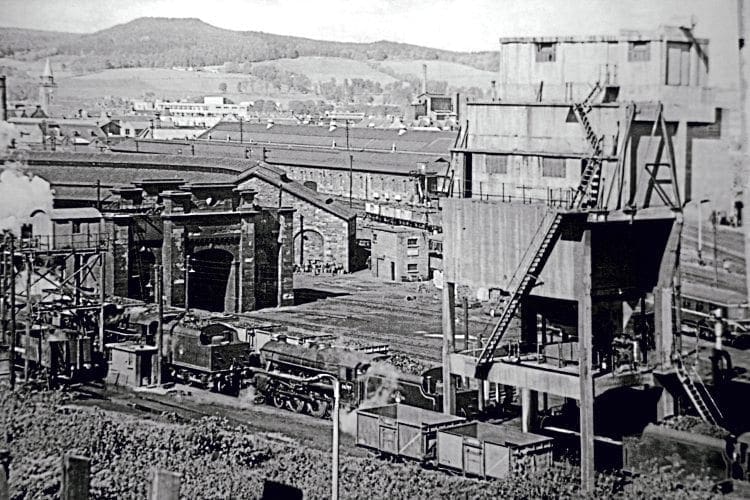

The demolition of Immingham’s mechanical coaling plant last year has left Britain with just one example of these huge ferro-concrete monoliths.

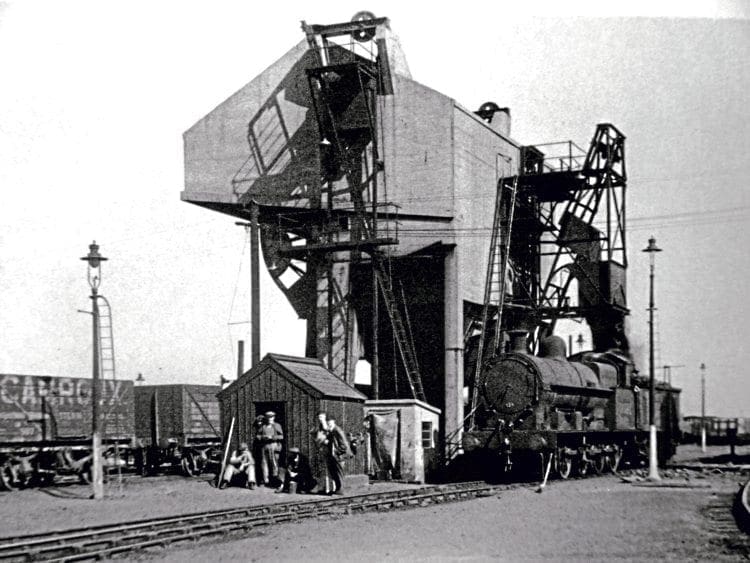

Engine Shed Society president Nick Pigott concludes our historical survey of the towering landmarks that once dominated the scene at more than 100 steam depots. Whether wagon-hoist or skip-hoist forms of operation were preferable for ferro-concrete coaling towers was a debate that occupied engineers for a considerable time.

The wagon versions used large amounts of electricity in bodily lifting heavy weights to heights of 60ft or more and it was often found cheaper to empty the wagon into a tippler at ground level and raise a skip instead, even if that container held as much as 20 tons. The skip method also had the advantage that the operator didn’t have to climb by ladder to the top of the tower should a wagon need inspecting to ensure its contents had fully emptied.

Monthly Subscription: Enjoy more Railway Magazine reading each month with free delivery to you door, and access to over 100 years in the archive, all for just £5.35 per month.

Click here to subscribe & save

With a ground-level tippler, it was also easier if large foreign objects, such as loose timber wagon planks or metal bars, had accidentally found their way into a main line wagon, perhaps at a colliery, for they would jam the mechanism at ground level and could thus be more safely removed.

There was also a lower risk of small objects falling out unnoticed and ending up buried in a loco’s tender if the contents of full wagons were not first inspected (which was impractical of course). In one celebrated incident at Doncaster in the 1940s, a wagon containing loaded oil drums was tipped into the top of the tower by an unsuspecting operator.

When the next load of coal was dropped, the drums burst, sending hundreds of gallons of sticky liquid into the 40ft deep hopper and putting the plant out of action until it was cleaned up. Even in day-to-day operation, there was a tendency for small amounts of lubricating oil to leak out of axleboxes while the wagons were inverted. At some depots, this was considered too valuable to waste and gutters and barrels were fitted at the base of the hopper to catch it, but a lot of oil was simply lost or burnt in fireboxes.

The important job of ensuring the correct grade of coal entered the correct hopper was easier with a skip-hoist type, too. Different grades of coal could be accurately targeted towards their respective hoppers by an electric traverser at the top of the tower, whereas with a wagon-hoist, care had to be taken to ensure the correct hopper compartment valve was open before the wagon was emptied.