Restoring Union Pacific “Big Boy” No. 4014 is an ambitious project that will take around five years to complete. Chris Milner looks at the class history and visits Cheyenne to meet UP’s senior manager of heritage operations Ed Dickens Jr, who is masterminding the complex and challenging task.

TO have seen one of Union Pacific’s “Big Boy” 4-8-8-4 locomotives at work you need to be in your mid-50s or older, considering the last revenue working of the class was on July 21, 1959.

Enthusiasts have always marvelled at their gargantuan size engine and tender weighing in at a staggering 554 tons.

The tender alone – with a capacity of 25,000 US gallons of water and 28 tons of coal – weighs nearly 153 tons, more than a BR 9F engine and tender together!

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

The 132ft 9¼in length of a “Big Boy” is the equivalent of two 9Fs double headed.

Yet, despite their size, according to Ed Dickens Jr, the 4-8-8-4 locomotives were to have been called ‘Wasatch’, after the mountain range between Utah and Idaho, which UP’s east-to-west route climbs through.

But during the construction of the locos, an unknown worker had scrawled “Big Boy” in chalk on its front. The name stuck and has become legendary in railway terminology.

The rapid growth of freight on UP’s key coast-to-coast artery, led to the introduction in 1936 of the ‘Challenger’, a capable 4-6-6-4, but trailing loads of 3,300 tons often needed double heading or helper locos (bankers) at the rear. Attaching or detaching the additional loco took time and slowed trains.

Hence a decision was made to design a new locomotive to banish the need for double-heading and banking, but in the design criteria included the need for more power and a consistent speed of 60mph away from the mountain gradients.

UP’s Otto Jabelmann led the design team that worked with American Locomotive Company (ALCO) to review the ‘Challengers’ and the team discovered that the desired specification for a more powerful loco was possible through a larger firebox, a longer boiler, a reduction of one inch in driving wheel diameter, but with the addition of two extra driving wheel axles.

Designed to be articulated like a ‘Mallet’ loco, another key design factor was the ability of the locos to run on low-quality coal from mines in Wyoming, owned by UP.

Heating problems

The first of an initial batch of 10 locos emerged from Alco’s Schenectady Works in 1941, with a second batch, also for 10, following before the end of the year. The last five were built in 1944. All were based in UP’s Wyoming division.

No. 4005 was unsuccessfully converted to run on oil, suffering uneven heating problems.

At the time of the introduction to service of the “Big Boy”, the use of diesel power in the USA was beginning to gather momentum. Diesel ‘switcher’ locos had been used in freight yards since the mid-1920s, and UP had been using General Motors ‘E’ series diesel units on passenger services.

However, it was the introduction by GM of its ‘FT’ series in 1939 that many industry observers believed would be the catalyst major railroads required to displace steam power from heavy mainline freight services.

As it happened, the observers were right, with the manufacture of just under 1,100 ‘A’ (driving) and ‘B’ (booster) units in just six years. All were sold to rival railroads, UP not being interested at the time.

UP laid down a challenge to GM’s electro motive division (EMD). It told them when it had a diesel locomotive that could match the 6,900hp performance of the “Big Boy” on the Wasatch grade in Utah, it would think about talking business. Until that day dawned, UP stuck with the “Big Boys”.

By 1945, a year after the last “Big Boy” had been built, UP was allowed to test the General Motors F3, a replacement for the FT.

Four of the 1,500hp locos in an A+B+B+A formation were tested between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, and later east from Ogden over the mountains towards Cheyenne, to compare performance with the “Big Boys”.

A year later, the UP board approved the idea of buying diesel locomotives in quantity. The writing was on the wall for the “Big Boys” and all other steam, and by 1947 the dieselisation process had begun within UP.

In fact the construction of F3 diesels, along with the successor F7 and F9 models, between 1946 and 1960, numbered 5,911, cementing their place as one of US railroad’s most numerous and most successful diesel classes.

Rising coal and labour costs were no match for the efficiency of diesels, even though towards the end of their days “Big Boys” were hauling trains of just under 8,000 tons over the Wasatch range. After that last run in July 1959, most “Big Boy’s” were stored in operational condition though to 1961, and four remained so at Green River, Wyoming until 1962.

Of the 25 built, eight survived, going on static display at various locations in the USA, some in better condition than others.

The sheer size of a “Big Boy” made it a total non-starter in respect of being owned and operated by a railfan group, and that, everyone thought in the 60s, was that.

Golden Spike

Fast forward 50 years to 2012, when news emerged that UP was looking to acquire one of the remaining locos with a view to returning it to steam in 2019 for the 150th anniversary of the Golden Spike – a celebration to mark the connection on May 10, 1869, of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit, Utah.

Internet forums went into overdrive. Enthusiasts around the world have always seen a “Big Boy” as the ‘Holy Grail’ of steam, and the thought that such a powerful steam loco might once again be seen on Sherman and Archer Hills was stuff dreams are made of.

UP examined all of the survivors, but found that No. 4014, which had been at the Southern California Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, had the most realistic chance of being put back into steam, and a purchase proposal was made.

No. 4014 had been well conserved: a 2001 report comments on how the boiler lagging had been removed to prevent moisture being trapped and rusting the boiler barrel from the outside.

The loco had been protective coated too, and all of the bearings and motions parts kept lubricated. In service, it had covered 1,031,205 miles before being donated by UP to the chapter in 1962.

As an aside, the loco has appeared in a TV commercial for fizzy pop and once had 32 schoolchildren crammed in the firebox during a TV stunt! With sale negotiations concluded in July 2013, Dickens and his Heritage Fleet Operations team made plans to extract the loco and haul it by rail back to their base at Cheyenne, Wyoming.

At the time, Ed Dickens said: “Our steam locomotive programme is a source of great pride to Union Pacific employees past and present. We are very excited about the opportunity to bring history to life by restoring No. 4014.”

In spite of the news, there were mixed views from chapter members about the sale and return to steam plan, some taking the view that its loss would reduce museum attendances.

However, in exchange, they received a former Missouri Pacific SD40-2 diesel – No. 3105 – and a Rock Island bay window caboose, plus they will get the proceeds of an excursion No. 4014 will run at some future time in Southern California.

Multi-phase operation

A ceremony to unveil a plaque on the tender is also planned to mark the “Big Boy’s” time in at Pomona, the museum’s base.

Extracting the loco from the museum was a multi-phase operation. By the time of the move proper, on November 14, 2013, the loco had been moved from the display area. Ahead of the move, Dickens and his crew re-created the chalk inscription on the smokebox of

No. 4014.

The 1,260-mile journey to Cheyenne began with the laying of temporary track across a former drive-in movie car park at Fairplex, home of the LA County Fairgrounds. No mean feat, and hard work.

UP RAILROAD

Sections of 40ft long track were moved from the back to the front of the loco leapfrog style, which allowed the loco to move forward, haulage provided by a bucket shovel. To reach the tracks of MetroLink was a distance of around 5,000ft (¾mile), to bridge with the temporary track. Progress was slow due to the track panel movement and the uneven car park.

As the loco moved, it was kept oiled, and a compressed air tank installed to provide some braking in the event the loco moved too fast.

As if the movement wasn’t complex enough, an additional requirement was to turn the loco through almost 90% on its temporary track. This would allow the loco to be extracted onto the main line tender first to allow it to be moved to the UP yard at West Colton.

This initial move from the car park to within spitting distance of the main line had taken the UP team around 10 days.

There was a break two months before 4014 was to be reunited with the main line. There were several reasons for this, one was so that the SD40 and caboose being donated could be brought to California and use the same temporary main line connection as the “Big Boy”.

It also allowed the UP guys to have a good rest and Christmas and New Year with families, returning to the warmth of the Californian sunshine later.

‘Like clockwork’

The big day came on January 26, 2014, when the MetroLink line was severed and skewed, more temporary track laid to where 4014 was resting. With planning like a military exercise, all went like clockwork, and 4014 eased onto the main line.

It was later sandwiched between SD70M No. 4884 and SD70AC No. 1996, followed by some hopper wagons as brake force, with SD40 Nos. 1596 and 1739 at the rear as the ensemble headed to Colton yard.

The “Big Boy” remained in Colton Yard two more months, before beginning a journey to Cheyenne on April 22. With a 1,200-mile journey ahead, UP sent its ‘hospital train’ from Wyoming, which are merely vehicles that act as mobile workshops and accommodation, plus a couple of vans with stores in.

Like the move to Colton, the “Big Boy” was top-and-tailed, this time by SD70M

No. 4014, the same number as the steam loco, and by 4884, the “Big Boy’s” wheel arrangement. The significance was not lost on railfans.

Moving the loco at a sedate 25mph, the trip east included stops in multiple locations and public displays in Las Vegas, Salt Lake City and Ogden, Utah.

All along the route, thousands flocked to see this steam-age leviathan as the train picked its way through city and suburb, canyon and desert, taking in its old stomping ground through Utah and over Sherman Hill.

As the “Big Boy” finally arrived in Cheyenne on May 8, right to the minute and without incident, it sounded its whistle that emitted a deep, rich tone many had never heard before.

Beaming at the new arrival in town, Ed Dickens said: “This is going to serve as the best public relations ambassador a railroad could envisage. Think about a zoo having the opportunity to bring back a Tyrannosaurus rex. How popular would that be?

This is the railroad equivalent of that.”

Even before the arrival of the “Big Boy”, preparations were beginning at the UP heritage workshops. For many years, ‘Northern’ type 4-8-4 No. 844 and ‘Challenger’ 4-6-6-4 No. 3985 were housed in the steam shop, which had a false ceiling. I

t was not until my visit last year that it was possible to appreciate (compared to a visit in 2008) the amount of space the ceiling had hidden. Here was a vast workshop that once housed travelling cranes and gave the restoration team the vital headroom they needed to lift the boiler and cab.

Health hazard

Ed Dickens explained that in order to lift 4014’s boiler, the plan was to install a new travelling crane, but removal of the ceiling had revealed 30 years of pigeon droppings, several skeletal carcasses and a mass of feathers, access for the birds being provided via a couple of broken windows.

As a health hazard, the mess needed specialist cleaners, and the upside was that the place was certainly more fragrant! New windows and heating is to be installed too.

Other requirements, once the ceiling was removed, was the need to install addition power and air lines.

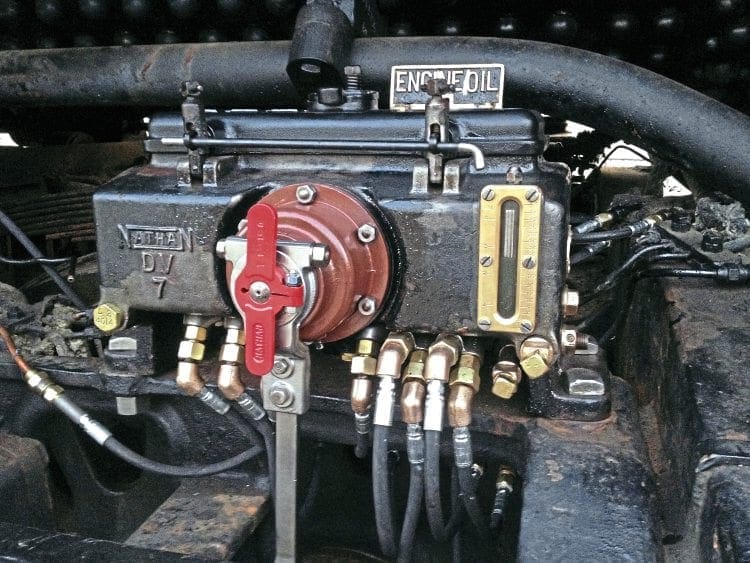

However, a year on from its homecoming, while a few individual components have been removed – air pumps, dynamos, steam and sand domes, as well as turret casings – progress is not as advanced as Ed may have wished.

More recently, the fire grates and some smokebox components have been removed. Piping in the cab has also been removed to allow the cab to be lifted from the frames.

However, the heritage team’s priority has been to complete the compulsory 1,472-day overhaul (our 10-year equivalent) and other outstanding repairs to No. 844, which has been promised for the UP president’s retirement train, so must be in A1 condition for that event in 2016.

In tandem, the installation of the crane is progressing, and at a future point, once the boiler has been lifted and placed on a flat wagon, refurbishment of the front of the loco will begin. By drawing the chassis outside the shops, work can begin on both sides of the loco simultaneously.

Next, an oil tank will be fabricated in the tender coal space, and experimental work undertaken to find how best to make the firebox arrangements for oil firing.

Ed Dickens and his team have spent time documenting the condition of the loco, and working out which parts must be manufactured new and which can be refurbished – and there’s a lot of parts in a “Big Boy”.

Many parts will be made in-house, using the well-facilitated workshops.

While the overhaul may have stuttered initially, once No. 844 is up and running, work on the “Big Boy” can be cranked up.

Having seen the loco and stood on the footplate, and spoken to some of the team, it has to rank as the biggest locomotive restoration project ever undertaken, and one the enthusiast fraternity will take to their hearts the more its progresses.

Initially, projections for the overhaul timescale was three to five years but that may now slip into the five-to-seven-year time span. It’s just too early to call, the team simply has no idea what horrors it might find as the big stripdown begins.

UP will not be drawn on costs either, Ed Dickens told The RM that it will be a quality job and not rushed, so that the restoration will last years, and the loco can seen by as many people as possible. Knowing how much care UP’s heritage team lavish on their locos, it will be a job very well done.

While no one can argue with the sentiment of a first class job, the hope is that those of us who have been lucky to see the loco in the flesh and witness the start of work, are still around in five years’ time at the end of the project to witness this steam beast doing what it does best.

Tribute to Ed Gerlits: a railwayman, gentleman, mentor and friend to railfans

ED GERLITS (“Big Ed”) was very much the mentor for Ed Dickens, and had encouraged him throughout his railroad career.

Big Ed served his own railroad apprenticeship back in the 1940s and 1950s when steam was still very much king of the railroads, and the Colorado narrow-gauge systems were largely complete.

As a result of this, he knew pretty much everything that was to be known about railroading in Colorado, and, more importantly, who was who. He helped many British railfans who had arrived in Colorado with introductions that have magically opened previously closed doors into locomotive depots and onto footplates.

Big Ed accompanied Ed Dickens to California to handle the railfan press and enthusiasts, so that the team could get on with the serious job of moving 4014.

Unfortunately, towards the end of the move in California, Big Ed contracted pneumonia and passed away. He was cremated in California, and his ashes were brought back to Cheyenne in the cab of 4014.

His favourite train-watching spot was Tabernash, on the Rio Grande’s Moffatt line, and a quarter of his ashes were scattered there. Another quarter went into the firebox on the Durango Silverton line, and the third quarter were scattered at Boston Lodge on his favourite British line, the Ffestiniog. The fourth quarter is being kept safely and part will be used in the casting of the 4014’s new regulator, while the remainder will go into the firebox on the “Big Boy’s” first run.

To the last he thought of his friends, and had stipulated that beer must be involved in any celebration of his life. Apparently, the Ffestiniog celebration certainly did him justice!

With his passing, the international railfan community and the rail industry lost one of its best ambassadors. Peter Jordan

BIG BOY’ – technical details

Built by American Locomotive Company

Build dates 1941 (20),

1944 (5)

Total built 25

Wheel arrangement 4-8-8-4

Pony wheel diameter 3ft

Driving wheel diameter 6ft 6in

Trailing wheel diameter 3ft 6in

Weight 554tons

Wheelbase 2ft 5½in

Loco length 85ft 3½in

Overall length 132ft 9¼in

Width 11ft

Heigh 16ft 2½in

Coal capacity 25 tons

Water capacity 21,000 gal

(imperial)

Boiler pressure 300lb/in2

Firegrate area 150sq ft

Cylinders 4, size 23.75in × 32in

Max speed 80mph

Power output 6,920hp

Tractive effort 135,375lb

Surviving “Big Boy” locations

4004 – Holliday Park, Cheyenne, Wyoming

4005 – Forney Transportation Museum, Denver

4006 – Museum of Transportation, St Louis, Missouri

4012 – Steamtown National Historic Site, Scranton, Pennsylvania

4014 – Union Pacific Workshops, Cheyenne, Wyoming

4017 – National Railroad Museum, Green Bay, Wisconsin

4018 – Museum of the American Railroad, Frisco, Texas

4023 – Kenefick Park, Omaha, Nebraska

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 121 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.