One of the most surprising developments of recent years is the return of many ex-BR diesel locomotives to the main line. Ben Jones talks to some of the major players in this ‘re-emergence’ and finds out why it is happening.

FLICKING through the pages of The RM every month, one of the most obvious trends of the last couple of years is the remarkable revival of many vintage diesel locomotives.

From 60-year-old Class 20s delivering new Underground trains to utterly transformed Class 73s hauling Scottish sleepers, dozens of machines have been liberated from scrapyards and preserved railways to take up a second (or even third) career on the main line.

While this is a real boon for railway enthusiasts, bringing extra interest and variety to the contemporary UK scene, commercial railway companies must have a clear economic and operational case for taking this route – put simply, these machines have to earn their keep in the modern world.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Since the early years of privatisation in the late-1990s, preserved or privately owned diesels have sporadically returned to the main line for railtour or short-term ‘spot hire’ work, but the recent renaissance of ex-BR motive power is a response to various factors affecting contemporary freight and infrastructure operators.

Direct Rail Services (DRS) set the precedent for reviving older diesels in 1995-98 when it acquired 15 Class 20s and had them extensively modernised by Brush (20301-305) and RFS(E) (20306-315) for hauling nuclear flask trains.

In the absence of any new type of low/medium power diesel locomotive, the ‘20s’ offered a quick and proven solution to the new operator’s go-anywhere requirements.

A shortage of new locomotive designs to the UK loading gauge remains an issue today, especially now that Class 66 production has finally ended. Stadler’s 3,750hp Class 68 and General Electric’s 3,820hp Class 70 are the only straight diesel locomotives currently on offer to UK operators, and with a Route Availability rating of 7 (RA7), both designs are barred from large parts of the network – especially at its extremities.

Add in the high leasing costs of complex, powerful machines, costing around £3-4million each, long lead times for new orders and strict emissions rules for diesel engines, this makes machines with ‘grandfather rights’ for operation on the network start to look more attractive.

Depressed sales

A similar situation exists across mainland Europe, where sales of new diesel locomotives have been depressed for more than a decade.

Although the ‘big three’ train builders – Bombardier, Siemens and Alstom – all offer diesel versions of their main locomotive ‘platforms’ (‘TRAXX’, ‘Vectron’ and ‘Prima’, respectively), sales are far outweighed by their electric equivalents.

With a limited pool of customers, and comparatively low sales potential in the UK, there’s little incentive for the big rail groups to invest in designing bespoke locomotives for British operators. The great success of the EMD Class 66 lay not just in the fact that it was reasonably cheap, reliable and could be delivered fairly quickly, but also because there was nothing else on offer.

Operators looking for modern small or medium power diesels in Europe can call on alternative suppliers such as Vossloh Locomotives in Kiel and CZ Loko of the Czech Republic, but to date these have shown no obvious interest in the UK market.

A version of the Vossloh DE18 – a single-cab diesel-electric available in the 1,100 to 1,800kW power range (1,475hp to 2,400hp) – built to the British loading gauge could be an extremely useful tool to replace ex-BR Type 1 to 3 diesels, but we may have to wait some time for such a machine to come along.

In the meantime, several rail engineering companies have carved themselves a lucrative niche by offering thoroughly overhauled and modernised locomotives built between the late-1950s and late-1970s.

Short-term capacity

In many cases ‘classic traction’ has been called back to the front line to provide extra short-term capacity during traffic peaks, or to free more modern and powerful locomotives from lightweight or short-distance workings, where they are not being used to their full potential.

This work includes Network Rail test and infrastructure management (IM) trains, rolling stock moves and new train deliveries, on-track plant transfers and short-term or one-off freight contracts.

GB Railfreight has been a prime example of this, hiring Class 20s to deliver new Underground trains from Derby to London and using ex-Riviera Trains Class 47/8s on local sand trips around Doncaster. In both cases, older machines provided an ideal, cost-effective solution and freed Class 66s for more mainstream intermodal or bulk freight work.

In contrast, DRS has employed its fleet of modernised ex-BR diesels on a wide range of work, from lightweight nuclear trains to heavy Anglo-Scottish intermodals on the West Coast Main Line.

DRS’ fleet has constantly evolved since the late-1990s, drawing in second-hand Class 20s, 33s, 37s, 47s and 57s, but also introducing modern Class 66s and 68s (and soon Class 88 electro-diesels) on the most demanding duties.

Since 2015, it has also had to return a number of electric train supply- (ETS) fitted Class 37/4s to passenger work with Northern and Greater Anglia because of DMU shortages. These two operations have created a huge amount of interest among the enthusiast community, but have also forced DRS to acquire and revive several extra ‘37/4s’ – some of which were not expected to run again.

As an added bonus, some of the company’s Class 37/4s have been returned to their original BR large logo blue livery, complete with Eastfield depot West Highland terrier emblems. In addition to Nos. 37402/405/409/415/419/423/425, DRS has invested hundreds of thousands of pounds per locomotive in heavy overhauls and modernisation for Nos. 37401 Mary Queen of Scots in 2014 and, more recently, 37403 Isle of Mull, 37407 and 37424, which had been stored in the open air for many years after withdrawal.

Specialist refurbishment

These locomotives were prepared for their return to traffic by LORAM (formerly Rail Vehicle Engineering Ltd), which is a major player in the specialist refurbishment and overhaul of older rail vehicles. In recent years it has expanded its operation at the former BR Railway Technical Centre in Derby to cope with demand from customers, including Network Rail, First Great Western, DRS and Colas Railfreight.

LORAM UK commercial director Andy Houghton has seen operators recently turn to his company to help meet their traction requirements. He says: “It is a cost effective method of creating reliable, fuel and maintenance efficient locomotives.

“Operators can gain the advantages of modern equipment without the huge costs involved with the introduction of a new locomotive.”

Other industry sources suggest that a full ‘heavy general’ overhaul on, for example, a Class 37 can cost in the region of £750,000, so while it’s not a cheap option, it costs significantly less than buying new, and it brings the added advantage of using proven, reliable (if outdated) equipment.

While much of the cost centres around overhauling ageing power units and repairing years of neglect and corrosion to bodywork, there also has to be a significant investment in up-to-date signalling, safety and monitoring equipment.

For locomotives that have, in some cases, been off the network since the late-1990s, modernisation work includes the installation of Train Protection & Warning System (TPWS), On-Train Monitoring & Recording (OTMR), Driver Safety Device (DSD), and GSM-R telephone equipment costing tens of thousands of pounds, plus modern headlights and new high-impact windscreens with toughened safety glass and reinforced frames.

According to Andy Houghton, overhaul costs can vary depending on the scope of the re-engineering and customer requirements. In the case of the two ‘Ultra’ Class 73s re-engineered by RVEL/LORAM in 2014/15 to replace Class 31s on Network Rail’s ultrasonic test trains, the donor locomotives were stripped back to bare metal bodyshells and rebuilt from the ground up.

Modern electronics

“You need to consider the new control systems that are required with the new engines, traction systems, driver controls, brake systems, and even such things as air conditioning,” Mr Houghton elaborates.

The rebuilding of Nos. 73951/952 went much further than most projects, replacing the original 600hp English Electric power unit with two 750hp Cummins QSK19 engines (as used on Class 185/220-222 DEMUs) and sophisticated modern electronics to create a 1,500hp ‘genset’ unit capable of working anywhere on the British network.

Andy Houghton says: “Class 73 was chosen due to its ‘go-anywhere’ capabilities. It has good route availability. There were also a number of spare locomotives available for re-engineering at the time we were looking at it. However, the ‘Ultra’ gen-set technology can be applied to almost all existing locomotive platforms.”

Will there be any more ‘Ultra 73s’ to follow NR’s Nos. 73951/952?

“We are hopeful the trend will continue and we are already working on new enquiries for the technology we have used on the Network Rail ‘Ultra’ Class 73s,” he added.

Redundant and preserved Class 73s also provided the basis for another remarkable re-engineering project that has taken the electro-diesels far beyond their original Southern Region home.

In 2014-16, Brush Loughborough rebuilt 11 locomotives for GB Railfreight, including two of the prototype ‘JA’ batch (Nos. 73005/006) dating from 1962. Again, the original EE power unit was replaced, in this case with a 1,600hp MTU4000 engine, and modern control electronics.

Nos. 73961-965 retain their 750V DC third-rail capability and are used for Network Rail engineering trains on the Southern Region and beyond, while Nos. 73966-971 are allocated to Caledonian Sleeper services, working from Edinburgh to Aberdeen, Fort William and Inverness. The Scottish ‘73s’ no longer have third-rail shoegear, but have a higher ETS rating for powering sleeping car trains and greater fuel capacity.

While they have suffered from teething troubles, including alternator problems, they provide a capable, if unconventional, solution to powering the diesel legs of the CS operation. One will even visit the Czech Republic this year to assist with the testing of new Mk5 sleeping car vehicles at the Velim test centre, near Prague.

‘Versatile’ Class 37

Withdrawals started in the late-1980s, but the privatised railway has so far proved unable to manage without that most versatile of mixed traffic diesels – the English Electric Class 37s. DRS has, of course, been the most high-profile user over the last 15 years, but ex-EWS machines continue to reappear in new guises, along with former DRS machines managing a third (or even a fourth) lease of life with new operators.

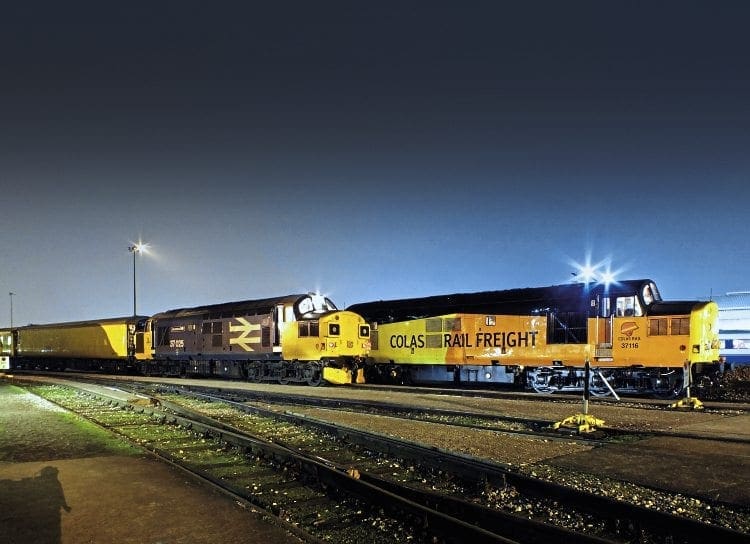

Several former ‘wrecks’ and preserved Class 37s have recently returned to the main line with Colas, powering NR test trains all over the country.

Carrying a colourful selection of liveries, from original BR green No. D6757/37057 to InterCity No. 37254, not to mention Colas’ orange/yellow house colours (Nos. 37099, 37116/175, 37219, 37421), most have undergone expensive overhauls to bring them up to the necessary standard.

While some have been acquired by Colas from preservation groups, others are on long-term hire, such as No. 37025 Inverness TMD. Colas also has Nos. 37146/188, 37207 and 37901 under overhaul or awaiting repair.

Having started by hiring in traction from other companies, Rail Operations Group (ROG) now has its own fleet of ex-BR locomotives, too – buying five Class 47/8s from Riviera Trains (Nos. 47812/815/843/847/848), hiring Nos. 37800/884 from Europhoenix and acquiring No. 37608 from DRS in 2016.

The two ‘heavyweight’ Class 37/7s have a fascinating recent history, having been exported to Spain by EWS in the early-2000s to haul construction trains on new high-speed lines, then stored awaiting disposal and finally repatriated, repaired and restored to main line condition by Harry Needle Railroad Co (HNRC) at Barrow Hill (No. 37884) and UK Rail Leasing (No. 37800).

HNRC has been active in the UK locomotive engineering and hire market for more than two decades, and has become a market leader, competing with multi-national giants such as Wabtec and LORAM, despite having just 32 staff. HNRC supplies overhauled industrial shunters and ex-BR Class 08s, 20s, 37s and 47s for a variety of customers, including DRS, Colas and Network Rail.

‘Value for money’

“We’ve worked with all the freight operators, and others besides,” Harry tells me in his office at Barrow Hill.

“We’ve never had one of our locos returned, never had any complaints and the Class 37s we rebuilt for Network Rail (Nos. 97301-304) have proved to be the best value-for-money locos ever overhauled.”

As someone whose core business is built around restoring these older machines, why does he think more and more are making a comeback?

“Rebuilding a Class 37 or a Class 47 will cost you around £600,000, but that will put it back on the main line for 10 years, whereas a new Class 68 could cost you £4million. It’s more cost-effective and it gives you a proven, reliable machine that is compliant with the modern railway.

“We can also offer a ‘power upgrade’ if the customer wants it – for example we can replace the English Electric power unit in a Class 37 with an MTU4000 engine, similar to those now used in HST power cars. De-rating it to 1,750hp will prolong the engine’s life, too.”

He continues: “I think these locos have got at least another 15 years left in them. It’s not cost-effective to build new RA5 locos to our bespoke loading gauge. Look at the ‘08s’. DB Cargo has just sold off its fleet but there’s still a need for shunting locos at many places.

With a changing railway business, more investment in new lines and HS2 on the horizon there are probably more opportunities for us now than there have ever been.”

The award for greatest survivors though must go to the Class 20s, which celebrate their 60th anniversary this year. HNRC owns 22 of the class, eight of which are passed for the main line and used by GBRf, and also hires others to industrial users such as Lafarge and Tata/British Steel.

Robust, reliable, cheap to run and able to go almost anywhere, the ‘Choppers’ have once again proved their worth, especially when working as a 2,000hp pair. Although most of the DRS Class 20/3 fleet is currently stored, it is unlikely that they will all remain idle for too long. Watch this space.

Another company seeking to provide solutions for operators requiring diesel locomotives is UK Rail Leasing, based at the former Leicester TMD. UKRL has a pool of up to 20 Class 56s, three of which are currently passed for main line operation and aims to have a fleet of 8-10 available in due course.

It also provides maintenance, overhaul and ‘spot hire’ services. Its customers have included ROG, Freightliner and Devon & Cornwall Railways (DCR).

In early-2016, UKRL announced that it intended to re-engineer some of its ‘56s’ with modern power units and electronics to create ‘as new’ freight locomotives for around 60% of the cost of a Stadler Class 68 or GE Class 70, with similar performance characteristics to a Class 66 and in a much shorter lead time of around 18 months.

UKRL sees High Speed 2 construction trains as one potential use for the rebuilt Class 56s, as ‘super shunters’ in major yards or as a reserve fleet for Class 66s on intermodal traffic.

Coal traffic collapse

However, since the idea was unveiled a collapse in UK coal traffic has freed many

DB Cargo, Freightliner and GBRf Class 66s for other duties, reducing the need for additional Type 5 diesels. It remains to be seen whether a ‘Super 56’ will ever appear.

A handful of ex-EWS Class 56s are also in use with Colas Railfreight (Nos. 56078/087/094/096, 56105/113, 56302, plus stored 56049/051/074/090) and DCR (Nos. 56311/312).

Small numbers of Class 47s also remain in traffic with West Coast Railway Co, for charter trains, Freightliner, Colas and ROG (see above), although they tend to take a lower profile than many of their ex-BR sisters these days.

After EWS took delivery of 250 Class 66s in 1998-2000, and other freight companies followed suit, the subsequent cull of older diesels led most of us to believe that we’d only see these locomotives from the 1960s and 1970s in action on preserved railways as the 21st century bedded in.

Although they’re fewer in number than they once were, these survivors are proving that there’s plenty of life in the ‘old dogs’ yet – and that, with dedicated engineering support from the likes of HNRC, Brush and LORAM they will still be playing an important role on the modern railway well into the 2020s. ■

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 121 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive