Britain’s ‘new modernised railway’.

The trains were hauled by new electric locomotives, taking their power from a 25KV AC overhead system.

With the initial electrification of southern sections of the WCML also came other modernisation elements, and this involved crossings with roads, right of ways and farm tracks/accesses. A number of options were followed from closing such crossings, upgrading them or automating them.

Background

To understand and appreciate some of the elements that were associated and likely contributed to what became a tragic event in 1968, one needs to go back more than 170 years to the early days of railways in the UK.

In 1845, Parliament determined that strict rules would be applied to level crossings with railways and highways, tracks, rights of way etc.

Initially, The Railway Clauses Consolidation Act 1845, (RCC), required that public level crossings be “manned and gated” with “good and sufficient” gates normally kept closed against the road, effectively fencing and securing the railway.

The RCC Act gave powers to the President of the Board of Trade to vary and reverse this practice, a power that was transferred to the Ministry of Transport in 1919.

Over the period from inception of the Act up to and beyond 1919, such powers were increasingly exercised where the volume of road traffic increased and exceeded the volume of rail traffic on a level crossing.

Most, and certainly major, level crossings required that the gates were interlocked with signals ensuring a train could only proceed after receiving a clear indication, which was only possible once the crossing gates had been closed against the road.

With the passage of time, the Ministry of Transport made judgments to vary more crossings.

However, this included some crossings, mostly that were not busy, to be changed without the protection of interlocking and signals.

In 1966 there were some 2,500 public level crossings with 514 gated crossings NOT protected by interlocking and signals.

Read more in January’s issue of The RM – on sale now!