The Nick Pigott Interview: For almost 40 years, artist Philip Hawkins has thrilled us with magnificent images of trains in all their glory. Now The Railway Magazine sketches the life story of one of the world’s greatest railway painters.

WHEN it comes to art, one man’s meat is another’s poison… and that’s especially true in the world of trains, where a widespread passion for rivet-counting realism makes railfans the most severe of critics.

Pleasing these armchair pundits is no simple task. A remarkably high percentage are perfectionists and wherever two or more are gathered together, a debate on railway art can be guaranteed to produce a lively and often heated exchange.

For many enthusiasts, the more esoteric aspects of painting, such as surrealism and post-impressionism, can safely be consigned to the realms of academia. Of far greater importance are such issues as the shade of the livery, the size of the tender logo and the shape of the driving wheels.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

If just one point has been badly executed – no matter how trivial the matter might appear to a non-enthusiast – the rest of the picture might as well not have been painted.

To be fair, some railway artists are their own worst enemies, portraying dreadful errors of perspective, wheels that don’t appear to run on rails, smoke that looks like cotton wool, coaches that bulge like balloons and numberplates that seem to fill half the smokebox. Engines depicted by such painters almost invariably have leaking cylinders, too. Why? Because the clouds of steam conveniently hide all that horrible complicated motion!

It was partly to weed out such amateurish efforts that the Guild of Railway Artists (GRA) was established in 1979 and one of its founder members was Birmingham-based Philip D Hawkins, who went on to become the guild’s chairman and president. As such, he is a person against whom such criticisms can hardly be levelled.

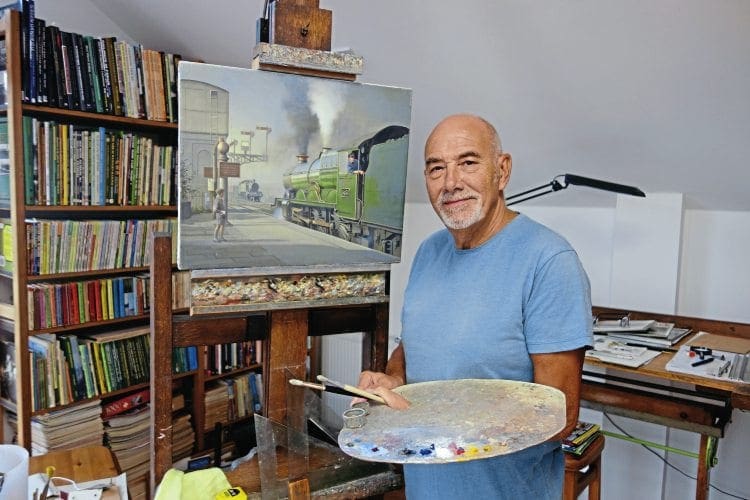

“In the early days there seemed to be a lot of poor pictures in circulation and the guild was formed to set a standard of which we could all be proud,” he told me as we relaxed in his studio overlooking the idyllic Devonian resort of Dawlish.

Phil and his wife Sonya moved to the West Country from their native West Midlands in 2001 to be close to the South Devon coast he remembered so vividly from boyhood summer holidays in the 1950s.

The famous sea-wall section of the Great Western Main Line was a big influence in their decision too, for Phil never tires of portraying Swindon-built masterpieces.

The word masterpiece is one that has been applied many times to his own works of art, which today sell for thousands of pounds. Each one takes an average of between six and 12 weeks to paint depending on size, complexity and time required for preliminary research, and he has now produced some 200 since turning professional in 1978. At the moment, his waiting list stretches well into 2018.

The man who has become one of the world’s greatest transport artists was born a stone’s throw from the GWR’s Tyseley roundhouses in September 1947 and grew up in a terraced house backing onto the embankment of the ex-LNWR Soho loop line in the Birmingham district of Winson Green.

“It was a free show for me every day,” he recalled with a big smile. “Ex-LMS ‘Jubilees’, ‘Royal Scots’, ‘Patriots’ and ‘Black Fives’ used to parade past the windows… while a short walk away at the end of the street was the former GW main line from Snow Hill to Wolverhampton with ‘Kings’, ‘Castles’, ‘Counties’, ‘Halls’ and ‘Granges’. In the middle was a patch of land between two bridges from where it was possible to see the numbers of engines on both lines.”

Engine driver

That alone would have encouraged most lads to become spotters in those heady days, but the young Hawkins had an additional strong reason to be interested… for trains are in his DNA; his great-grandfather had been an engine driver and had spent a 50-year career working for the LNWR and LMS between 1880 and 1930.

“He’d been based mainly at Monument Lane shed and when I was about 11, my dad had the brilliant idea of taking me there to show me where he’d worked. Witnessing the engines from ground level was a magical and awe-inspiring experience and I was even allowed to cab my favourite ‘4F’, No. 44444. Engines of that type we knew as ‘Duck 6s’ and other nicknames we had were ‘Duck 8s’ (for ‘Super Ds’), ‘Blackies’ for Stanier ‘5MTs’ and ‘Consuls’ for Stanier ‘8Fs’.

“It was while going round Monument Lane that it dawned on me that the engines I saw every day on the embankment didn’t all come from local sheds but could be based in far-off towns and cities, some even as far away as Wales or Scotland. From then on, I was really hooked!

“A couple of pals and I therefore decided to see if we could visit other depots, so we caught a train from our local station – Handsworth & Smethwick – to Wolverhampton Low Level and then another to Dunstall Park, where we’d been told you could get into the yard of Wolverhampton Stafford Road shed by nipping off the platform. After getting as many numbers as we could there, we walked along the canal towpath to Oxley depot, which was mainly a freight loco shed. Over the next few weeks, Tyseley, Saltley and Aston MPDs were added to the list.”

So far so good, but those were all local sheds and the boys’ appetites for more distant meccas had been whetted, so at weekends, they would tell their mums they were going round to each other’s houses to ‘play’… then jump on a train and travel miles to somewhere like Crewe or Chester for the day! To help their pocket money go as far as possible, they did what a lot of likely lads did in those days and used various money-saving ploys involving platform tickets and suchlike. They also learnt over time which were ‘open’ stations and which trains were most likely to have ticket inspectors. Saturday football specials helped a lot too as they were good for really low fares to such places as Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Sheffield.

“If our parents had known what we were up to, they would have gone raving mad,” said Phil, “but my mother was a real brick and had helped me a lot with my hobby during my time at Boulton Road Junior School. She knew I could see trains from the playground but that they were too far away to get the numbers, so she’d make a note of any ‘namers’ she saw passing her kitchen window during playtime and when I got home I could see what I’d missed. One day she handed me a list with ‘Patriot’ No. 45528 on it. I said ‘No, mum, that’s not a namer’, but she swore blind it was.

Procession

“It wasn’t until later that I found it had been named REME a day or two before. Such changes didn’t appear in the railway press in those days until weeks, sometimes months, afterwards.”

Another place that was frustratingly too far from the line was Exmouth, in Devon, to where Mr and Mrs Hawkins took Philip and his sister on a summer holiday in 1960. Recalls Phil: “Where we were staying was on a branch line and it was infuriating to see the procession of main line trains passing Starcross on the other side of the wide River Exe more than a mile away, some of which I could tell were hauled by brand new ‘Warship’ diesels. Fortunately, I’d taken the precaution of writing off in advance for permits to visit Plymouth Laira and Exmouth Junction depots, although we only got to the first of those as dad said he couldn’t find the Exmouth one on a map!

“The previous year’s holiday – a fortnight at Dawlish Warren – had been far more productive, including the excitement of seeing my first-ever engine with a number beginning with ‘3’ while changing trains at Exeter St David’s. It was ‘Battle of Britain’ Pacific No. 34079 141 Squadron.”

At the age of 13, in 1960, Phil was able to afford an Ian Allan Combined Volume for the first time and also joined the Birmingham Locospotters Club, triggering three glorious years in which he travelled the length and breadth of the country by road coach on shed-bashing tours. In addition, he and a group of friends organised a number of private trips, often involving a midnight departure from New Street to places such as Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester or Carlisle, returning home just in time to grab a few hours sleep before school on Monday.

Such experiences will ring a bell with many readers and gave the lads plenty of bragging rights over less adventurous spotting mates at school on Monday mornings.

Clandestine

An advantage of the organised tours, compared with the clandestine days-out Phil made when he was younger, was that his parents knew about them. This was very useful when the returning train services didn’t work out as planned or the money ran out before they’d got home, because it meant that Phil could ring home and ask his father if he’d collect them in his car. “I remember there was at least one late-night rescue mission from Rugby and another from Crewe. As dad was in the licensed trade, he had to work in his off-licence shop until 10pm, yet he could always be relied upon in an emergency.”

Like many boys, Philip loved drawing and the trains that passed his house every day when he was a youngster made ideal subjects. “I was always asking for drawing books when I was a little kid and I had a small paintbox with ‘cakes’ of water-colours that could be replaced when they ran out. That’s how I learnt about mixing colours.”

In the classroom, Philip found he could paint much better than the other children and it was thus a natural progression to go to Birmingham College of Art & Design upon leaving school. His parents weren’t keen, taking the view that art wasn’t a ‘proper job’, but Phil smiles at the irony of those comments now as the demands of his commissions frequently keep him at work from eight in the morning until gone midnight. Fortunately, wife Sonya is also a professional artist (although not of railways) and fully understands the situation.

Given his background, one might have expected Phil to find early fame as an oil painter, but it was as a technical illustrator at Birmingham’s Metro-Cammell carriage & wagon works in Washwood Heath that he made his living after graduating in the late-1960s.

Part of his role there involved creating artist’s impressions from company blueprints to show clients before construction, but although the work was rail-related, he found his interest waning as a result of the end of BR steam a short time previously and decided to make a living from his other great passion – photography. He thus became a freelance press photographer, working for the Birmingham Post, Sunday Mercury and other West Midlands papers before joining the Solihull News as a staff photographer in 1970.

The varied world of local journalism saw him covering anything from fetes and fashion to sport and even Father Christmas arriving in a helicopter, and it wasn’t until the summer of 1972 that the railway interest began to return.

Good partnership

Phil explained: “I was on holiday in Cornwall with the family and saw a train hauled by a ‘Warship’ diesel-hydraulic. I’d lost touch to such an extent that I thought they’d all been withdrawn so I spent much of the rest of the holiday on the lineside with my camera rather than on the beach!”

Once the bug had bitten a second time, Phil gradually became more and more active on the rail photography side and contributed photos to railway periodicals while keeping his hand in with his art hobby whenever he could. He was thus almost 30 years old before his first railway painting was published (a portrait of a ‘Britannia’ in Locomotives Illustrated) and finally, in 1978, he decided to take the plunge and become a full-time railway artist.

Since then he’s gone from one extreme to the other, managing to get almost every one of his paintings published in one form or another, either in books and magazines or as calendars, greetings cards and limited-edition fine art prints. In this regard, he has benefited greatly from the marketing skills of his agent, Bernard Apps, of Quicksilver Publishing, with whom he joined forces in 1988.

Bernie and Phil had attended the same schools in Birmingham and decided to go into business together after the BBC commissioned a canvas of the ‘Cornish Riviera Express’ for its Children in Need charity programme. The prints sold very well and on the back of that success, the men decided to launch Quicksilver, although Phil reveals that he had at first wanted to call the company Time Machine.

“It’s been a good partnership and my advice to anyone considering taking up railway art is to team up with someone who has a head for figures,” says Phil… “because artistic temperament and sound business sense don’t normally go together!”

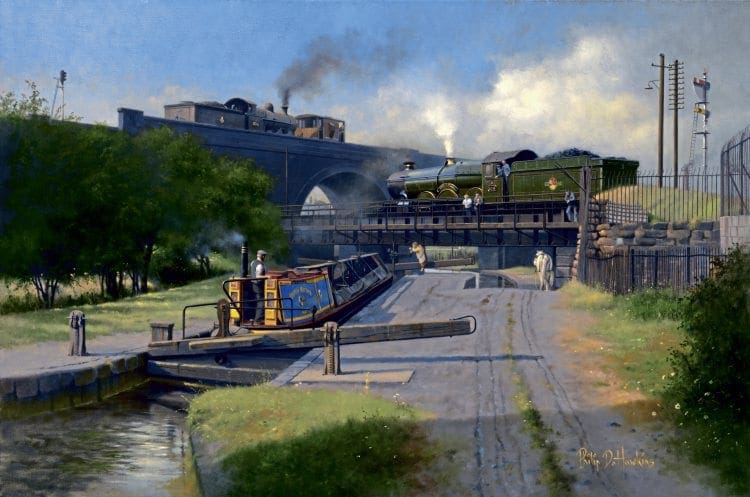

Work-stained

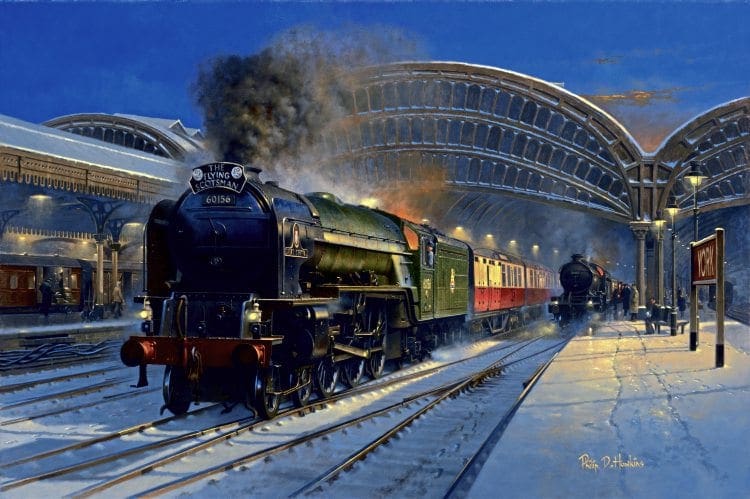

The original oils on canvas from which the prints are made are, of course, sold to whoever commissions them and owning one is now a symbol of status in the world of railways, putting the Dawlish-based painter in the fortunate position of being able to choose which projects he accepts. “The first stage is to have a long chat with the client and if what is required is an image of a preserved locomotive, I usually try to find a way of declining the job,” he admits. “I just don’t feel at home painting spotlessly clean, brightly coloured engines. I love visiting preserved lines such as the Severn Valley and West Somerset, but I grew up in an era when BR steam locos were grimy and work-stained and that’s what I prefer re-creating.”

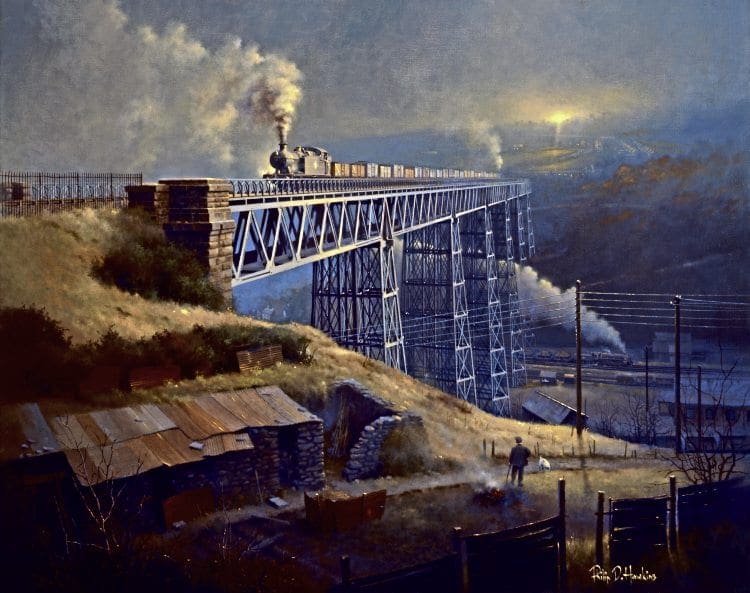

Phil does, however, enjoy the challenge of working on Big Four and pre-Grouping scenes, especially as a painting is often the only way they can be illustrated in colour, and he is equally adept at transforming what some would consider relatively lifeless diesel and electric subjects into atmospheric images.

The latter skill has brought him major commissions over the years from companies such as Eurostar, Freightliner, Virgin Trains and Docklands Light Railway. “Working for corporate clients like those has benefits over and above the fee,” he says. “You get first-hand access to traction depots and other places you’d normally only be allowed to view from outside the fence and there’s usually the bonus of a cab ride, too.”

Overseas subjects are not something Phil is widely known for, but he recently accepted a commission from a Yorkshireman who lives in the German city of Hamburg and wanted a painting of the Mollibahn, a narrow gauge steam line that runs through the streets of Bad Doberan. “I quite enjoyed that. I spent a few days out there, riding the line with him and getting an understanding of what it was he wanted.”

This insistence on visiting a site in advance is one of the Hawkins hallmarks. Even when asked to produce a scene he knows well, his professionalism won’t allow him to put brush to canvas until he has personally explored the site. Not for him the easy option of copying from a photograph in a book… he has to get a ‘feel’ for the area and will always make a rough sketch showing angles, perspectives and the

all-important fall of shadows at various times of the day. Even if the line, station or depot has long-since vanished, he will still visit in the hope of finding a surviving building or distinctive horizon that will help set the scene into context.

An exception to the use of photos comes when he needs to paint a steam loco type that is no longer in existence. Where an example does survive, he will visit the relative museum or heritage line and take its measurements, but when the class is extinct, he relies on statistics and pictures, although he points out that many of the photos he uses he took himself during the 1960s.

Clients vary

Unlike many of his spotter contemporaries, Phil had owned a camera and made sure he popped it into his duffle bag on shed-bashing trips. His first in 1960 was only good for static locos, but from 1963 until 1966 he had a Voigtlander Vitoret and after that a Pentax with interchangeable lenses. The pictures he took in those days have since become valuable sources of reference when researching paintings. He’s also managed to retain most of his many notebooks and those too come in handy when needing to know which locos to paint into a particular location.

“Clients vary in the way they commission me,” reveals the artist. “Some present me with the most highly detailed specifications involving several meetings and copious piles of notes, while others are content with a single vague request.

“I normally work up some pencil sketches from different viewpoints to discuss with them and I ask for a 25% deposit as an act of good faith following a few early experiences in which I spent hours and hours on research only for prospective clients to cancel or change their order.

“Once the details have been agreed and the deposit paid, though, I like to be left alone to execute the painting. If the client doesn’t like it when I’ve finished, he doesn’t have to pay the balance and accept it, but so far, touch wood, I’ve not had one rejected, which cannot be said of all artists.”

Criticism of other people’s work might seem a little uncharitable, but it’s an essential part of Phil’s work for the Guild of Railway Artists.

Prospective entrants are required to present a portfolio of their work to a selection committee on which Phil has often sat, but he concedes that the paintings of which he is most critical are his own! “I often look back and think I could have done better.”

Problems in the early years included an inability to know when to finish work on a canvas and a failure to ‘loosen up’, resulting in paintings that felt ‘taut’. He has a reputation for technical accuracy (something reinforced while at Met-Cam) and would sometimes spend weeks and weeks on a single painting, constantly touching it up. “Some days I would even take out more paint than I put in! No wonder I sometimes fell behind schedule, but I gradually learned that such fiddling doesn’t necessarily make for a better product.”

A good case in point is his famous rendition of two garter blue ‘A4s’ passing at Grantham in LNER days, which took him just eight days from start to finish. “That was one of my best paintings and since then I’ve been better at knowing when to stop. If I do start to slip back into old habits, Sonya has developed an effective line in backside-kicking and honest, incisive criticism when apathy or despair threaten to take over. I also find it helps to have the threat of a deadline or the fear of letting a customer down. Daylight-replicating lights in the studio enable me to work late into the night if necessary.”

The GRA was founded in 1979 by Frank Hodges, who ran it as chief executive until recently and who, says Phil, “deserves a medal for everything he’s done for us all. We’ve been able to meet kindred spirits, share problems and solutions and give each other encouragement whenever necessary.”

Honour

Phil was elected chairman of the guild in 1988 and became president when the title was changed a couple of years later. He remained at the helm until 1998 when the accolade of Honorary Fellow was bestowed upon him by members, making him only the third artist to receive such an honour after David Shepherd CBE and the late Terence Cuneo OBE. In the 18 years since then, only two others have been similarly elevated – Malcolm Root and John Austin.

Cuneo in his prime was an inspiration to many of today’s railway artists, but Philip also admires the work of one of the most celebrated English painters of all time – J M W Turner.

For years, a small print depicting one of Turner’s Venetian masterpieces shared company with locomotive subjects on the wall of the Hawkins studio – a constant reminder that railway art can count among its exponents one of the greatest masters who ever lived. For Turner’s Rail, Steam and Speed, a brilliantly impressionistic rendering of the then-new GWR in 1843, helped initiate a genre whose popularity has mushroomed since the demise of BR steam began, driving more and more rail enthusiasts to seek mementos of their lost youth.

Ironically, Phil’s order book is now so full that he rarely has time to produce a painting for himself and if he does, it’s usually a small one he can finish in a reasonably short time. Such a work was on his easel the day I visited in August – a 20in x 16in canvas of ‘Castle’ No. 5037 Monmouth Castle he was producing for the guild’s Railart 2016 exhibition at Kidderminster Railway Museum. Entitled Waiting at Oxford, it’s a minnow compared with the enormous 54in x 36in portrait of Birmingham Snow Hill he once produced for a firm whose offices overlooked the station site. Another Snow Hill scene – depicting crowds of holidaymakers heading for the seaside on a summer Saturday – became one of his best-selling works after being promoted by the Birmingham Post & Mail newspaper group. Eager Brummies snapped up more than 5,000 prints.

Noticing that the Monmouth Castle painting included a schoolboy spotter complete with one sock up and the other down in the affectionate ‘Just William’ style of the era, I couldn’t help asking Phil if it was a self-portrait. His reply was disarmingly honest: “I think, subconsciously, that all the trainspotting kids in my paintings are me… a psychiatrist would have a ball!”

Phil’s children, Nina and Ben (now grown-up), also appeared in some of his early works, and although they don’t share their dad’s deep interest in trains, Ben has inherited a skill for photo-journalism and is currently editor-in-chief of photography titles at a firm of national magazine publishers.

The shed visits of Phil’s teenage years – he managed to get to most of the main ones in England, Scotland and Wales before he was 20 – have left him with an indelible feel for those ‘cathedrals of steam’ and the impressions of hot oil, coal and ash that played on his senses have given him an innate ability to paint it ‘just as it was’.

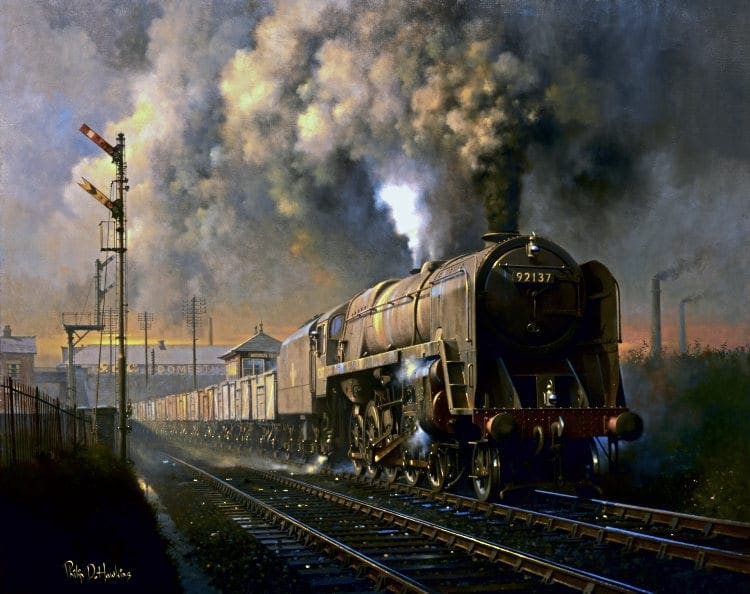

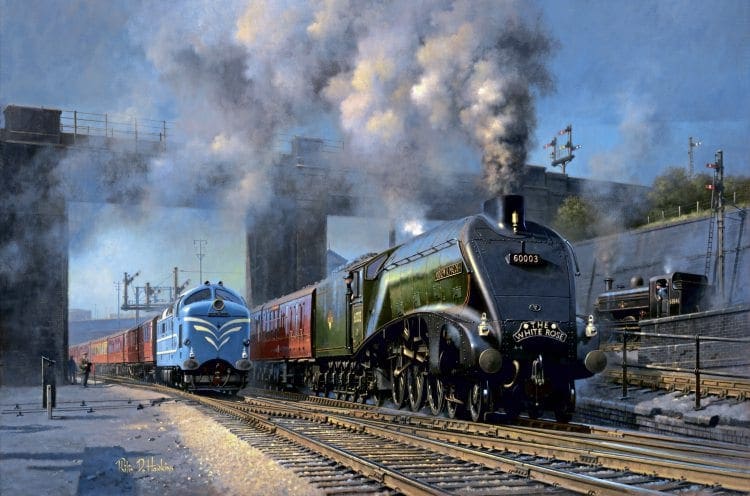

‘Night Wolf’ (which appeared on the front cover of our October 1992 issue) and ‘Unsung Hero’, depicting a careworn Robinson ‘O4’ class 2-8-0, are just two paintings that convey the atmosphere and clutter of BR steam sheds to a T. Three more of Phil’s paintings have graced the front covers of The RM – ‘Night Freight’ in October 1994, ‘North Pole Dawn’ in March 1995, and this year’s September cover featuring Thornbury Castle.

These and many other examples of his work have been published in two large format volumes – Tracks on Canvas and Steam on Canvas – both from the stable of the excellent OPC publishing company and each containing some 50 works of art bearing such clever titles as ‘Summit Meeting’ (two trains passing at the top of the Lickey incline) and ‘Evening Standard’ (a night shot of No. 73156). I can recall perusing both books for errors of detail or perspective and, somewhat perversely, feeling a little cheated when I couldn’t find any worth mentioning!

One of the reasons for this is that Phil is meticulous in both research and execution and his uncanny ability to combine the all-important ‘look’ of an oil painting with the accuracy of a photograph is one of the reasons why he has been at the top of his profession for so long.

“People might wonder why things like my childhood holidays and days-out are so important to my work,” he comments. “It’s because all the books and photos in the world can’t beat the fact of ‘being there’; the unmistakable aroma of steam, the thrill of seeing a rare locomotive, of walking around sheds surrounded by the sights, sounds and smells of everyday working steam – but most of all, the excitement and anticipation of setting out on those adventures.

“Such recollections fuel my imagination all these years later and prevent me from staring at a blank canvas, not knowing how or where to start.

“I consider myself fortunate to have such wonderful memories… and fellow rail enthusiasts will know exactly what I mean.” ■

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 120 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.