For more than 150 years, the three Thames Valley branch lines have been vital commuter and leisure routes serving Windsor, Marlow, Bourne End and Henley-on-Thames. Facing modernisation, Stuart Warr looks at the fascinating history of these branches and what the future holds.

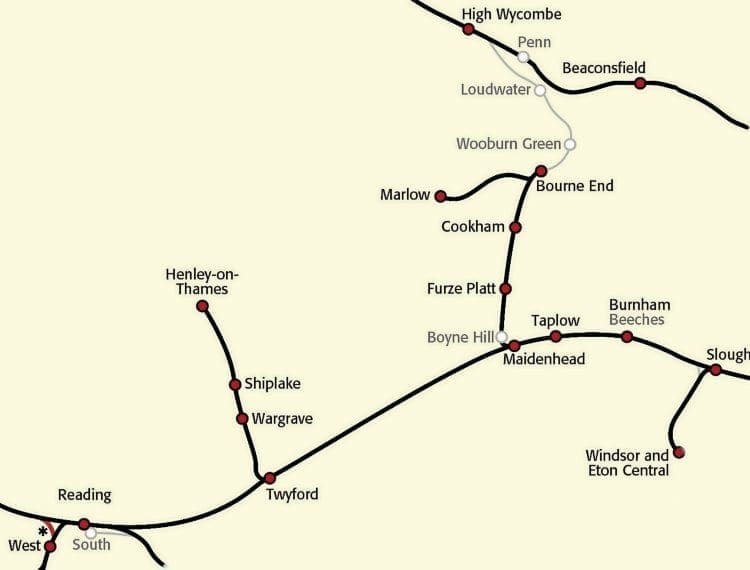

THE Thames Valley branch lines to Henley-on-Thames, Bourne End, Marlow and Windsor are connected to the Great Western main-line at Twyford, Maidenhead and Slough, respectively; to many passengers the junctions are glimpsed as their High Speed Train (HST) races past en route to or from London Paddington, but for those who use the branches they are a lifeline for both commuting and leisure travel, often being speedier than travelling by road.

With the advent of modernisation just around the corner, it is an appropriate time to review the three branches in some detail.

The termini of the three branches are each in different counties: Oxfordshire (Henley-on-Thames), Buckinghamshire (Marlow) and Royal Berkshire (Windsor) with a tri-point where all three counties meet; one of a number of common denominators is that they are all situated on or very near the River Thames.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Henley-on-Thames branch

The (original) Great Western Railway reached Twyford in 1839, but it was eight years later that an Act was passed to give the power to construct the branch; financial constraints delayed the start of work so much that in 1852, motivated by the risk of incursions into its perceived territory by other railway companies, the GWR sought an extension of time to complete the work.

Topographically, the branch has no major challenges, the steepest gradient being 1-in-64 for a couple of hundred yards into Twyford and at four miles and 49 chains in length, the branch opened in June 1857 as a single line built to the broad gauge with an intermediate station at Shiplake; the line was changed to standard gauge (in GWR parlance known as narrow-gauge) in March 1876, the work being completed overnight with just two train services cancelled.

The suffix ‘-on-Thames’ was added in 1895 so as not to cause confusion with Henley-in-Arden, a small town in Warwickshire, where a station was opened in 1894.

Passenger traffic had more than one flow, commuters out in the morning, returning later in the day and holiday/leisure usage, especially in connection with the Henley Royal Regatta, held annually in early July. Usage was such that between 1896 and 1898 the branch was doubled and two years later a new station was added at Wargrave. Also in the years immediately before and following the start of the 20th century platforms and canopies at Henley were lengthened and additional sidings provided.

During much of the last century about 20 daily passenger services operated in each direction, some ran to/from Paddington and others to/from Reading, but most worked only on the branch. For example, the summer 1959 timetable showed 25 weekday services in each direction with two morning peak trains going ‘up’ to Paddington, with a corresponding number returning in the evening peak. By comparison the equivalent timetable in 2016 had 29 services on the branch, with two morning peak workings to Paddington and three in the evening from the capital; one service worked to and from Reading, but appears to be primarily for operating rather than commercial reasons.

As with many branch-lines from the late 1950s usage retracted in both freight and passenger services as a result of the levels of private car ownership and the movement of goods by road. By 1961 this retraction allowed British Railways to single the branch, retaining a passing loop only at Shiplake, which closed in 1968. Henley’s goods yard closed in 1964 and by 1969 its three passenger platforms were reduced by one.

The 1970s brought further contraction, with the station buildings at Henley being demolished in 1975, but 10 years later a joint development with a local company led to the shortening of the branch by about 200 feet and the construction of a smart new station building appropriate to area. Though the branch was shortened, some of the platform canopy remained, as it does to this day; some of the land released by the shortening was utilised to build offices for the company with whom the development was jointly agreed.

In 1985 the buildings were demolished at both intermediate stations with waiting facilities provided by ‘bus-style’ shelters. Shiplake appears to be quite verdant, but is an adopted station and is cared-for to a high standard befitting the beautiful village in which it is located. The following year saw one of Henley’s two platforms demolished, allowing further car parking. This meant that the branch from Twyford was now a four-and-a-half-mile-long siding.

At the time of the opening of the branch a small engine shed (sub-shed of Reading, 81D) was constructed at Henley-on-Thames and primarily used to house the locomotive that worked on the branch; dieselisation came quite early to this area and the shed closed in 1958 when the majority of local services were operated by first-generation DMUs. However, steam to and from the capital lasted until June 1963 when both inter-city DMUs and diesel locomotive-hauled sets were used, more of which later.

The branch is particularly heavily used during the various regattas held in Henley, the most famous one being the Henley Royal Regatta, held each July. It is probably the best known regatta throughout the world, attracting as it does, elite rowers to take part in races on the Thames, and attracts thousands of visitors, some of whom travel by train.

The Privatisation of the railways has brought both good and not so good aspects to the UK rail system. One of the good points has been the identification of some lines around which marketing strategies have been formed, logos designed and shown wherever possible (on timetables, station signage, etc) leading to a form of local ownership and a level of pride for both users and staff.

In 2005 the franchisee holder, First Great Western (FGW), and Oxfordshire County Council agreed to the Henley branch being marketed as the Regatta Line; its logo is four rowing oars and a stylised image of Henley Bridge. In terms of colour, blue signifies the river and purple is one of FGW’s corporate colours.

Having looked briefly at the history and infrastructure of the branch, turning attention to motive power and other interesting points, steam haulage has predominantly been in the hands of tank engines as would be expected on such a line.

On June 1, 1857 the first train was hauled by a ‘Leo’ class 2-4-0T named Virgo. Since the Nationalisation of the railways after the Second World War local services were operated by GWR-designed Pannier tank locomotives. Heavier services and those to Paddington, for example, would have had tender engines such as the ‘Hall’ class 4-6-0s, these being the biggest engines able to use the turntable at Henley.

Dieselisation arrived early to the branch, with some indications that in 1934 one of the GWR’s AEC-built railcars operated some trips, but during the 1950s others worked on the branch.

As mentioned earlier, local services were dieselised in 1958 when first-generation DMUs started work on the branch. Classes used included 103, 117,119 and 121, which lasted until being replaced by Class 165s and 166s in 1992/93.

Following the final steam-hauled services to Paddington in 1963 diesel-hydraulics became the main motive power, but Class 123 Inter-City units worked some services. Anecdotally, commuters complained bitterly about the use of such units on the Paddington trains and the

Class 123 DMUs were replaced by the locomotive-hauled stock, at least in the short term.

The branch was marketed in the 1930s and mid-1950s to the early 1960s as a holiday destination. Camping coaches were located at Wargrave between 1936 and 1939 and from 1953 to 1964. Shiplake was also graced with a camping coach between 1956 and 1963.

The GWR-invented Automatic Train Control system was successfully trialled on the branch before being rolled-out to the rest of the GWR network.

One member of rail staff has been formally acknowledged. Norman Topsom joined BR (WR) in 1962 at Henley-on-Thames as one of 40 on the station payroll. He retired in 2015 following 20-years at Twyford as chargeman, and for services to the rail industry he was awarded the MBE. Known to all his local customers as ‘Mr Twyford’, and immediately recognisable because of his bushy white whiskers, he was honoured further by GWR, who named a

Turbo-Unit (166204) after him.

Bourne End and Marlow branches

The line from Maidenhead to Marlow is really the remaining sections of two lines, now largely regarded as one branch. Maidenhead was joined to London Paddington by rail in 1838, though neither of the stations were in their current positions, but it was to be some years before a line was constructed towards either Bourne End or Marlow.

The Wycombe Railway was the subject of a Bill in Parliament to construct a line from Maidenhead to High Wycombe in 1846, but in 1852 an Act authorised the building work, with the line being leased to the GWR.

By 1854, a broad-gauge single line almost 10 miles long was opened with stations at Maidenhead (Wycombe branch) which, in the 1860s was renamed Maidenhead Boyne Hill and located near (but not at the junction) Cookham, Marlow Road, Wooburn Green, Loudwater and High Wycombe. Thirteen years later the Wycombe Railway was absorbed by the GWR and the line converted to standard gauge in 1870.

Two years earlier the Great Marlow Railway was authorised to build a branch from Marlow Road (renamed Bourne End from 1874) to Great Marlow (renamed Marlow from 1899) which opened in 1873; it was constructed as a standard gauge line. In 1871 the current Maidenhead station opened, bringing about the closure of the original station in the town; services bound for the High Wycombe line used a platform face on the Up passing loop; a short train shed at this platform helped protect passengers from inclement weather.

A passing loop and platform were constructed at Cookham in 1904 and Loudwater station just a passing loop was provided, also in 1904; of interest at Cookham was the use of Chiltern chalk with red brick quoins as materials to construct the station buildings, an attractive alternative to the more usual engineering bricks or stone. Not now in railway use the buildings on the former Down platform are still extant and in commercial use.

Bourne End was built with a passing loop and second platform for the services between High Wycombe and Maidenhead; a third platform and run-round loop was provided on the northern side of the ‘mainline’ for the branch services for Marlow. The branch to Marlow from here has no intermediate stations and is two miles and 52 chains in length, also from Bourne End the line to Maidenhead is 4 miles and 36 chains long. When built, Marlow benefited from a small engine shed (sub-shed to Slough, 81B); goods facilities were provided here and at Cookham, Wooburn Green and Bourne End.

The requirement for a line from Maidenhead to High Wycombe diminished in 1906 when a line was opened from the latter town to Northolt Junction, built jointly by the Great Western & Great Central, providing direct lines to London’s Paddington and Marylebone stations; the line became a bit of a backwater after this.

However, in 1937, Furze Platt Halt was opened to serve the eponymous village and the developing residential area of North Town.

Later in the 20th century further decline occurred. The run-round loop at Bourne End was taken out of use in 1955, and goods facilities were withdrawn from Maidenhead and Cookham in 1965, Marlow in 1966 and Bourne End in 1967; the engine shed at Marlow closed in 1962.

Following the withdrawal of goods facilities at Marlow the yard and station were sold and a new platform built on the south side of the site, which opened in 1967. Passing loops between Maidenhead and High Wycombe were removed in 1969; at Bourne End the platform previously used for northbound trains was, after this date, used for the Marlow services, allowing further track rationalisation here. Cookham’s footbridge saw further use at Pewsey following singling, and the line north of Bourne End to High Wycombe closed completely in 1970.

Having reviewed briefly the physical history of this route, let us look at its workings. The comparison between an old timetable and that of a current one is not strictly on a level playing field as a result of the closure north of Bourne End, but it makes interesting reading.

Using the summer 1959 timetable, weekday services on the branch included two direct to Paddington, one each from High Wycombe and Bourne End, both in the morning peak; 11 from High Wycombe (one extended to Slough in the morning peak); and three from Marlow as far as Maidenhead, with 21 from Marlow to Bourne End. Connections at Bourne End for Maidenhead were poor, with a number of long waits in excess of an hour, though connections to High Wycombe appear shorter.

In the reverse direction, six through trains from Paddington – one in the morning peak, three in the equivalent evening peak and two during the later evening; from Maidenhead to High Wycombe seven services were operated, including three starting at Slough. Finally, 21 services from Bourne End to Marlow, with three starting from Maidenhead.

Looking at the timetable, the potential traveller could not rely on anything like a

‘clock-face’ service and would need to check and double-check times before setting out.

The equivalent timetable for weekday services during the summer of 2016 shows 11 trains from Marlow to Bourne End, an additional 11 continuing to Maidenhead, and 14 from Bourne End to Maidenhead, with two continuing to Paddington during the morning peak.

Returning, 12 trains operate from Maidenhead to Bourne End, with three emanating from Paddington and 24 from Bourne End to Marlow, including 13 from Maidenhead. This timetable is clearer with more user-friendly services and an element of ‘clock-face’ departures, a big improvement for the potential traveller.

Post-nationalisation steam services were worked by a variety of ex-GWR tank engines, with Prairies and Panniers working many of the trains between Maidenhead and High Wycombe; ‘14XX’ Class 0-4-2Ts worked the shuttles between Bourne End and Marlow. Dieselisation arrived in 1962, with first-generation DMUs working on the branch, predominantly of Classes 117 and 121; these lasted until 1992/1993 when the Class 165s and 166s replaced the earlier designs and provided a better journey experience.

Two points of interest to conclude the review of this branch: firstly, the branch is affectionately known as ‘The Marlow Donkey’ or just ‘The Donkey’. This name originally applied to the Bourne End to Marlow section, but now that the branch is defined as starting from Maidenhead this nickname is applied to the whole line.

What of its derivation? There is no definitive answer, but the most likely sources are either the name given by locals referring to the ‘trains of pack horses, mules and donkeys carrying goods to the riverside’ that pre-dated the railway; or, a pub in Marlow is named The Marlow Donkey (allegedly after the unofficial name of the locomotive that first worked on the branch in 1873, numbered 522 – a member of the ‘517’ class).

The GWR did not promote these two lines as potential holiday destinations as much as they did the Henley-on-Thames branch, but for the summer of 1960 only a camping coach was at Bourne End.

Windsor branch

Earlier it was noted that 1838 saw the opening of the railway from Paddington to Maidenhead, but Slough’s station did not open until 1840, owing to pressures from Eton College.

A broad-gauge branch line from Slough was opened into Windsor in 1849, it being the first railway station in the town, opening less than two months before the one that was to become known as Windsor & Eton Riverside.

The branch was short at two miles and 63 chains and topographically unchallenging; by 1862 the double-track branch became one of mixed-gauge, much of it being built on either a raised embankment or a viaduct above the flood plain of the River Thames, and by 1883 the branch was fully converted to standard-gauge.

In 1963 the branch was singled, though the half mile approaching Slough is signalled for reversible working dependent up on whether access is to or from the bay platform or the

main line.

At Slough services are currently from platform 1, which is a bay on the south side of the site, though the branch can also be reached from the main line. A feature at Slough was the triangular junction west of the station with the east and west curves both joining the main line to reach destinations to the east and west, respectively. The south to west curve was primarily used for freight services, excursions and royal trains. It consequently acquired the name Queen’s Curve or Royal Curve, the latter closing in 1970. Within the triangle an engine shed was built, coded SLO by the GWR and later, 81B by British Railways; by 1935 it had four through roads and one dead end line (usually used for locomotives requiring maintenance); closure came in 1964. There was but one intermediate station, located on the outskirts of Slough. It opened in 1929 and closure came soon in 1930, having lasted barely 13 months.

Arguably, this short branch had two of the most iconic and best-known buildings of any of the many branches in the UK – Windsor Castle and Eton College; the former giving the branch its most elite passengers and the latter, passengers who would become the elite of business and politics for many years.

Initially, a train shed similar to others on the GWR system, the station was known as Windsor, but by 1897 a very major rebuild had taken place to coincide with Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and included a much grander frontage and an interior reminiscent of Paddington.

1904 saw the suffix ‘& Eton’ added to the station’s name and in 1949 the further suffix ‘Central’ gave a distinction between the by-now Nationalised rail system’s two stations in the town. A goods yard was provided immediately to the north of the station (constructed between 1895 and 1897) and situated below the level of the passenger station. It was accessed by a steep incline and head-shunt; a separate goods shed was located to the south of the station site and it was also accessed by an incline from the branch.

Goods facilities were run down and finally withdrawn in 1964. At its peak the station had four platforms, but in 1968 platforms 3 and 4 were taken out of use with platform 2 following in 1969; platform 1 was shortened drastically in 1981, and is the sole platform in use today.

Referring to the timetable of summer 1959 there were 41 return journeys from Slough. By 2016 the equivalent timetable shows an increase to 54 return journeys despite the reduction in platforms at Windsor; passenger numbers are continuing to rise, with 1.885 million during the 2014/15 accounting period.

At various times during its history some services originated/terminated at Paddington, but currently the shuttle from Slough works efficiently and does not suffer from problems on the main-line. Royal trains ran on the branch between 1849 and 1968, (each one is listed in Christopher Potts’ excellent book entitled Windsor To Slough – A Royal Branch Line, published by The Oakwood Press in 1993). The list covers 12 pages and about 600 trains were operated.

In 1983 the ‘Royalty and Railways’ exhibition opened on Windsor & Eton Central station featuring a full-size reproduction of a 4-2-2 locomotive – No. 3041 The Queen and two period coaches. In addition 130 wax models were prepared by Madame Tussaud’s. Seven years later the exhibition was taken over by a new owner, with some alterations. It is still there today, but is beginning to look a little tired now.

Around the replica loco are numerous retail outlets, under the umbrella of the original station, catering for the needs of the town’s many foreign tourists.

Motive power on this branch has been similar to that on the other branches covered by this article, with Prairies and Panniers predominating post-Nationalisation, with first-generation DMUs such as Class 117s and 121s from 1959 and Class 165s and 166s from 1992/93.

During the pre-Nationalisation period GWR railcars worked on the branch in addition to steam-hauled services.

The future

When first proposed the modernisation and electrification of the Great Western Main Line and its associated tributaries – including the three branches under review in this feature – brought about a sense of relief that this fine railway was at last to be brought into the 21st century.

Planning and construction started in a way that appeared to the layman to be somewhat piecemeal, but as the grand reopening approached, with budgets and opening dates moving ever forward, the powers that be are beginning to abandon some of their exalted ideas.

In November 2015, the Hendy Review was published by the Chairman of Network Rail, Sir Peter Hendy. This included a few brief words that meant electrification of the line between Maidenhead and Bourne End/Marlow would be delayed. This was because there was a lack of space to accommodate a four-car electric train at Bourne End, between the trailing junction from Marlow and the buffer stops; operations with shorter units was considered too inflexible to be worthwhile.

On November 8, 2016 rail minister Paul Maynard said that to save around £150million several sections of the GW electrification would be put on hold, including the branches to Henley-on-Thames and from Slough to Windsor & Eton Central.

In the short term this means the Class 165s and 166s that are approaching 25 years in service will be required to continue to do so on these branches for longer than was originally planned.

Ultimately, electrification of all of the Thames Valley branches will happen, but the upgraded and faster service planned for and wanted by commuters and visitors to this beautiful area will have to wait – but the question is for how long?■

■ The author would like to acknowledge the help and assistance of James Davis, media relations manager, Great Western Railway, while compiling this article.

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 121 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.