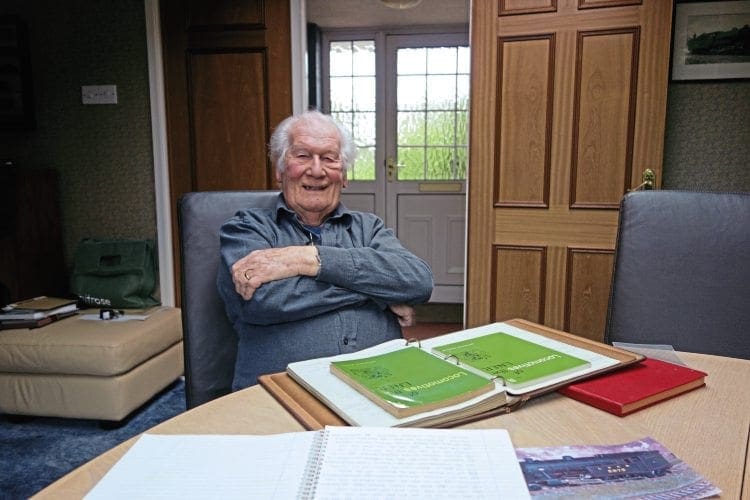

Every self-respecting LNER enthusiast is aware of the RCTS ‘green books’ – the monumental series of volumes describing the company’s entire locomotive fleet. What is not so well known is that the man who made the books possible, series editor Eric Fry, is still with us. On the eve of his 90th birthday, he tells Nick Pigott how the project came about and what it was like to be a wartime spotter in the years before Ian Allan turned the hobby into a national craze.

HOW many of us, while reading, writing or discussing the history of the London & North Eastern Railway, have said: “I’ll just check that in the ‘green books’”? This set of superbly researched volumes entitled Locomotives of the LNER took a remarkable 31 years to complete and covers every detail of the company’s motive power fleet.

The series was published by the Railway Correspondence & Travel Society (RCTS) between 1963 and 1994. It set an extremely high standard for accuracy and enjoys a well-deserved reputation asthe ‘bible’ of the subject.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

Most members of its expert writing team have long since passed away, but the man who had overall control of the project as editor-in-chief is still going strong and is as enthusiastic about railways as ever.

Career

Living in retirement close to the East Coast Main Line in Welwyn, Hertfordshire, Eric Fry was responsible for the editing and co-ordination of this vast undertaking, often joking that it was his career… and that in his spare time he worked as an insurance underwriter for Lloyd’s of London!

Born in Hornsey on May 6, 1927, Eric was initiated into the hobby of engine spotting at the age of seven by his cousin Donald, who was a couple of years older. In those pre-war days, there were no Ian Allan ABC booklets listing every number but, from 1935 onwards, the RCTS began producing national fleet details for the benefit of members and although it was necessary to be a ‘gentleman of at least 16 years of age’ to join the society, the information sometimes filtered down to youngsters on the lineside and so wasn’t quite as dark an art as many people assume it to have been.

There was another reason why Donald and Eric had a head start on other lads of their age. “My aunt Gertrude used to take us on picnic trips to Hadley Wood to watch the trains go by,” recalls Eric.

“One day, in about 1938, we heard from a pal that there was an engine shed at a place called Neasden.

“We hadn’t the faintest idea how to get there, but to our amazement aunt Gertude said she’d take us on the bus. On the appointed day, she wore a long summer frock and carried a parasol and as we walked onto the shed, a fitter stuck his head up from beneath an engine on a pit and was about to tell us boys to “clear off” when he saw this lady in all her finery. ‘Oh sorry, madam’, he blurted and shot back under the loco!”

Remarkable

With an initial experience like that, it was little surprise that E V Fry (to use the form of address that appears in the books) went on to ‘bunk’ every major locomotive depot in the country during the next couple of decades.

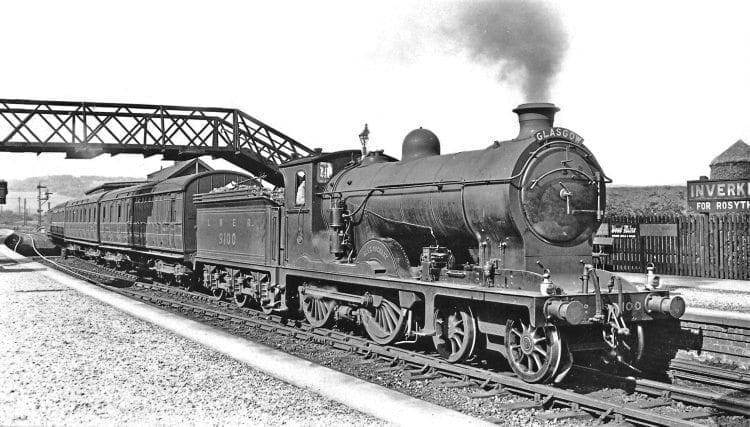

“The remarkable thing is that I copped most of my 7,680 LNER locos during the Second World War, clearing virtually the entire Great Eastern section by regular three-weekly trips to my local shed at Stratford and by using my pocket money and early wages to travel to depots further afield.

“I was only in my early teens when I began making those visits in 1941, but my philosophy was always to treat railways and railwaymen with respect, look as though I knew where I was going and never stop in the open to write numbers down.

“I wasn’t able to acquire official permits as they weren’t issued during the war and I never asked at foremen’s offices because, if I’d travelled hundreds of miles to get there, the risk of a refusal would simply have been too great.

“Despite that, I only failed on a couple of occasions to gain full access to a depot. I recall being challenged once at Eastfield, in Glasgow, but even then the shedmaster relented once he realised I’d travelled all the way from London.

“Most officials were very friendly, but given the enormous number of times I visited the London area sheds you might have expected me to have been apprehended on the law of averages. Stratford was a particularly special place for me… I went round that huge works and depot complex every couple of weeks, year after year, and was never once stopped.”

Anyone wondering how on earth Eric managed to pull off such remarkable feats must bear in mind that his exploits pre-dated the mass trainspotting craze that swept the nation after the war, so staff and workers would not have been conditioned or instructed to look out for such youths and would simply have assumed him to be a young cleaner or fireman going on or off duty.

Assured

“As I got a bit older and smarter-dressed, some of the workers even mistook me for one of the gaffers,” he smiled. “I once turned up at the Southern Railway’s Dorchester depot to find three men lolling about smoking. ‘Good morning’, I said in an assured manner and they immediately snapped back to attention and began shovelling ash again!”

Hard though it is to believe from a present-day viewpoint, Eric had to undertake most of his mammoth task without the benefit of the BR national shed code system, which wasn’t introduced until 1950.

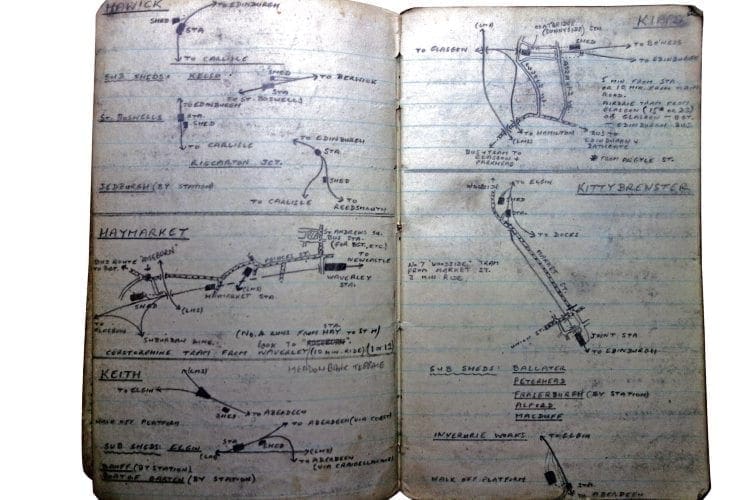

His adventures also pre-date publication of the British Locomotive Shed Directory and he therefore had to find his own way to each depot, some of the inner city ones being hidden among labyrinthine mazes of terraced streets and track complexes.

To help him on future visits, he began compiling his own directions to each location, sketching maps, diagrams, street names and bus and tram routes in a little pocket book – effectively the world’s first such directory. It wasn’t until late-1947 that commercial versions began to be produced by Flt/Lt Aidan Fuller, R S Grimsley and, from 1956 onwards, Ian Allan.

Bombing

At home, Eric entered the hundreds of engines he saw on each of his travels into ring-binder books, transferring them neatly from the notepads he carried in his jacket.

“I didn’t have a lot of money in those days, but I was able to undertake such long journeys because I didn’t smoke or drink and instead saved every spare penny to buy train tickets,” he told me. “I also had parents who didn’t mind what I was doing – when I was about 14 at the height of the war, for instance, they’d taken me to Oxford for a few days to escape the London bombing, but were quite relaxed about me going off by train on one of those days to try to find the LNER’s Woodford Halse depot.

“Trips like that were easier once I’d started work, of course, but it wasn’t a lot of fun travelling in the immensely overcrowded trains of the period, especially when there were black-outs, and I often had to spend entire journeys standing with soldiers and other passengers in packed corridors.

“When you consider the conditions, it’s remarkable how relatively freely I was able to move about by foot and public transport. On one notable occasion in the Scottish lowlands industrial belt, I managed to locate and bunk no fewer than 25 different sheds and sub-sheds in a single day even though some took me a long time to find.”

‘Sitting duck’

Eric had left school in 1943 but was denied the opportunity to fight for his country after failing his medical. Instead he’d sought a job on the railways and duly went for an interview at Stratford Works, but his father wasn’t keen on the idea and persuaded him to take a position with Lloyd’s of London as a trainee insurance underwriter. “You did what your dad told you in those days!

“I earned ten bob a week and commuted on the Loughton line from our family home in Woodford. That was pretty hairy – the carriages were wooden-bodied and on one occasion the train I was travelling in was halted high on a viaduct when suddenly the air-raid sirens began to wail. I felt like a sitting duck!”

Apart from scary moments like that, the ’40s were a fascinating time for Eric, who had no idea that the hobby he and a relative handful of other people were pursuing would later be taken up by hundreds of thousands of youngsters in the British Railways era. In fact, he says he only bought the first Ian Allan numbers booklet in 1942 out of curiosity to see if there were any errors in it. “There were, but mainly only in the sub-class sections.”

Ian Allan somehow managed to continue publishing during the hostilities, but the national manpower and paper shortages, coupled with the wartime omission of loco stock returns in the annual reports of the Big Four companies, resulted in a cessation of RCTS stock lists until 1946.

By the time the BR era arrived on the scene two years later, Eric had virtually ‘cleared’ the London & North Eastern Railway (although LNER-design engines were still being built) and was making deep inroads into the fleets of the former LMS, GWR and SR. His final LNE design loco – 1950-built ‘B1’ No. 61369 – proved elusive but was finally copped at Leicester GC shed in September 1955 to give him 7,545 steam locos, 68 electrics, 60 railcars and seven internal combustion machines.

He didn’t quite complete the other three quests, however, as marriage to sweetheart Helen came along in 1957 after a three-year romance – “and married life wasn’t compatible with long weekend shed-bashes”, he laughed.

Instead, his railway interest was pursued in a different way. “I had joined the RCTS the minute I was allowed to on my 16th birthday and my youthful enthusiasm soon got me noticed by the stock list compilers, who roped me in as an assistant editor.

“A couple of years before I’d joined, the society had published a book entitled The Locomotives of the LNER 1923-1937, by K Risdon Prentice and Peter Proud, based on articles that had appeared in its journal, the Railway Observer. After the war, Mr Proud was planning to update that work and the RCTS was also in the process of publishing a multiple-part Locomotives of the GWR series, the first volumes of which appeared in the early 1950s.

“I rather rashly made the suggestion that we do a similarly enlarged series for the LNER,” said Eric, “but although everyone agreed it was a good idea, they ‘volunteered’ me to take responsibility so I had to set about finding an editorial team. The GW series was marvellous but I considered it to be a bit soulless.

Qualities

“For example, as a reader I didn’t just want to know how many locos had received modifications, but why. I also wanted to bring the engines to life by describing something of their individual achievements, allocation changes and traffic uses. I therefore resolved to bring those qualities to the LNER books.”

Mr Proud agreed to join the editorial team rather than press ahead with a revision of his own book and the other specialists Eric persuaded to come on board included Dr Ian C Allen, Ken Hoole, Willie Yeadon, Maurice Boddy, Eric Neve and W A Brown, each an acknowledged expert in his own field.

The Great Eastern class sections were researched and written by Mr Fry himself, his numerous Stratford visits over the years standing him in good stead in that regard. He also managed to assemble a pool of volunteer typists to transcribe the handwritten manuscripts and arranged for batches of carbon copies to be taken of every page for circulation among the authors, Railway Observer editors and other knowledgeable historians for checking.

The series was originally intended to comprise 10 books – a preliminary survey followed by five volumes on tender engines, three on tank engines and one detailing miscellaneous locos, railcars and statistics – but after permission was granted for official railway records not previously available to be examined, the resulting embarrassment of riches resulted in a radical re-assessment and in the end no fewer than 19 books were produced (see panel).

It took 31 years to publish them all, but the whole project actually took 40 years from start to finish – 1954 to 1994 – and covered every one of the 10,000 or so locos owned by the LNER at one time or another between January 1923 and December 1947.

“I’m often asked where we obtained such full and accurate information,” says Eric. “In that respect, we had two huge strokes of good fortune. Firstly, the chief mechanical engineer at Doncaster in the 1950s, Kenneth Cook, had previously worked at Swindon and was highly impressed by the GWR books the RCTS was producing. When I told him we were planning an LNER version, he wrote to all his works managers at Doncaster, Darlington, Gorton, Stratford, Cowlairs and Inverurie instructing them to give us free and unfettered access to all their records.

Gum tree

“Secondly, many of the Stratford records had been lost in a flood some years earlier and I was both surprised and dismayed when the works manager told me the only thing his office was able to use for reference was Peter Proud’s original RCTS book! However, I decided to go and see the erecting shop foreman and after hearing that I was up a gum-tree with regard to research, he produced from a cupboard a huge leather-bound volume detailing every engine that had been through the shops since 1872!

“‘The works manager doesn’t know we’ve got this’, he said with a wink. ‘We’ve just kept it going for our own use’.

“That book was a godsend; I was eventually allowed to keep it and today it is in the care of the Great Eastern Railway Society.”

Eric and his team set out to produce what they hoped would be finality in terms of statistics and dimensions and in that regard they succeeded beyond their wildest dreams.

Obviously, there would be personal reminiscences and arcane facts known only to certain ex-railwaymen that would come to light afterwards, but apart from Part 11, which contained updates and supplementary details, Eric takes great pride in the fact that there has never been a need for major revision of any of the volumes. “I was fortunate in having an extremely knowledgeable team to support me and I can honestly say that there was never a cross word exchanged between any of us in all those years.”

Some of the 2,000 or so photos contained in the series were taken by him on a Leica camera he’d treated himself to in May 1946, a few months after wartime film and photography restrictions were lifted. “I deliberately chose that type of camera as it was of higher quality than a box Brownie yet small enough to slip easily into my pocket during unofficial shed visits,” he explained. “That way I didn’t draw attention to myself as I would have done with one of the large plate cameras and tripods used by many other railway photographers of the time.”

The books are renowned for their rare illustrations and to give an idea of how hard Eric and his colleagues had to work in that regard, Part 2A alone (which features the Pacific tender classes) contains no fewer than 275 photographs drawn from 58 different sources.

In the mid-1960s, Eric encountered something of a mid-life crisis and left Lloyd’s to join one of those sources – Photomatic, a leading supplier of transport postcard prints to enthusiasts. He stayed there only four years, realising he had made a mistake and returning in 1969 to his former employer, with whom he remained until calling it a day at the age of 63 in 1990.

Retirement

Even in retirement, there was to be no escape from railway research, though. That year, one of the leading members of his editorial team, Willie Yeadon, began publishing a magnum opus of his own – a 50-volume Register of LNER Locomotives listing many of the details there had simply been no space to include in the RCTS series, namely the individual shed allocation dates, works shopping dates, boiler and tender numbers and withdrawal details of every single engine.

“It was a project Willie had been working on for more than half a century and included hundreds of previously unpublished photos illustrating the details in the text, but after just 13 volumes, he had the misfortune to die,” said Eric.

“So I volunteered my services as a proof-reader to the publishers and from 1998 until the final volume in 2011, I worked on Willie’s draft manuscripts to ensure the books were produced to the standard he would have expected.”

With that second monumental project behind him, Eric is now free to concentrate on his other great love, scale modelling, and he enjoys visiting his local model railway club at least twice a week.

To today’s young railfans, his memories must seem almost prehistoric.

He saw the original ‘P2’ class 2-8-2 No. 2001 Cock o’ the North on display at Stratford and another memorable sight was of pioneer Gresley Pacific No. 4470 Great Northern in the process of being rebuilt into an ‘A1/1’ at Doncaster in 1945. “I wasn’t impressed by Edward Thompson’s choice of that particular engine for rebuilding, especially as his Pacifics were such a hopeless and ungainly lot,” said Eric, “but I suppose, in his own mind, it was logical to start with the first of the class.”

‘Rare cops’

Fortunately, Thompson didn’t attempt to butcher the ‘A4s’, whose impressive streamlined profiles Eric remembers seeing streak past on ‘The Coronation’ and other expresses during the pre-war picnics he enjoyed at Hadley Wood with aunt Gertrude. Proving that glamorous machines aren’t the be-all and end-all for genuine enthusiasts, he also recalls the thrill he felt when unexpectedly stumbling upon a LNER railmotor dump in a suburb of Darlington. “That was a wonderful day for rare cops,” he smiled.

A large proportion of the locos this master spotter saw were withdrawn before many readers of The Railway Magazine were even born, and although the rail industry is not nearly as extensive or varied as it was in the 1940s and ’50s, it has continued to provide interest and fascination for younger generations. Today, Eric keeps in touch with this ever-changing scene through society memberships, magazines and regular phone chats with fellow veterans.

One of the biggest changes in the hobby in recent years is, of course, the ability of modern spotters to find out via mobile phones and the internet where their wanted locos and units are likely to be at any given time, but Eric – who like many of his generation “can’t be doing” with emails and suchlike – feels that advance knowledge takes much of the challenge out of the hunt.

“It certainly would have been much easier if I’d had such aids but there wouldn’t have been the same exciting sense of discovery and satisfaction. It was a lot more fun the way I did it!” ■

The Railway Magazine Archive

Access to The Railway Magazine digital archive online, on your computer, tablet, and smartphone. The archive is now complete – with 122 years of back issues available, that’s 140,000 pages of your favourite rail news magazine.

The archive is available to subscribers of The Railway Magazine, and can be purchased as an add-on for just £24 per year. Existing subscribers should click the Add Archive button above, or call 01507 529529 – you will need your subscription details to hand. Follow @railwayarchive on Twitter.