Newspapers were carried on trains for a century and a half between the 1830s and the 1980s. Consultant editor Nick Pigott, who worked as a Fleet Street journalist for 13 years, tells the little-known story of the overnight services that rushed the news from press to public.

ANYONE returning home by train from a late night in central London prior to the late-1980s will have seen them… large vans racing into the main rail termini, their tyres screeching as they turned the tight corners into the parcels platforms and sped towards the open doors of waiting trains.

On their sides were emblazoned in huge letters names such as Daily Express, Daily Mirror, The Times, The Guardian.

Those were the days when the capital’s main line stations echoed to the frenzy and flurry of the nightly Fleet Street miracle – the production and distribution of millions of national newspapers to a population eager for the latest news.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Whisked hot off the presses, they would be packaged into large bundles, thrown into the backs of the vans and rushed to main stations such as Euston, St Pancras, Waterloo and Paddington.

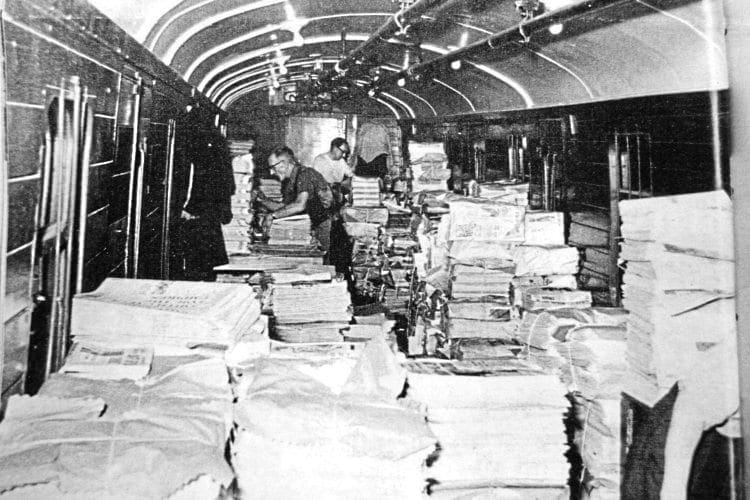

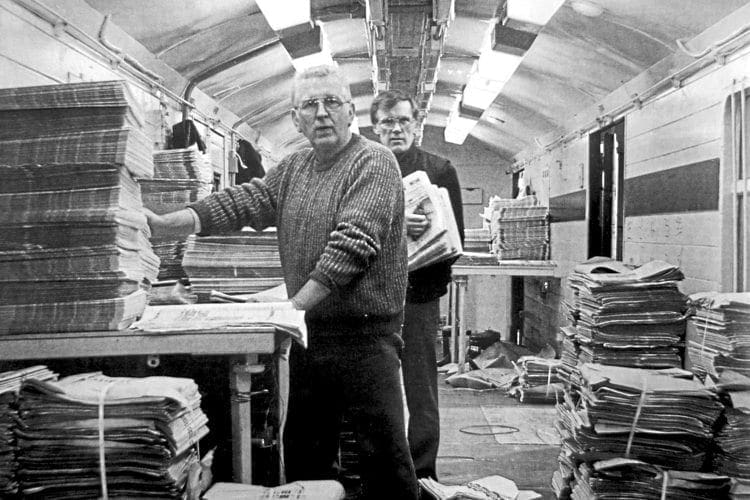

Working at top speed in order not to miss the trains’ all-important departure times, teams of men would sling the bundles into special newspaper train carriages, some of which contained on-board staff whose job was to sort the bales into order en route in much the same way as Travelling Post Office train workers.

Sorted for distribution and affixed with the address labels of provincial wholesalers or newsagents, the papers would then be dropped off at the various stations along the line. In some small towns, it was not unknown for a bundle or two to be thrown onto the platform as the train sped through!

Exciting

It was all very exciting, but the last decade in which it could be witnessed was the 1980s. After that, the replacement of ‘hot metal’ printing methods by digital technology meant that pages no longer needed to be printed in the traditional publishing centres of London and Manchester.

Instead, they could be transmitted electronically to regional satellite presses close to motorway junctions for onward distribution by road. Well before then, of course, radio and TV had already started to make massive inroads into the circulations of papers, signalling an end to the profitability of dedicated newspaper trains. It all came to an end with the running of the last service in 1988.

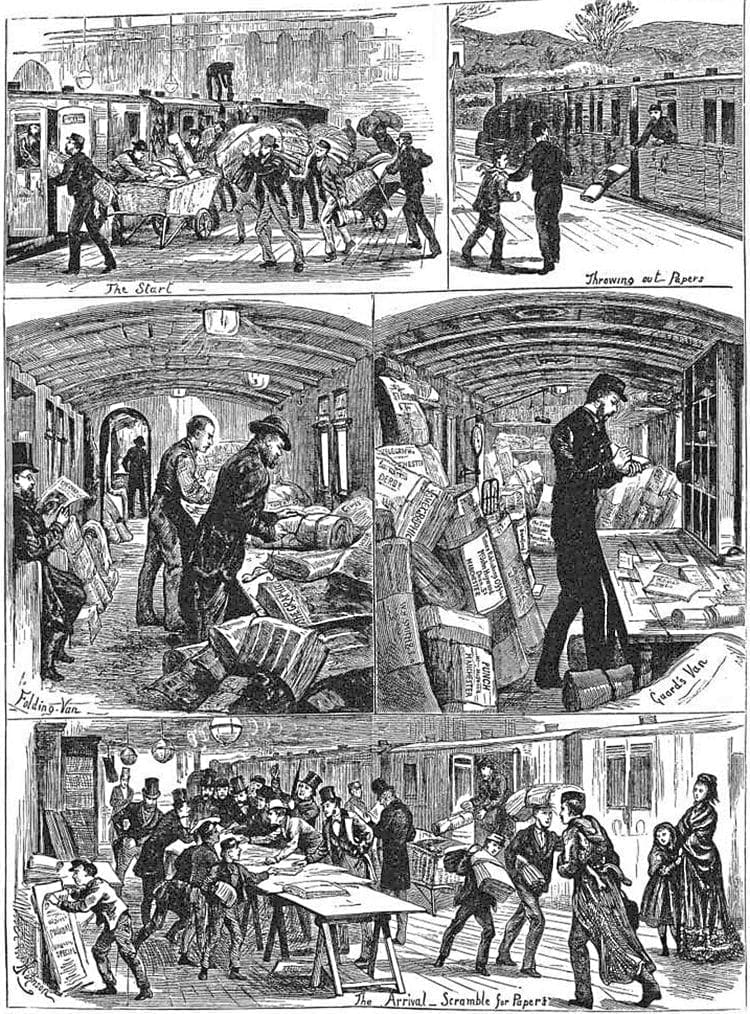

In the 19th century, papers were the only realistic way of disseminating large amounts of news and information to the masses and their conveyance from presses to provinces had been a lucrative business for stagecoaches and mail coaches long before the first passenger railways began to appear in the 1830s.

The world’s first daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, was founded in London in 1702 and although it didn’t survive into the railway age itself, it proved the catalyst for a huge national industry, which by the mid-19th century included titles such as The Times (launched in 1788), The Observer (1791), the News of the World (1843) and The Daily Telegraph (1855).

However, the stagecoaches were so slow – less than 15mph on average with frequent stops to change horses – that the news was often two or three days old by the time it reached its further-flung readers.

Regional evening and morning titles such as the Yorkshire Post, Glasgow Herald and Manchester Guardian – all of which were in existence before the advent of passenger trains – had a distinct advantage over the nationals.

The dawning of long-distance railways was thus a dream-come-true for the nation’s leading press barons and news distributors and it’s no exaggeration to say that the development of steam traction and the rail network enabled Britain to have a truly national press for the first time.

The pioneering agreement to convey journals by rail was signed by the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1831 – just a year after the line opened – and when the Grand Junction Railway came into operation six years later, a newsagent by the name of Mansell & Co tied up deals with that company and the shortly-to-be-completed London & Birmingham Railway for the transport of papers along the West Coast Main Line to Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool.

The fledgling railway companies were only too keen to seize business from the stagecoaches and treated the newspapers as a form of parcels traffic, rather than goods. This enabled them to offer faster speeds at rates undercutting those of their slower rivals.

Even the word ‘express’, with its popular if not strictly correct association with newspaper printing (ex-press), was borrowed from the stagecoach industry to refer to a fast service.

Astonishing

One of the biggest players in the news trade then (as now) was the firm of WH Smith, which had been trading under that name since 1828 and was busy planning the opening of numerous station bookstalls (see The RM, Nov 2014). From 1837, Smiths began tying up its own distribution deals with many early railway companies and in February 1848 showed the world what was possible by chartering a special train to deliver papers containing news of a Government budget speech.

It ran from Euston to Glasgow via Rugby, Milford Junction, York, Newcastle and Edinburgh, and the whole 476-mile journey, inclusive of stops and engine changes, was accomplished in less than 10½ hours at an average speed of almost 50mph – even more astonishing given that the newspapers twice had to be transferred from one train to another as the rail bridges across the Tyne and the Tweed had not then been opened.

By the time the Great Northern Railway’s section of East Coast Main Line opened throughout as a relative latecomer to the trunk network in the early-1850s, Smiths and its rival distributors had abandoned almost all their stagecoaches.

An aspect of this not widely appreciated today is that canals weren’t the only forms of transport eclipsed by the railways, for once the coach operators had been put out of business, there was little reason for turnpikes and other main roads to be maintained properly as only carts, horse-riders and pedestrians needed to use them.

Many became overgrown and dilapidated until the advent of motor vehicles 50 or so years later.

At about the turn of the 20th century, the national newspaper industry grew still further with the arrival of a trio of newcomers destined to become massive sellers – the Daily Mail in 1896, the Daily Express in 1900 and the Daily Mirror in 1903.

Within a relatively short period, those three big hitters had added millions to the industry’s overall daily sale.

Literacy in Britain had grown immensely during the 1800s thanks to improved education, but the railways had played a huge part in bringing that about by providing the masses with affordable daily reading material; in the three decades between 1820 and 1850 alone, the total sale of papers rocketed by more than 400%.

All that newsprint weighed hundreds of tons and in later years it became even heavier at weekends with the advent of supplements and bulky Sunday editions.

Trains were perfect for such traffic, not only because of their size and speed but because they could run through the night when the network was virtually free of passenger services. At first, the papers were carried in vehicles attached to late-evening passenger trains, but as the business grew larger and more lucrative in the latter part of the 19th century, services began to be run solely for the news trade.

An advantage of this was that passengers weren’t delayed by any hold-ups in sorting and unloading the bundles.

Some publishing companies, such as The Times, tried to persuade railway operators to run ‘exclusive’ trains carrying only their own title, but it wasn’t until 1872 that the proprietors of The Scotsman newspaper managed to get the North British Railway to run a 4am special from Edinburgh to Glasgow every day.

So successful was it that two more dedicated services, one to Perth and one to the Borders via the Waverley route, were introduced.

Exclusive

Special trains for The Times began shortly afterwards, and in 1899 the Daily Mail arranged with the then-new Great Central Railway for an exclusive 2.30am run from Marylebone taking news of the Boer War to the citizens of Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield.

The Scotsman actually holds another special place in the story of papers and railways, for a new headquarters building it moved into in 1904 contained its own sidings below the printing presses to enable copies to be transferred directly to trains and to allow newsprint and ink supplies to be brought in by train during the day.

With the ‘Express’ and ‘Mirror’ entering the national scene at about that time and, later in the 20th century, the Daily Sketch, the Daily Worker and several new Sunday papers, the railways were able to capitalise on this lucrative traffic and hold on to it for a great many decades.

Only during short periods of the First World War and the General Strike of 1926 did Smiths turn temporarily to motor transport, but road vehicles in those days were no match for trains until the widespread introduction of fast highways and lorries.

The Second World War threw up some horrifying challenges and a documentary film entitled Newspaper Train, made by the Ministry of Information in 1942, shows how the services continued to run during the Blitz when lines in London were frequently being destroyed by Nazi bombs.

It tells the story of one that was attacked by an enemy fighter plane while steaming through Kent and contains remarkable footage of a Ramsgate newsagent picking the aircraft’s cannon bullets out of a bundle of papers!

The ‘Big Four’ period between 1923 and 1947 and the early part of the nationalised British Railways era probably represent the pinnacle of newspaper trains, but they constituted a major component of railway life for no less than a century and a half.

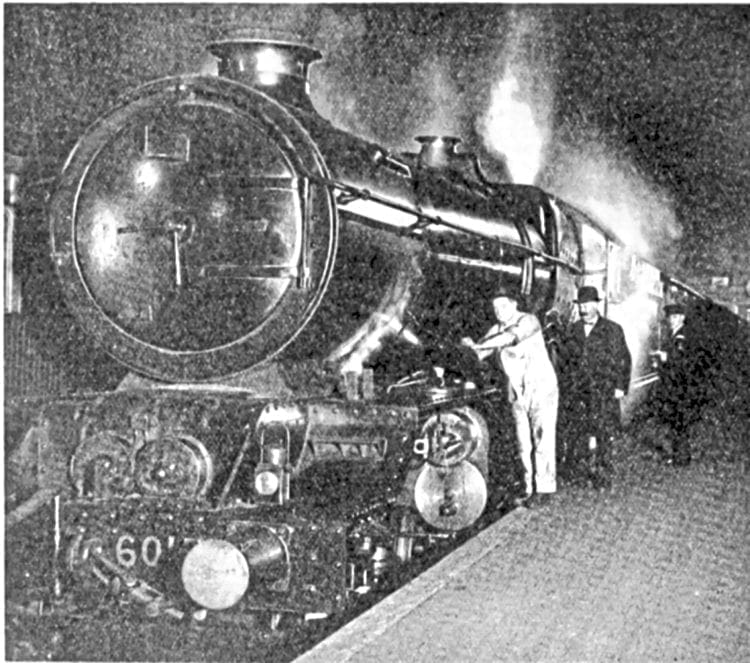

The haste with which they were worked was literally breathtaking at times, not only for the staff, who could often be seen running around the stations, but in the speed of the trains – so much so that the 12.50am Paddington-Plymouth, with a timing of 140 minutes for the 143 miles to Taunton, was described in 1934 as ‘the fastest newspaper train in the world’. Small wonder with a powerful ‘King’ class 4-6-0 at the head of a rake of vans!

The reason why travelling sorting staff were required on board newspaper trains was because each of the bundles that arrived at the termini contained only one title, there simply having been no time to merge them with others after whisking them off the press and tying them up with twine ready for rushing to the stations.

Sorting and re-stacking them into parcels of varied titles suitable for each individual newsagent had to be done between that stage and arrival at their destinations.

Until the mid-Victorian era, the situation was even more problematical because many newspapers in those early days had to be folded and assembled by hand into readable form and were often not ready for dispatch until the following morning. In the spring of 1875, however, W H Smith and the proprietors of The Times realised that assembling the sheets en route overnight would put those wasted hours to good use and speed up the process of getting morning papers onto provincial breakfast tables.

Deadlines

As a result, so-called ‘packing’ or ‘filling’ coaches were introduced between Euston and Birmingham on the London & North Western Railway. Equipped with lighting and tables, the vehicles enabled the pages to be worked on so that people in the West Midlands could be reading their paper not much later than those in the capital.

Within a matter of weeks, the Great Northern Railway, Midland Railway and other newspaper owners had followed suit and it wasn’t long before teams of men working for Smiths and other provincial wholesalers were travelling overnight on all the main lines, handling the many different publications.

Their job was to break the bales down and make up new bundles – for example, 50 copies of The Times, 30 of the Telegraph, 10 of the News Chronicle and so on. Doing that to constant station deadlines numerous times a night on a swaying, jolting train of hard-riding vans travelling at rapid speed was no easy task and called for quick work and great concentration.

During a typical night in the mid-1960s (the period in which The Sun newspaper was launched), trains from Paddington alone would collectively clock up many hundreds of miles, reaching locations such as Bristol, Cardiff, Carmarthen, Plymouth and Oxford.

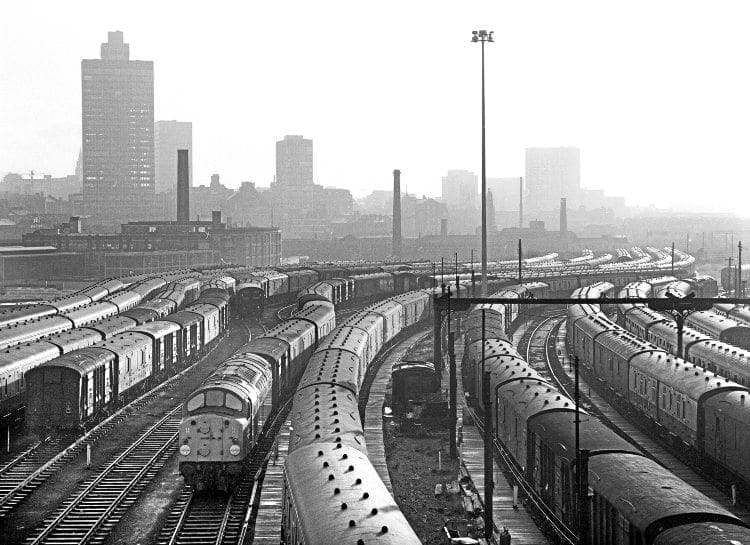

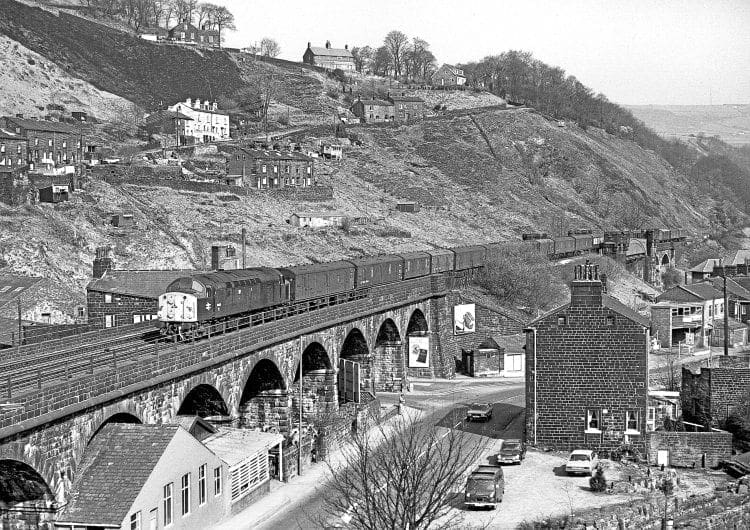

From Manchester Victoria/Exchange there were numerous overnight services to the likes of Liverpool, Blackpool, Leeds, Crewe, Stoke and across to Cleethorpes, Hull, York and Newcastle. The trains were often so heavy that in steam days the eastbound ones required a banker to get them up Miles Platting bank.

Trains from King’s Cross also served Newcastle en route to Scotland, while Euston, St Pancras, Liverpool Street, Marylebone, Waterloo, Victoria, London Bridge and smaller stations such as Holborn Viaduct (the nearest main line terminus to Fleet Street) served the rest of the nation. Train-splitting, with detachments and attachments en route, complicated the situation even further, especially in the earlier years.

At its peak, British Railways in the 1950s/60s was running more than 50 dedicated newspaper trains every weekday – and Saturday nights/Sunday mornings were even busier, with 75 services conveying heavy Sunday editions… three-quarters of the country’s entire weekend newspaper production.

The fact that Sunday papers went to press earlier than the dailies (only needing to wait for the football reports) meant they could be loaded onto trains and be dispatched mid-evening and that compensated somewhat for the increased loads.

Britain’s other major national newspaper printing centre in those pre-digital days was Glasgow, but certain titles were printed only in London and those had to be sent north either by air or via the 20.33 Euston-Inverness and Lairg train.

During the week, news trains often carried parcels and mail as well, but at weekends, the extra loads usually prevented such sharing. The lengths of trains varied enormously over the ages, some formed entirely of dedicated vehicles while others might have had just one or two vans coupled to a timetabled passenger service (in which case, of course, they would officially have been passenger trains carrying newspapers rather than the other way round.)

Night shifts

Departure times varied tremendously too, anything between 21.00 and 05.00 on a weekday, depending on distance. Not surprisingly, they were popular with engine crews and other railwaymen as a means of getting to and from work when on night shifts.

The rolling stock for newspaper services in later years usually consisted of GUV (General Utility Van) and BG (Brake Gangway) types of the NLV, NLX, NMV, NCV, NCX and NFV classifications (the ‘N’ in this case standing for Non-passenger rather than Newspaper).

Four-wheeled CCTs (Covered Carriage Trucks) were also used, although not in passenger trains after the banning of non-bogie vehicles from such services, while on the Western Region, ‘Siphon’ vans were commonplace.

On the modern traction front, diesel parcel units and even some Class 308 electric multiple units saw service.

The preponderance of (usually grimy) vans meant that it was not always easy for a lineside observer to differentiate between a newspaper working and an ordinary parcels train, but in the case of some of the longer-distance corridor formations, it was occasionally possible to do so by the presence of a BSK or similar seating coach marshalled into the rake.

This would not only provide toilet facilities in addition to those found in some of the vans, but would allow the staff to relax and get some sleep if they finished their duties before the end of the journey.

It wasn’t unknown for such carriages to provide an unofficial early morning Sunday service for late-night revellers who’d missed their last Saturday night train… the staff usually turning a blind eye if the service wasn’t one of those advertised in the passenger timetable.

External recognition matters for linesiders improved somewhat in the BR diesel era when packing carriages and converted DMUs began to carry the word ‘Newspapers’ on their bodysides. Some of the latter also had roller-shutter doors.

Popular

The nocturnal nature of the trains in the years before digital photography mean that comparatively few photos exist as they either had to be captured on film in illuminated termini before departure, in daylight when approaching their destinations in mid-summer, or when returning empty the following morning or afternoon.

A particularly popular run among enthusiasts was the return working of empty vans between the carriage sidings of Heaton and Manchester Red Bank, which usually loaded to more than 20 vehicles and was often double-headed.

In BR days, the average size of crew for a news-packing train was between five and six and it is worth taking a typical night’s shift for W H Smith’s Nottingham warehouse team in 1967 as an example:

Their ‘day’ starts when they board a late evening passenger train to St Pancras, travelling the 120-plus miles to the capital in comfort and then walking to Euston (as this particular diagram is to travel via Northampton).

The vehicles in which they are due to work will have been sent back south earlier in the day as empty stock or as part of a normal parcels train.

Just before midnight, the first road delivery vans begin to arrive crammed full of the next day’s editions. These are stowed on the train in the order in which the on-board team will need to process them during the journey.

By the time the train is ready to depart an hour and a half later, there will be almost 20 tons of papers in the two sorting coaches, but the men get straight down to work as soon as they enter the train, breaking open the early bundles and sorting the papers.

All around on the platform people are milling around, most working, some just hoping to cadge a free paper!

Everything is hectic, frenetic and tightly timed. If a delivery driver has been late and missed his slot at the presses, his road van will have lost its place in the queue with knock-on implications all the way down the supply line, so if any papers are missing, a quick phone call is made to the relevant publisher and, if there’s time, another van – or perhaps even a taxi – is sent speeding off to the station.

At 01.40 on the dot, the train pulls out punctually and for the next three hours, the men don’t get a minute’s rest as they sort and collate the load according to the various newsagents’ requirements, untying bundles, transferring the relevant papers, then re-tying and labelling them with addresses so that each new parcel is ready to be immediately off-loaded.

It’s not even possible to learn the job by rote as newsagents’ orders change every night.

Physical

It is hard to believe that by the end of the journey this crew alone will have handled 130,000 papers – more than 25,000 per man – and wrapped and tied more than a thousand bundles, not to mention the tough physical work of heaving the heavy bales backwards and forwards along the carriage and up and down onto tables.

In some cases, the weight will have been increased by the inclusion of magazine parcels, but those will have been sorted and labelled by wholesalers the previous day.

After a run at speeds of up to 75mph (a diesel having replaced the electric at Northampton for the second half of the journey via Market Harborough), the train pulls into a dedicated siding at Nottingham at 04.15 to be met by no fewer than 30 road vans, all backed up with their rear doors ready open.

During the night, the sorted bundles have been carefully stacked next to the 10 external doorways according to which district they are destined for. As the train draws carefully to a halt, the reason for this becomes apparent, for the doors line up exactly with the first 10 vans, enabling the papers to be thrown straight from one to the other to save precious minutes.

Within a quarter of an hour, the carriages have been emptied and less than an hour later, every newsagent’s shop and bookstall within a 15-mile radius of Nottingham has had its orders delivered by vans. Paper delivery boys and girls earning a bit of pocket money will do the rest.

It would be interesting to know how many members of the public were really aware of the enormous efforts that went on to get their paper onto their doormat every morning and simply took its arrival for granted?

Nocturnal

To support this largely unseen nocturnal operation, a complex network of wholesale houses existed throughout the country, some owned by Smiths, some by competitors such as Surridge Dawson.

Almost every major town and city had at least one and they were more often than not at, or close to, railway stations. Well into the British Rail AC electric era, small towns like Hemel Hempstead, in Hertfordshire, were still being served by overnight news trains.

Because of the difficulty of getting road vehicles onto the platforms of most through stations along the routes, such deliveries would normally be loaded first into ‘Brute’ trolleys or battery-powered vehicles for transfer to waiting vans outside, but in a few places, the wholesale house itself was physically rail-connected with its own dock siding.

Such a depot was Broad Green, east of Liverpool, which Smiths opened in 1967 to serve almost 500 retail outlets in a 42-square mile area.

The depot was served by a nightly train from Manchester, which would shunt two bogie vans in at about 04.00 before continuing to Lime Street terminus with supplies for the city centre shops.

The relatively short distance from the Manchester printing presses negated on-train sorting, so the staff at Broad Green would unload 10 tons or so of papers onto a platform-level conveyor belt and get to work sorting and re-packing them inside the depot.

The first blow to the newspaper train industry fell in the 1980s when The Guardian decided not to renew its contract with BR and switched to road transport, but by far the biggest nail in the coffin was the move of Rupert Murdoch’s News International (publishers of The Sun, The Times and News of the World) from Fleet Street to new-tech printing premises at Wapping in 1986.

Murdoch knew the rail unions were threatening to ‘black’ papers printed in Wapping in protest at print job losses and had therefore signed advance contracts with road hauliers for the dispatch of papers in articulated lorries.

BR sought compensation for breach of contract but the damage had been done. No longer would those market-leading titles find their way to readers via the London stations.

That move took a large chunk out of BR’s £125million-a-year paper and magazine distribution business – and matters were to get worse the following year when it lost another big contract with Mirror Group Newspapers.

Back in its heyday, news traffic had been described by eminent transport historian Professor Jack Simmons as “a commodity par excellence” for railway companies, but with the market’s biggest players gone, the economics of rail-based distribution began to collapse.

A number of nightly trains continued to run for the remaining traffic, but with the income continuing to haemorrhage, BR undertook an assessment and concluded that the business was no longer worth pursuing. Overnight sorting of newspapers in dedicated trains thus officially came to an end on July 9/10, 1988.

Sleeping

A handful of vans remained in use in the south for a few weeks, but they had all gone by November. After that, a few small supplies – tiny in comparison to the huge bulk loads of the past – continued to be conveyed in the guard’s vans of sleeping car trains and ordinary passenger services, but by the time rail privatisation came sweeping in like a new broom in the early-1990s, it was all over. Today, wholesale houses across Britain continue to sort papers and periodicals, but the station platforms of Britain are no longer bustling hives of activity in the small hours of the night. Instead most are locked up and deserted as the lorries that took their work pound ceaselessly up and down the motorways… just one more example of a commodity lost to the railways. ■

Today, wholesale houses across Britain continue to sort papers and periodicals, but the station platforms of Britain are no longer bustling hives of activity in the small hours of the night. Instead most are locked up and deserted as the lorries that took their work pound ceaselessly up and down the motorways… just one more example of a commodity lost to the railways. ■

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 121 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.