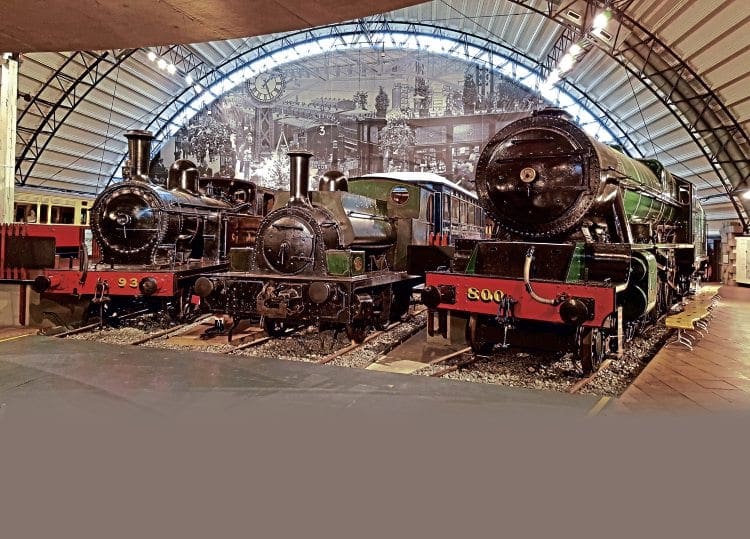

The Ulster Folk & Transport Museum at Cultra, near Belfast, is home to the largest collection of locomotives, rolling stock and trams not just in Northern Ireland, but in the Emerald Isle as a whole. Gary Boyd-Hope looks at the core collection and its origins, without which preservation in Ireland would be considerably poorer.

IT WAS the poet William Blake who said: “Hindsight is a wonderful thing but foresight is better”, and where Irish railway preservation is concerned, the foresight of the old Belfast Corporation’s museum committee was the best there was!

For if it had not been for the efforts of the enlightened souls within the committee in the immediate post-Second World War years, the number of surviving ‘treasures’ from the railways and tramways on both sides of the border would present a far bleaker picture than it does today.

Britain had been fortunate that the old London & North Eastern Railway had set aside locomotives for preservation in its York railway museum, which was subsequently inherited and developed by the British Transport Commission after Nationalisation.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Yet there was no similar provision across the Irish Sea. In Dublin the 1847-built Great Southern & Western Railway 2-2-2 No. 36 had managed to evade the cutter’s torch long after its 1874 withdrawal, but it really was an isolated example – and its tender did not survive.

The Republic of Ireland’s Transport Act 1944 led to the formation of a new unitary transport authority – Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ) – which came into being on January 1, 1945. It soon made its intentions clear with a programme of mass dieselisation, which would eradicate steam from the network by April 1963. Similarly, Northern Ireland’s transport network came under the control of the Ulster Transport Authority (UTA) in 1948, ultimately leading to a mass shrinkage of the province’s railway map owing to line closures and service withdrawals.

It was against this backdrop the Belfast Corporation, together with a few sympathetic railway officials and curators at Belfast Museum & Art Gallery, decided to take action. It was clear public transport in the north and south was to undergo substantial change, and it was agreed the corporation should keep representative examples from the past, particularly trams and railways. The fact the railway network in Ireland was mostly developed before the partition in 1922 made it logical to consider Ireland as a whole when thinking of railways, rather than just collect artefacts from Northern Ireland.

Read more and view more images in the August issue of The RM – on sale now!